Shipping, market constraints poised to slow US crude export growth

Multiple constraints are lining up against the continued rapid growth of crude oil exports from the US. Moving from the infrastructural through the geopolitical, these include bottlenecks in getting US-produced crude to the Gulf Coast for shipment, limitations on export capacities of US Gulf Coast ports, the continued inability of very large crude carriers (VLCC) to transit the Panama Canal, and the looming specters of increases in both Chinese tariffs and Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) production.

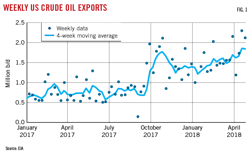

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) crude oil exports averaged 1.6 million b/d through mid-May 2018, up from 1.1 million b/d the year before and 500,000 b/d in 2016. This rapid growth has occurred despite the inability of VLCCs to fully load directly at US ports, relying instead on partial loading and using lightering vessels to shuttle crude to them.

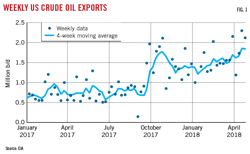

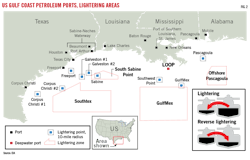

Reverse lightering (moving liquids from a smaller vessel to a larger one) is so pervasive that even before the surge in crude exports the two highest volume crude and petroleum products US Gulf Coast export ports were both lightering zones in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. According to 2015 data from the US Maritime Administration (MARAD), South Sabine Point lightering zone and Southtex lightering zone each moved 249 million dwt. The Port of Houston was the largest volume onshore port that year at 193 million dwt (Figs. 2-3).

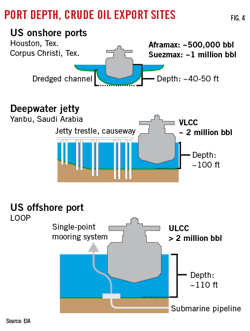

US Gulf Coast onshore ports such as Houston and Corpus Christi can fully load Aframax (500,000 bbl) and Suezmax (1 million bbl) tankers. The deepwater jetty at Yanbu, Saudi Arabia, by contrast, can fully load a 2-million bbl VLCC (Fig. 4).

Enter LOOP

The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), a joint venture of Marathon Pipe Line LLC, Shell Oil Co., and Valero Terminalling and Distribution Co., was organized as a crude import site in 1972 and offloads vessels up to and including ultra large crude carriers (ULCC, > 2 million bbl). It exported its first cargo in February 2018, the first fully loaded VLCC to leave a US Lower 48 port.

LOOP consists of three single-point mooring (SPM) buoys and a marine terminal consisting of a two-level pumping platform and a three-level control platform, 18 miles off the Louisiana coast. Water depth at each SPM is 115 ft. The Clovelly Hub, 25 miles inland, is connected to the port complex by a 48-in. OD pipeline. Clovelly provides interim storage for crude before it is delivered either to tankers for export or to refineries on the Gulf Coast and in the Midwest.

Oil is stored in eight underground caverns capable of holding a combined 60 million bbl. There are three dedicated caverns for streams coming in from the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, two for Shell’s Mars field, and one for BP’s Thunder Horse. Clovelly also has an above-ground tank farm consisting of fifteen 600,000-bbl tanks and seven 375,000-bbl tanks, for a combined total of nearly 72 million bbl of crude storage.

LOOP’s transition to exports required modifications to pump stations, valves, and piping from Clovelly to the mooring point, including a booster station in Port Fourchon, La., to make the system bidirectional.

Consultancy Genscape Inc. reported that the Shell-chartered VLCC Shaden was loaded in February with Mars medium sour crude for delivery to China’s state-owned Sinopec. Genscape went on to say that “medium sour crude shipments from LOOP could begin to challenge Middle Eastern grades that have traditionally fed Chinese refiners,” supported by the Shanghai International Energy Exchange’s new crude contract.1

The ability to fully load VLCCs will likely also draw interest from crude producers outside LOOP’s immediate vicinity eager to reach export markets as efficiently as possible. Pipelines feeding into Clovelly from onshore basins are limited, however, the site having been developed primarily to move crude imports and offshore production to refiners in both Louisiana and the midcontinent. Shell’s 375,000-b/d Zydeco pipeline, running 350 miles from Houston to Louisiana destinations including Houma, St. James, and Clovelly, is the only system currently able to move crude produced in the Permian and other outside-the-region basins to LOOP.

