Texas Supreme Court rules on post-production costs, royalty payments

Stephan D. Selinidis

Reed Smith LLP

Houston

Producers calculate oil and gas royalties using a relatively straight-forward formula, but litigation can still arise from any of its variables. The royalty payment equals the royalty owner's net interest multiplied by the total value of production from a well minus the royalty owner's share of post-production expenses. It is becoming more common in Texas for royalty owners to contest post-production expenses.

Royalty owners specifically are claiming that operators improperly categorize an expense as post-production when it is a production expense. Royalty owners might also claim a lease or other agreement provides that royalty interest is free of post-production expenses.

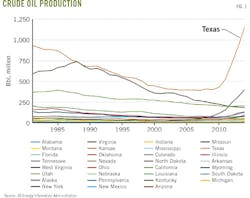

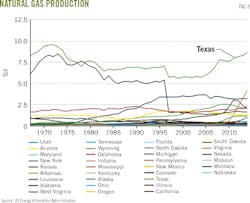

Texas is among the highest producing oil and natural gas states (Figs. 1-2). Post-production expenses involve millions of dollars in allocations between working-interest holders and royalty owners.

Operators must ensure that post-production expenses comply with Texas laws and lease terms. This article provides an overview of general Texas law regarding royalties and the allocation of production and post-production expenses. It will discuss the Texas Supreme Court's opinion in French vs. Occidental Permian Ltd., in which the issue was whether carbon dioxide extraction from casinghead gas during a tertiary recovery operation was a production or post-production expense.

It will also discuss the Texas Supreme Court's opinion in Chesapeake Exploration LLC vs. Hyder, in which the court analyzed post-production expense allocations for a "cost-free (except only its portion of production taxes) overriding royalty."

Texas courts define a royalty as a share of production free of production expenses but subject to post-production costs. Overriding royalties are carved out of the working interest and are generally free of production expenses. But overriding royalty owners are subject to proportional post-production costs. The parties, however, may agree to alter these general definitions.

Texas courts apply a plain-terms analysis to oil and gas leases. An oil and gas lease is interpreted as any other contract. In construing an unambiguous lease, courts seek the parties' intent. Courts apply plain, grammatical meaning to lease language unless doing so clearly defeats the parties' intentions.

One problem with analyzing post-production expenses in Texas is the terminology. Industry and Texas law generally categorize expenses borne solely by the working interest as production expenses. Post-production expenses are expenses shared between the working-interest holders and royalty owners.

Royalty provisions for decades stated that royalties were to be paid at the well where production ended. Many leases, however, now provide that royalties will be paid on oil or gas delivered into tanks or pipelines, at a plant's tailgate, at the point of sale, or other locations.

Texas law uses the designated delivery point in the parties' lease to determine the allocation of expenses between the working and royalty interests. Lease language is more important than the fact that production ends at the wellhead.

The working interest holder is solely responsible for the cost of getting oil or gas to the delivery point, whether it's the wellhead, the tank, the pipeline, the tailgate of a plant, the point of sale to a nonaffiliated third party, or some other point.

Subsequent expenses adding value to the production can be shared proportionally between the working and royalty interests. An expense can occur post-production from an operational standpoint but be treated as a production expense from a royalty-accounting standpoint.

This article used production and post-production terminology for categorizing expenses that might or might not be shared with the royalty interest because those are the words industry and the Texas courts use.

It's impossible to broadly state what costs always are borne solely by the working interest or always may be shared between the working and royalty interests. Terms of a lease, the nature of the expense in question, and the precise character of the royalty provide case-by-case answers.

Working-interest holders generally pay all production costs, defined as the expenses incurred in exploring for hydrocarbons and bringing them to the surface. These costs include:

• Geophysical surveys.

• Drilling.

• Tangible and intangible costs incurred in testing, completing, or reworking a well.

• Secondary or tertiary recovery.

Production is defined as extracting oil or gas from the well for storing or selling, meaning production ends at the wellhead.

It would follow that post-production begins after the wellhead. Post-production costs, which generally are shared proportionally between the working and royalty interests, include:

• Gross production and severance taxes.

