US shale boom benefits Asian buyers

Asian LNG importers fighting oil-indexation in contracts

Phil Casey, for RBN Energy

Using the US natural gas production boom to promote the idea of a sustainable "global gas glut," Asian importers have successfully managed to chip away at the longstanding oil-indexed pricing mechanism for liquefied natural gas over the past two years. While oil-indexation in LNG contracts will certainly not disappear overnight, the shale revolution has provided gas importers with significant negotiating leverage and a new degree of pricing flexibility. Today we examine the trend toward more US-centric LNG pricing.

In January 2012, Cheniere Energy signed a 20-year agreement with Korea Gas Corporation (KOGAS) to supply 3.5 million tonnes per annum (MMtpa) of LNG from its Sabine Pass facility (equivalent to 0.5 Bcf/d) for a $3/MMBtu liquefaction fee plus 115% of the current Henry Hub natural gas price. [Note: the process of natural gas liquefaction requires lowering the temperature of the gas to -263 Fahrenheit.]

Subsequent contracts based on Henry Hub prices have followed suit. In November 2012, Japanese power utility Kansai Electric signed a 15-year import contract with BP Singapore with Henry Hub natural gas as the price basis. That agreement marked Japan's first-ever long-term LNG import contract fully linked to a gas benchmark. More recently in 2013, Freeport LNG in Texas signed 20-year tolling agreements with Asian industrials Toshiba (Japan) and SK (Korea) for a premium of $7/MMBtu over Henry Hub.

These developments are historic because Asian LNG prices have long been linked to the monthly average of a basket of imported crudes known as the Japanese Crude Cocktail, or JCC. This linkage of LNG to oil prices is also referred to as oil-indexation. The pricing of JCC contracts generally reflect the fact that one thousand cubic feet of natural gas (Mcf) contain one-sixth (16.67%) the energy content of a barrel of oil – a relationship often referred to as "oil parity." In simplified terms, the pricing formula for Asian LNG is therefore: (0.1667 x JCC) + a negotiated premium.

Typically, the contracts are also designed to protect buyers and sellers from exceptionally high or low oil prices. For example, contract price increases are often flattened to lessen the burden on the buyer when oil prices exceed a pre-agreed band ceiling or the supplier when oil prices fall below a band floor. The premium component of the LNG contract can also be adjusted to compensate for extreme volatility in oil prices.

Under a JCC formula a crude basket price of $100/bbl would yield an LNG import price of $16.67/MMBtu + the premium, a rough proxy of what Asian markets were paying in January 2014 – $18.95/MMBtu, according to the Platts Japan/Korea Marker (JKM). With the US natural gas benchmark (the Henry Hub in Louisiana) currently trading at $4.93/MMBtu (Feb. 6, 2014), LNG prices in the Far East are approximately three and a half times higher than what US buyers are paying. And of course US natural gas prices are considerably higher now than they were before this year's harsh winter.

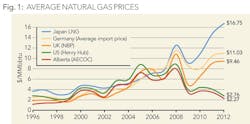

This disparity between US natural gas prices and crude – referred to many times in RBN blogs in our analysis of the breakdown of the traditional crude- to-gas ratio as a result of the shale revolution – has led to a decoupling of regional gas prices since 2006. Asian nations have been particularly hard hit. Figure 1 shows how US and Canadian prices fell well below equivalents in Japan and Europe during 2012.

The resulting higher energy costs have had a profoundly negative economic impact on Asian economies in general and in particular on Japan's balance of payments. Traditionally a net exporter, Japan has recorded 17 straight months of trade deficits, largely due to inflated LNG prices after the Fukushima disaster (Source: Bloomberg, 11/19/2013). Unhappy with these developments and emboldened by the growing prospect of natural gas exports from North America, prominent Asian buyers led by Japan and India have sensed the opportunity and formed a consortium to aggressively lobby for lower LNG prices. Leading importers in Asia are clearly frustrated with the persistence of oil-indexation in LNG contracts and seem motivated to implement new pricing arrangements.

