US pipeline operators face cybersecurity compliance deadline

A directive issued May 28, 2021, by the US Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Transportation Safety Administration (TSA) ordered pipeline operators to check and report on the cybersecurity of their pipeline systems within a month. Security Directive Pipeline-2021-01 was published after a ransomware attack led to the 6-day shutdown of Colonial Pipeline Co.’s 5,500-mile pipeline, which carries 45% of the US East Coast’s gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel.

Colonial paid a ransom to the DarkSide cybercriminal gang so the operator could regain access to its information technology (IT) systems, that had been locked by the ransomware. The operator said it would otherwise have cost tens of millions of dollars to check and fully restore its systems over months.1 It also stressed that the attack had affected only its IT and had not resulted in DarkSide gaining access to operational technology (OT). OT covers software and hardware—e.g., supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and programmable logic controllers (PLCs)—that monitor and control assets, specific equipment such as valves, events, and processes.

Research by advisory firm Gartner suggests that 60% of companies operating critical infrastructure are only in the earliest stages of maturity when it comes to having integrated and optimized cyber security in place for OT and cyber-physical systems. These companies are aware of the risk but are unlikely to have implemented robust solutions.2

"If pipeline companies show the same spread of maturity about OT cybersecurity as Gartner found among companies in general, it will likely take a great deal of effort for them to rigorously apply existing US cyber-guidelines for pipeline systems,” said Jim Ness, regional business manager, cybersecurity, North America at DNV.

Despite being confined to IT, the Colonial Pipeline incident has upped the stakes in the daily battle that energy infrastructure operators worldwide are waging against malicious cyberattacks. Even though the attackers did not access Colonial’s OT, the perceived risk that it might have been able to was sufficient for the company to follow its own protocol by ordering the immediate precautionary shutdown of its pipeline.

Pipeline operators worldwide see with increasing clarity that greater connectivity between IT and OT for operational efficiency brings more complex and greater cybersecurity challenges. Therefore, the pipeline industry needs to be sure that its approaches, tools, and resources for cyber security at least comply with regulations.

“Naturally, regulators react to incidents by tightening up on compliance checks. A good example is the publication of the new directive in response to the Colonial Pipeline attack. Some operators will find it necessary to go beyond basic compliance with regulations to implement best practice for some degree of future-proofing their cyber security,” said Ness.

Complying with US pipeline cybersecurity regulations

Under the directive TSA-specified pipeline owner-operators must:

• Review their current activities against TSA recommendations for pipeline cyber security to assess cyber risks, identify any gaps, and develop remediation measures.

• Report the results of these actions to the TSA and the DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

• Report cybersecurity incidents to CISA.

• Designate a cybersecurity coordinator who is required to be continuously available to TSA and CISA to coordinate cybersecurity practices and address any incidents that arise.

Several risk-assessment frameworks and models can help to perform the cybersecurity gap analysis required under the TSA’s directive.

Assessing pipeline cybersecurity risk

DNV Recommended Practice (RP) DNVGL-RP-G108 Cyber security in the oil and gas industry based on IEC 62443 focuses on how to achieve cybersecurity in critical oil and gas infrastructure. It is intended for all aspects of an enterprise involved in ensuring that cybersecurity is taken care of in industrial automation and control systems (IACSs), including asset owners, system integrators, product suppliers, service providers, and compliance authorities. The RP clarifies the responsibilities shared between these parties, and describes who performs the activities, who should be involved, and the expected inputs and outputs.

DNVGL-RP-G108 is based on applying IEC 62443, a series of standards adopted by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) as a framework to address and mitigate current and future security vulnerabilities in IACSs. The DNV RP also incorporates aspects of NIST SP 800 standards from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology. IEC 62433 itself evolved from the ISA99 standards developed by the US-based International Society of Automation (ISA).

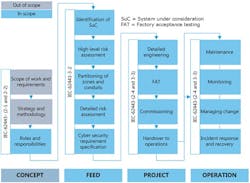

The DNV RP and IEC 62443 standard cover the full lifecycle of a cyber asset (see figure).

The risk assessment elements of DNVGL-RP-G108 make use of well-known methodologies applied in process safety analysis. While it is intended for capital projects, the principles can also be applied for assets in operation.

Consequently, DNVGL-RP-G108 can be applied for cyber security gap assessment of existing pipeline systems, as the TSA directive requires. This has already been applied on several greenfield and brownfield installations, on- and offshore, as well as in the maritime and power and utilities sectors.

Proposing alternative measures to the US pipeline regulator

In publishing the new directive, TSA also told pipeline owner-operators unable to implement the measures prescribed that they may seek approval both for proposed alternative measures and for the basis for submitting such measures.

“Meeting the June 25, 2021, deadline established by the directive may be a struggle for many pipeline operators regarding its cyber risk and gaps assessment requirements if they do not already have many of the underlying data sets in place,” according to Ness. These data could include, among others, asset inventories, up-to-date network drawings, supporting policies and procedures, training programs, drill schedules, risk assessments, response plans, and identification of the responsibilities of key cyber security roles.

“In cases where gaps are too significant to address by the deadline, all operators should focus on developing practical, risk-based gap closure plans, prioritizing areas of greatest risk reduction,” Ness added.

Resourcing better pipeline cyber security

Appendix A of the TSA guidelines lists information that must be refreshed and reassessed periodically. Its requirements highlight information that corporate officers of pipeline companies will regularly require from chief information security officers (CISOs) or their equivalent.

Ness said that to be confident that activities to collect this information are being performed, CISOs will need to verify that company policies and procedures reflect the requirements. “They will also have to ensure that verification-audit activities are happening at appropriate intervals, and that these confirm the effectiveness of the company’s cyber security programs.”

References

1. Kelly, M.R., Fuller, J., and Kenin, J. “The Colonial Pipeline CEO Explains The Decision To Pay Hackers A $4.4 Million Ransom,” National Public Radio, June 3, 2021.

2. Thielemann, K., Voster, W., Pace, B., and Contu, R., Gartner, “Market Guide for Operational Technology Security,” Jan. 13, 2021.