• Gathering.

• Transportation.

• Treatment required to make the hydrocarbon fit to be sold, such as dehydration, the removal of CO2 and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), compression to make gas deliverable into a pipeline, and manufacturing costs incurred in extracting liquids from gas or casing-head gas.

But the line between production and post-production is not always clear, particularly during tertiary recovery operations.

French vs. Occidental Permian

The issue in French vs. Occidental Permian Ltd. was whether the expense to remove CO2 from casinghead gas during a tertiary recovery operation was a production expense or a post-production expense.

Oxy operated the Cogdell Canyon Reef Unit (CCRU) in Scurry and Kent counties, Tex. CCRU casinghead gas contained less than 2% CO2.

The Fuller gasoline plant processed casinghead gas to remove H2S and nitrogen, both contaminants, and to extract natural gas liquids (NGLs).

In 2001, Oxy began injecting CO2 into the CCRU. Oil production rose to 5,800 b/d compared with 1,500 b/d during the late 1990s. Without the CO2 flood, production would have declined to 200 b/d and become uneconomical, stranding more than half of the oil in place.

After CO2 injection began, CCRU casinghead gas contained 85% CO2. That percentage was too high to be processed at the Fuller gasoline plant so Oxy hired Kinder Morgan Co. (KM), which removed at least 90% of the CO2 and most of the H2S from the casinghead gas for reinjection.

KM extracted 66% of total NGLs for sale. KM contracted with Torch Energy Marketing to remove the remaining CO2 and H2S at the Snyder gasoline plant. Remaining NGLs also were extracted.

Oxy paid KM a monthly fee of $0.33/Mcf delivered to KM's plant plus 30% of the total NGLs in-kind and 100% of the residual gas at the Snyder gasoline plant tailgate. In calculating royalties on casinghead gas, Oxy considered 70% of the NGLs provided by KM.

Oxy did not pay royalties on the remaining NGLs or any of the residual gas paid to KM. Oxy, however, did not charge royalty interest on any part of the $0.33/Mcf fee.

Oxy treated 30% of the NGLs and 100% of the residual gas as a post-production expense to prepare casinghead gas for sale. Oxy allocated that expense between working and royalty interests. The monthly $0.33/Mcf fee on gas delivered was considered a production expense and paid solely by Oxy, the working-interest owner.

The royalty owners sued Oxy for underpayment of royalties, alleging "the transportation of the casinghead gas from its gathering point to the [KM] plant some 15 miles away, the processing at the [KM] plant, the transportation of the partially processed streams of NGLs and gas to the Snyder [gasoline plant], the removal of CO2 there, and the transportation of...CO2 and H2S from both plants back to the injection wells," were production expenses.

Royalty owners said any NGLs that KM extracted were incidental byproducts of removing the CO2 and part of the production process. They wanted the royalty to be based on the value of 100% of the NGLs net extraction expenses and removing H2S, plus the value of 100% of residue gas.

Oxy maintained that CO2 removal was necessary to sell the casinghead gas so it was a post-production expense that royalty owners should help pay. The producer also described 30% of the NGLs and 100% of residual gas paid KM as compensation for post-production activities, for which no royalty was due because the royalty interest must bear its proportionate share.

The Texas Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the cost to separate injected CO2 from casinghead gas was a post-production expense that could be charged proportionately to royalty owners.

The court initially recognized that royalty provisions were based on market value at the well and the proceeds from the sale of casinghead-gas products net of post-production expenses. But instead of analyzing these common and well-understood royalty clauses, the court undertook a fact-specific analysis, ruling that CO2 separation was a post-production expense because:

• Unlike separation of oil from water for the water flood, CO2 separation from the casinghead gas was not critical to continued oil production.

• The entire casinghead gas stream could have been reinjected into the formation without any processing. That stream was 85% CO2 and included NGLs and residual gas.

• The CCRU agreement stated no royalties would be due on casinghead gas reinjected into the formation.

• Agreement terms gave Oxy sole discretion on whether to reinject or process the casinghead gas.