Genscape posits that the desire to export barrels from LOOP could advance both reversal of the Marathon Pipe Line LLC-operated 1.2-million b/d Capline pipeline currently running from St. James to Patoka, Ill., and subsequent connectivity from St. James to LOOP. With a Patoka starting point, a reversed Capline could more directly move both heavy western Canadian and lighter Bakken crudes to LOOP.

But even if flows on the 40-in. OD Capline are reversed, southbound service wouldn’t begin until second-half 2022 at the earliest and initial capacity would be 300,000 b/d.

Crude currently travels south from Patoka on the Energy Transfer Crude Oil Pipeline, with delivery to Nederland, Tex., outside Houston.

Corpus Christi expansion

The Port of Corpus Christi is also expanding. Its commissioners in April 2018 approved $217 million in bonds to expand the Corpus Christi Ship Channel and improve other infrastructure. The channel expansion will cost $327 million, $102 million of which will come from the port’s bond issue with the federal government the current likely supplier of the balance.

The ship channel expansion will deepen the 36-mile waterway to 54 ft and widen it to 530 ft, big enough to accommodate a fully loaded Suezmax tanker. Both channel expansion and a separate project to build a taller Harbor Bridge—increasing clearance to 205 ft from 138 ft—are scheduled for 2021 completion.

Less clear is when fully loaded VLCCs will be able to navigate the port and ship channel. But companies operating terminals at the port are already planning for that future. In May 2017 Occidental Petroleum chartered VLCC Anne to dock at its Ingleside Energy Center crude terminal to evaluate any modifications that might be required to regularly load such vessels.

Anne entered the port, docked, was partially loaded, and exited the port successfully. Oxy in September 2017 said it intended by late 2018 to complete installation of multiple loading arms at its terminal to allow for regular VLCC loading.

Buckeye Partners LP in April 2018 formed a joint venture with Phillips 66 Partners LP and Andeavor to develop a new deepwater, open access marine terminal in Ingleside, Tex. The South Texas Gateway Terminal will be built on a 212-acre waterfront parcel at the mouth of Corpus Christi Bay. It will serve as the primary outlet for crude oil and condensate volumes delivered by the planned Gray Oak and South Texas Gateway pipelines from the Permian basin.

The terminal, to be built and operated by Buckeye, will offer 3.4 million bbl of crude storage and two deepwater docks capable of berthing VLCCs. The terminal can be expanded to include over 10 million bbl of storage as well as multiple additional docks and other inbound pipeline connections. The owners expect the terminal to enter service by end 2019. Buckeye will own a 50% interest in the joint venture and Phillips 66 and Andeavor will each own 25%.

Between Corpus Christi and Louisiana, further up the Texas coast, Enterprise Products Partners LP has brought VLCCs into its Texas City marine terminal. The terminal’s 45-ft draft, however, limited loading to slightly more than half the vessels’ roughly 2-million bbl capacity.

Enterprise plans to develop a deepwater crude oil export terminal 80 miles off the Texas Gulf Coast. The terminal would be capable of fully loading VLCCs. The company has started front-end engineering and design and preparing applications for regulatory permitting.

Permian to Corpus

Epic Midstream Holdings LP is building a 730-mile crude pipeline between the Permian basin and Corpus Christi, capable of carrying 590,000 b/d starting in 2019. The line will run alongside Epic’s NGL pipeline for large portions of its length.

Buckeye expects its 700,000-b/d Gray Oak line to enter service fourth-quarter 2019, delivering Permian production to Corpus Christi, Sweeny, and Freeport, Tex. The company’s South Texas Gateway Pipeline will deliver both to Buckeye’s new terminal and to the Houston area by 2020, using 30-in. OD pipe to move more than 600,000 b/d.

