Financing new E&P technology ventures

SIDDHARTH MISRA, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS, AUSTIN

Editor's Note: This is the second in a two-part series. Part 1 appeared in the June 2015 issue of OGFJ. This article picks up detailing financing sources.

Sources of New Venture financing

Venture leasing

In a venture leasing scenario, all leases offered to new ventures are subject to considerable risks. A lessor's return is generally tied to financial performance of the venture, so that, when a venture does well, the lessor realizes more of return, thereby, reducing the risks involved. For a new venture, leasing has tax advantages compared to owning. If the venture opts to purchase rather than lease, the firm might not have sufficient income to realize the tax benefits of recording depreciation expenses.

Customer financing

Customer financing is a direct loan or a down payment for a future order. The customer is a value-added investor. Such financing can be a double-edged sword because the customer knows more about the company once he is an investor. Additional customer insight makes it tough for a supplier to increase price as the customer is aware of the price of the product.

Corporate venturing

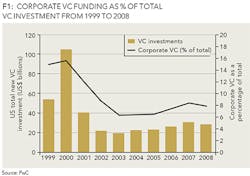

A corporation becomes a financing source for many new ventures through an R&D budget, internally managed venture investing, or externally managed venture investing. A corporation involves itself in order to capitalize on opportunities of high return, to develop its product market strategy, or to build a strategic partnership by direct investment. Comcast, for example, established a $125 million fund to invest in companies in order to capitalize on Internet advances for broadcasting purposes. Mostly, corporations invest in companies with products and services related to their industries, and generally, such investments are considered part of a corporation's R&D activity. But during economic hardships, venture capital funding is pulled back as it is not the primary objective of the corporation. (See Fig.1.)

Government programs

Financing can also be obtained from government-supported programs aimed at providing loans and other financing for start-ups, small firms, firms with growth potential, and to support R&D. In 1983, the Small Business Administration (SBA) was set up to provide facility of guaranteeing of loans made by banks and other financial institutions. In 2008, SBA arranged and guaranteed $18 billion in new loans. As an enterprise matures, an entrepreneur is able to raise capital in the form of debt. At that stage, SBA's Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) finances a venture's investment needs. SBIC-financing is more like an interest bearing loan that is guaranteed by SBA and, recently, like a loan that includes warrants where total return is tied to the venture's success. One example is SBIC's investment in Cray Research and Federal Express.

Trade credit

This source of financing is important when risk capital is scarce (in emerging economies, for example). Simply, the supplier provides the venture with a zero-interest loan for a certain period. The trade credit borrowing appears on company's balance sheet as an account payable. A new venture should monitor net credit to understand a firm's position as a net source or a net user of funds. Oftentimes, opportunity costs associated with trade credits are expensive. Competition in an industry defines the availability of trade credit and is uniform in a given industry.

Factoring

Factoring is generated when a venture sells the account receivables incurred while offering trade credit. A factor is a specialist who buys an account and manages the collection activities. Factoring can be with recourse or without recourse. Factoring with recourse means that if a customer defaults, the ventures is liable to pay back the factor. The three basic parts of a factoring transaction are the advance, the reserve and the fees for handling collection, and the risk and explicit interest on the funds that is advanced. Factoring is attractive to a cash poor venture until it grows to a size that makes integrating the collections function more economical or for ventures with geographically dispersed buyers and with few repeat customers.

Franchising

The franchisor establishes a business format and offers franchising opportunities to prospective franchisees. In this approach, a franchisor expands the size and the geographic reach of the business rapidly without the burden of raising capital exclusively.

Mezzanine capital

Mezzanine capital is raised after a firm has established a record of positive net income with revenues approaching $10 million or more. Such financing comes in the later-stage growth of a firm and is, generally, a hybrid form with characteristics of senior debt and common equity.

Private placements of equity and debt

This source of financing can be attained by selling equity or debt securities to a small number of investors by means other than a public offering. By doing so, a new venture can avoid the complex , ongoing reporting that would be required if it were to raise capital in a public market. Also, strategic information about the venture stays hidden through private placement. The SEC plays a major role in private placements by regulating the number of offerees, the relationship of the offerees to the issuers, the number of units to be sold, the size of the offering, and the manner of the offering. the SEC makes it mandatory for private placements to have sophisticated investors.

Organizational forms and associated financial aspects

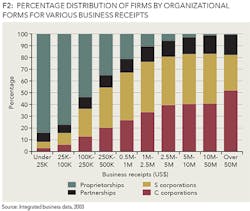

For instance, S-corporation organization suits ventures in an early stage when operating losses are expected, as the 'S' form allows losses to be passed through to owners. When a venture needs to access larger capital sources or if early owners are looking to exit, it is better suited organized as a C-corporation. C-corporations and limited partnerships can help ventures achieve long-run capital needs with passive involvement from investors. However, C-corporations and limited partnerships differ when it comes to transferability of ownership and tax treatment of earnings. (See Table 1.)

For new ventures, limited liability is an essential first step to large-scale fundraising from investors who wish to play passive roles in the venture. Limited liability offered by a "limited liability company" and C-corporation offers protection to entrepreneurs. If raising large amounts of capital is not important, a venture could be organized as a general partnership. Partners are subject to unlimited liability, but venture earnings are able to flow through to the partners untaxed. Figure 2 shows ventures choosing S-corporations in the $100k-250k business receipts range. Also, there is an increase in C-corporation percentage for ventures reporting business receipts of $1 million or more.

Case study: financing a new fluid injection technology

Early adoption of fluid injection technology was made possible by loans based on confidence on volume increase in oil and gas production. Credit analysis for these loans involves conditions more complicated than primary production. The engineering procedure for financing such projects involves the highest possible standards in determining oil and gas reserves, production rates, operating net revenue, and fair market value. Risks to lenders are increased with increased dependence of reserves and production rates on success of fluid injection. A few factors that must be considered when framing such a loan are: legal restrictions and the credit policy of lenders, the timing of the fluid injection project, the performance history of a remedial well, the remaining primary reserves, and the interest percentage that the borrower holds in the project. The determination of a loan amount and a repayment schedule is influenced by lack of experience and uncertainties in the new technology. From a financial perspective, fluid injection technology falls into two categories: seasoned methods (e.g.. water flooding, gas injection) and experimental methods (miscible flood, steam injection). As in any type of financing, risk is minimized by diversifying loan collateral or securities. Diversification is accomplished by including as collateral assets that are not candidates for fluid injection or by including fields with several fault blocks that will minimize cost of operation. Examples of situations on which fluid injection loans were made are presented in Table 2. Financing fluid injection projects is non-recourse in nature. Involved risks must be appraised.

Loan soundness for varying degrees of project success should be framed as follows:

- Forecast of dedicated revenue has to be made for at least 10 years for continued primary, successful secondary and partially successful secondary success.

- Reserves, future gross revenue, dedicated revenue, loan (at desired interest) and debt servicing (principal and interest) should be calculated for the three possible project success scenarios.

- Finally, loan soundness is calculated at current crude prices and future crude prices. Calculation of loan soundness is done based on the period of the loan, the dedicated revenue to loan ratio, the dedicated revenue to debt service ratio and the percentage of dedicated revenue remaining at the three different loan down payment scenarios.

About the author

Siddharth Misra is a final year Doctoral candidate in the Petroleum Engineering Department of the University of Texas at Austin. He has worked on formation evaluation projects in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, USA, Germany, India, and Italy. He can be reached on LinkedIn at sidmisra29.