• The royalty owners benefited from Oxy's decision to process the casinghead gas.

The royalty owners must share the cost of CO2 removal in these circumstances because the royalty interest owners gave Oxy the right and discretion to decide whether to reinject or process the casinghead gas and because they benefitted from Oxy's decision to process and sell the gas.

The court said the cost of separating injected CO2 from the casinghead gas was a post-production expense to be paid proportionately by the working-interest holders and royalty owners. But this ruling was fact specific, leaving working-interest owners susceptible to royalty owner claims that the cost of separating injected CO2 is a production expense to be borne solely by the working-interest holders.

Chesapeake Exploration vs. Hyder

An overriding royalty on oil and gas production is free of production costs but must bear its share of post-production costs unless the parties agree otherwise. The issue in Chesapeake Exploration LLC vs. Hyder was whether the lessee agreed to pay for all post-production expenses relating to an overriding royalty.

The overriding royalty provision provided for "a perpetual, cost-free (except only its proportion of production taxes) overriding royalty of 5% of gross production obtained" from directional wells drilled on the lease, but reaching TD on nearby land.

The lease provided each lessor the "continuing right and option to take its royalty share in kind," although no lessor exercised that right. The parties did not dispute that the royalty can be paid in cash.

Chesapeake drilled seven directional wells on the leased premises that produced from land not subject to the lease. Chesapeake paid royalties on production from those wells after deducting gathering, transportation, and a 3% marketing fee as post-production costs.

The royalty owners argued that the cost-free language in the overriding royalty provision constituted an agreement that Chesapeake would pay all post-production expenses, including any gathering, transportation, or marketing fees.

But Chesapeake asserted that cost-free language merely emphasized that the overriding royalty was free of production costs and did not relate to the allocation of post-production expenses.

The Texas Supreme Court sided with the royalty owners, ruling that the cost-free language frees the overriding royalty from post-production expenses. The court concluded a production-taxes exception indicated that cost-free language applied to post-production expenses. Taxes are considered a post-production expense.

"It would make no sense to state that the royalty is free of production costs, except for post-production taxes (no dogs allowed, except for cats)," the court said, asking Chesapeake to show why cost-free language cannot refer to post-production costs. Chesapeake argued that a royalty paid on gross production must be measured at the wellhead and, therefore, is the same as a royalty paid at the well, which bears post-production costs. The court said a requirement to measure wellhead volumes does not indicate whether the overriding royalty must bear post-production costs.

The royalty-pricing mechanism drove post-production expenses, judges said. For example, the oil royalty in the same lease bore its share of post-production expenses because it priced oil based on market value at the well, not because the oil volume was measured at the wellhead.

Similarly, the gas royalty in the same lease was free from the burden of post-production expenses because it priced gas based on the price received by Chesapeake's affiliate after post-production costs were paid, not because the gas volume was measured away from the wellhead.

Chesapeake argued overriding royalty value should be equal whether the royalty is paid in cash or in kind, assuming that royalty owners incur post-production costs if the gas was taken in kind. The court countered that royalty owners taking gas in kind does not suggest the overriding royalty must be subject to those costs when taken in cash. Consequently, the court said cost-free language in the overriding royalty provision includes post-production expenses.

Practical implications

In French and Hyder, the Texas Supreme Court left working interest-holders vulnerable to future underpayment of royalty claims based on post-production expense allocations. Companies assessing expenses to extract CO2 from casinghead gas might:

• Review how CO2 extraction fits within overall enhanced oil recovery operations. Is the CO2 separation from the casinghead-gas stream necessary for production?

• Review whether, under the applicable leases and unit agreement, the operator can reinject the entire casinghead gas stream without paying royalties.

• Review whether, operationally, the casinghead-gas stream can be 100% reinjected without processing.

• Compare the cost allocated to the royalty interest for separating CO2 from casinghead gas to the gas-sales benefit royalty owners receive.

Working-interest owners should review lease royalty provisions and overriding royalty terms to assess liability for any cost-free language. Producers should review how post-production expenses have been allocated and whether that complies with the Hyder ruling.

The author