Plains All American Pipeline LP, meanwhile, plans to build its 585,000-b/d Cactus II pipeline from the Permian to Corpus Christi-Ingleside, using a combination of newbuild and existing pipe and targeting a third-quarter 2019 startup.

Finally, Magellan Midstream Partners is examining a variety of options for either expanding its current system out of West Texas, adding newbuild infrastructure, or a combination of the two. The company hopes to narrow its options in time to have extra capacity in operation by 2020.

Magellan held an open season first-quarter 2018 to deliver crude from the Permian and Eagle Ford basins to both Corpus Christi and Houston. The system described in the open season would include 375 miles of newbuild 24-in. OD line from Crane, Tex., to Three River, Tex. From Three Rivers shipments could continue to either Houston (200 miles) or Corpus Christi (70 miles) on additional newbuild line.

Larger Permian crude oil producers have the flexibility and resources to continue producing even as price discounts in Midland widen versus West Texas Intermediate’s Cushing, Okla., benchmark. Smaller operators, however, are closely monitoring both price differentials and the timing of new pipeline capacity as they try to determine the degree to which they might have to slow or shut in production.

And then Panama

The expansion of the Panama Canal in June 2016 substantially increased traffic by both LNG and LPG carriers leaving the Gulf Coast bound for Asia. Transits by LPG vessels rose to 876 in 2017 from 449 in 2016, according to the Panama Canal Authority. LNG transits accelerated to 163 from 17 the year before.

VLCCs, however, still can’t pass through Panama’s locks, the largest size vessel up to the task being Neopanamax. Old Panamax vessels could measure up to 965 ft long, with a 106-ft beam and 39.5 ft draft. Neopanamax ships can measure 1,200 ft by 160 ft by 50 ft, boosting capacity to 400,000-600,000 bbl from 300,000-500,000 bbl, still a far cry from the VLCC’s 2-million bbl.

Higher shipping costs to move US crude to Asian markets will have to be made up for in lower-priced material if US exports are to continue their expansion.

Demand and supply

Chinese independent refiners have slowed down their purchases of US crude in recent months and may remain entirely out of the market for several months to come, according S&P Global Platts, citing growing uncertainties on the part of non-state customers regarding the effects of the tariff war between the two countries. Independent refiners were responsible for nearly one quarter of all US crude imported into China during 2017.

Much of current US production is either too light or too sour to be efficiently processed in China even on predictable terms. The average barrel of crude processed so far in 2018 by Chinese independent refineries had a 28.3° API gravity and 0.93% sulfur content, according to Platts.2 In 2016 the vast majority of Lower 48-sourced production was already 35.1° API gravity or higher (with the largest single range 40.1-45.0),3 and this has only increased in light of surging Permian-basin production.

India is one potential alternative to China as a destination for US crudes, and shipments there are already increasing, but its refiners too prefer a heavier barrel to that typically exported by US producers.

Further complicating the role of US exports in the global crude market is OPEC’s June 22, 2018, decision to roll back overcompliance with its November 2016 production-cut targets. Cuts intended to remove 1.8 million b/d from the global market took out 2.2-million b/d (OGJ Online, June 25, 2018). OPEC ministers said the effective increase after the June meeting would be less than 1-million b/d, likely placing it somewhere between that level and the 400,000 b/d difference between target and reduction.

References

1. Arno, D. and White, D., “First Crude Export Set to Depart from LOOP, Epitomizing US Gulf Coast Supply Chain Development,” Genscape, Feb. 16, 2018.

2. Newberry, C., Xu, D., and Zhou, O., “Analysis: China’s Independent Refineries Shy Away from US Crudes,” S&P Global Platts, June 21, 2018.

3. Geary, E., “The API Gravity of Crude Oil Produced in the US Varies Widely Across States,” US EIA, Today In Energy, Apr. 19, 2017.

About the Author

Christopher E. Smith

Editor in Chief

Chris joined Oil & Gas Journal in 2005 as Pipeline Editor, having already worked for more than a decade in a variety of oil and gas industry analysis and reporting roles. He became editor-in-chief in 2019 and head of content in 2025.