New development expected to arrest European offshore decline

Matt Cook

Douglas-Westwood

London

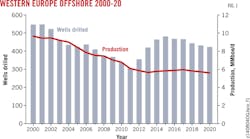

After playing a pivotal role in the European economy for decades, offshore hydrocarbon production has declined steeply in recent years and is struggling to arrest the dive. Since 2000, offshore oil and gas output has fallen 41% to 5.6 MMboe/d in 2013 from 9.7 MMboe/d (Fig. 1).

The decline is largely the result of outdated regulation, aging infrastructure, and depleted fields. Well completions during 2000-13 have dropped at about half the rate of production, suggesting more greenfield projects are desperately needed as average well flow rates plummet.

For this to happen, however, exploration activity must increase. This is particularly the case in the UK, which has seen the most dramatic production decline since the peak in the late 1990s.

Dated regulation

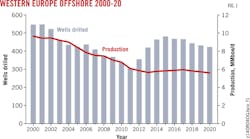

Offshore oil production in the UK has plummeted since 2000 with 2012 output equaling 35% of 2000 levels. This cannot be put down to the UK Continental Shelf's (UKCS) extreme maturity alone (Fig. 2).

Outdated regulation also has played a part. When the UK's offshore production regulations were drawn up in the 1970s, developments were confined to the largest UKCS fields. Such fields allowed for high taxes and single-minded infrastructure due to the geographical spacing of projects.

Of the 300 fields now producing offshore UK, many are relatively small and unsuitable for tax regimes devised for large fields. Ideally, such small fields would be served by infrastructure developed by several operators for multiple projects-currently this is not encouraged by the UK Treasury or the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC).

The recent Wood Review highlighted the significance of these problems and suggested field allowances be addressed project by project with collaboration among operators to produce more effective, less costly infrastructure (OGJ Online, Feb. 4, 2014).

Continued investment

Despite the decline, investment in the UKCS has remained high-£14 billion ($23.5 billion) was spent in 2013, £10 billion more than in 2000.

This was partly due to the high costs associated with the region but also as a result of redevelopments of old assets and downstream infrastructure upgrades, such as BP PLC's Sullom Voe oil terminal and Total SA's nearby greenfield gas terminal (OGJ Online, Oct. 8, 2013).

Douglas-Westwood's (DW) new "World Development Drilling and Production Market Forecast 2004-2020" predicts UK offshore oil well completions will climb to 126 by 2017, up 14% from 2013. Gas well completions also will jump by 12% to 86 in 2017 from 2013 (75 completions).

This increase is due to the number of new enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations in mature fields as well as a shift towards such deepwater projects as Total SA's Laggan gas field in the West of Shetland area.

The rallying of annual well completions will likely translate into an arrest of the production decline seen during the previous decade. Oil and gas production should reach a secondary peak of 1 million b/d and 0.7 MMboe/d in 2017, up 16% and 3%, respectively, compared with 2013. Such relatively small gains highlight the struggle faced by the UKCS to maintain output and how quickly reforms are needed to safeguard long-term offshore production.

Increasing production, onshore competition

Implementation of the Wood Review's recommendations could lead to a combined production of about 2 MMboe/d by 2017 (as suggested by Oil & Gas UK). This translates into 300 wells/year drilled offshore in 2017, about 41% more than the DW base case.

This number would probably be sustained into the next decade. Further adding to the likelihood of this high case is the current situation in Ukraine. Should the conflict between Ukranian government forces and pro-Russian separatists continue, gas supplies may be greatly reduced. The UK currently imports 15% of its total gas supply from Russia.

Another threat to offshore operations could be increased competition from the UK's onshore unconventional plays. Northwest England currently has small-scale shale gas operations with exploration wells yielding promising preliminary results. As with many European countries, however, hydraulic fracturing faces some public opposition over fears of potential groundwater contamination.

Despite this, Westminster remains optimistic large-scale production is possible and is actively encouraging operators to explore across the country. Positive signs came with Total's farm in to blocks in eastern UK, but the major pledged just £12 million to exploration activities.

Norway production

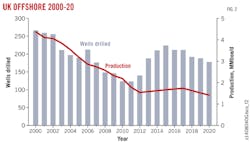

Since the end of the 20th century, Norway's oil output has experienced a fate similar to that of the UK, albeit not as severe. Oil production has fallen by half to 1.5 million b/d in 2013 from 3.1 million b/d in 2000 (Fig. 3).

Gas, however, has gone from strength to strength. In 2013, output stood at 1.8 MMboe/d, a 214% increase over 2000 levels. Extremely successful exploration off Norway doubled gas reserves 2000-06. Gas production will be maintained around the 1.9 MMboe/d mark, making it the only North Sea country to avoid gas production decline.