Under normal market conditions, Japan and South Korea would hold significant negotiating leverage as the largest importers in an increasingly gas-saturated world. However, a lack of domestic hydrocarbon resources and a shift away from nuclear energy post-Fukushima have partially offset this advantage. Suppliers are well aware of the increasing reliance of Asian economies on natural gas imports, as illustrated in Figure 2. The chart shows compound annual growth rates (CAGR) of 7.87% in Asian LNG demand through 2014 while European and North American demand is declining and Latin America demand is flat.

So for natural gas producers looking to export LNG the question of how to price their long-term contracts with Asian buyers have become delicate. On the one hand, nations like Japan and South Korea remain heavily dependent on a reliable stream of LNG imports. And China's appetite for natural gas is expected to more than double between 2013 and 2020 (see Figure 3).

In the circumstances, Asian buyers should theoretically be price-takers. On the other hand, as shale discoveries increase and more LNG projects come on-stream across the globe, producers fear being undercut by their competitors. Since most LNG projects require multi-billion dollar investments to build liquefaction facilities, they cannot be financed until the pre-contracting of future output is securely in place. As a result, the producer's haste to secure long-term commitments plays into the hands of buyers looking for lower prices.

The looming possibility of cheap US gas exports flooding the market has clearly unnerved producers and seems to have temporarily tipped negotiating power back to Asian importers. It is not just the dramatic rate of increase in US domestic gas production in the shale era that has overseas competitors racing to sign deals with Asian buyers. US producers also have an important brownfield cost advantage because many LNG export projects are simply retrofits to previously constructed LNG import facilities along the US Gulf and East Coasts that were built to meet growing demand before the shale revolution was recognized by the broader market.

These projects are able to add liquefaction capacity at relatively low cost compared to overseas competitors starting from scratch ("greenfield" projects). Placed head-to-head in the market, greenfield LNG projects will therefore have greater difficulty competing on price against their US counterparts.

Asian buyers are also likely to favor secure supply sources in the United States over projects in more politically volatile regions like East Africa. Argentina's renationalization of YPF in 2012 served as a stark reminder of the great risk in some of these markets.

Furthermore, the one major cost advantage Australian and East African projects hold over American exports – geographic proximity to key Asian markets – will soon be lessened. With a widened Panama Canal planned for 2015, the shipping distance from the US Gulf Coast to Asia for large LNG tankers will drop from 16,000 to 9,000 miles. Subsequently, the freight cost from the US Gulf Coast to Japan should fall from around $2.50/MMBtu to $1.40/MMBtu, though this is variable depending on the new canal toll fees. [We should note here that a recent dispute between the Panama Canal and its contractors could now delay completion of the expansion beyond 2015.]

Nevertheless, a growing sense of urgency is enveloping LNG producers outside the United States. The race is on to sign contracts, construct facilities, and bring projects online before US exports cut into their already-thin margins or render them commercially unviable. And slowly but surely, the US Department of Energy is granting approvals for LNG exports. Such DOE approval is required before US terminals can export LNG – either to countries inside the North America free trade area (FTA – where there is little demand for LNG) or outside (e.g. Asia and Europe at the moment – where most demand resides).

In 2013 the DOE granted non-FTA export approval to three US LNG projects. As of Dec. 6, 2013, the DOE has approved 41 Bcf/d of natural gas exports – about 35 Bcf/d to FTA countries and 6.4 Bcf/d to the more important non-FTA nations. A further 23 applications are currently under review for non-FTA exports totaling 35 Bcf/d.

In conclusion, rising competition between LNG suppliers to secure long-term contracts and the implied threat of cheaper US exports coming down the pike has provided Asian buyers with greater ammunition to negotiate prices based on the Henry Hub US natural gas benchmark. On the whole, these importers should benefit from a variety of factors converging to place net downward pressure on LNG prices including increased US shale production, rising US exports, the expansion of the Panama Canal, and the formation of a consortium of Asian buyers. So while oil-indexation in LNG contracts will certainly not disappear overnight, the shale revolution has provided Asian gas importers with more negotiation leverage and a new degree of pricing flexibility.

About the author

Phil Casey is a graduate of Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business where he double-majored in finance and international business. He went on to receive his master of science in energy and finance from HEC Paris. He attended the Chicago Mercantile Exchange's inaugural School of Managed Futures in Manhattan and passed the FINRA Series 3 (National Commodity Futures) exam in 2012. Casey is currently interning in the M&A team at Santander Global Banking & Markets in Paris, France.