Ongoing field development

Sustained gas production hinges on certain key projects. Troll field holds about 40% of the Norwegian Continental Shelf's (NCS) gas reserves as well as an estimated 2 billion bbl of oil. Long-term success hinges on this deposit continuing to be prolific.

There are positive signs in this regard. In recent years, additional drilling of development wells has maintained production in the field and French seismic company CGG is to conduct one of the area's largest-ever shoots.

As well as Troll, Ormen Lange will be pivotal to Norway's future gas production. On stream since 2007, the giant gas deposit has 1.4 billion boe still in place. Rising operating costs, however, threaten future production-Royal Dutch Shell PLC's subsea compression project for the field was recently cancelled due to the operator's dim view on its economic return. The company insists, however, that long-term production will be largely unaffected. Troll and Ormen Lange accounted for nearly half of Norwegian gas production in 2013, just short of 1 MMboe/d.

It is not all easy going for Norwegian projects, however. The two prolific fields referred to above must be developed in tandem with greenfield projects, and two of these large developments are currently experiencing setbacks.

The Goliat floating production, storage, and offloading vessel, expected to contribute heavily to Norway's sustained output, has yet to be completed (see cover). The platform's operator, Eni SPA, insists the FPSO will begin operating in the Barents Sea field this year, but it is rumored the floater could require millions of additional man-hours to finish in compliance with Norwegian regulations. Whenever first production may be, Goliat is set to contribute as much as 4% of Norway's total hydrocarbon output over the next decade.

The Johan Sverdrup concept also is facing difficulties (OGJ Online, June 30, 2014). Discovered in 2010, the expansive field was appraised at an upper limit of 3.3 billion boe of recoverable resources. Despite an estimated output of 0.6 MMboe/d by 2019, Statoil ASA seems reluctant to commit to the current green onshore power solution for the project, citing high costs as the problem.

Even with the delays mentioned, the abundance of projects off of Norway will see well completions rise past 200 in 2016 and likely stay there into the 2020s. Oil well completions will rally slightly before the end of the decade, up 16% by 2020 from 83 in 2013. The increase in the number of gas projects and reserves also will see gas well completions climb to 112 from 97 in 2013, an increase of 15%.

Netherlands decline

Behind Norway and the UK, the Netherlands is Europe's third largest offshore gas producer-2013 output was 0.4 MMboe/d. Falling offshore reserves, due to a lack of discoveries, has seen production decline to 71% from 2000 levels. As a result, the number of wells drilled off the Netherlands should fall to four in 2020 from six in 2013.

Large investment in exploration is unlikely due to the Dutch government's commitment to shift to a greener energy mix with nuclear power generation receiving the most focus. Indeed the government has conceded the Netherlands will become a net importer of gas by 2025.

A further problem for Dutch offshore production is the abundance of onshore reserves. Due to high well flow rates, the country saw seven gas wells drilled in 2013 to maintain production at 0.9 MMboe/d.

Shale gas extraction remains a possibility, but recent tremors in the Groningen area may dissuade the public from the concept. The small earthquakes also prompted the Dutch government to cut production from the field by 15-20%; could offshore gas developments fill this gap?

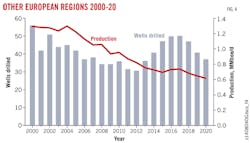

Other European regions

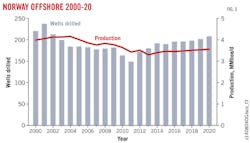

Italy has several offshore projects currently operating or being developed. Aquila oil field, estimated to hold 20 million bbl of oil, is currently producing via a tanker-derived FPSO. The field has yielded an estimated 20,000 bo/d since 1998 (Fig. 4).

Discoveries off Sicily have increased reserves in recent years and could lead to offshore output peaking at 0.4 MMboe/d in 2018, necessitating around 80 wells to be drilled in the interim. This will be an increase on recent years due to a reduction in drilling activities following the Gulf of Mexico Macondo well blowout and oil spill (OGJ Online, Feb. 21, 2013). As with the UK, this scenario would be affirmed by ebb in Russia's gas supplies, which accounted for 42% of total Italian imports in 2013.

Despite being a small entity in the North Sea, compared with Norway and the UK, Denmark is the EU's only net exporter of oil; its first offshore oil discovery was in 1965 (OGJ, Sept. 5, 1966, p. 105).

Despite its exporter status, the country is now dogged by mature fields. Implementation of EOR will arrest the decline seen in output since 2004: Hydrocarbon production has dropped to 0.25 MMboe/d in 2013 from 0.6 MMboe/d. As well as EOR, Hejre field (due on stream in 2015) contributes to production rallying to 0.3 MMboe/d in 2017. This increase will require more wells drilled for the small number of producing fields. Well completions will peak at 26 in 2016, up from nine in 2013.

The author

Matt Cook ([email protected]) is an analyst at Douglas-Westwood, Faversham, UK. He holds a BS in geology from Imperial College's Royal School of Mines.