Direct lithium extraction from brine emerging as go-to mining technique

Key Highlights

- Emerging DLE technologies offer higher recovery efficiency, faster production times, and a smaller environmental footprint compared with traditional methods like solar evaporation.

- Current pilot projects and assessments suggest US reserves could supply domestic lithium needs for decades, with potential reserves increasing at higher lithium prices.

Khosrow Biglarbigi

Marshall Carolus

Vanessa Murakami

INTEK Inc.

US demand for lithium, in the forms of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide, is expected to grow in response to wide-spread vehicle electrification and the adoption of solar storage. A February 2024 study from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) forecast that by 2032, US demand for lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) would reach 340,000 tonnes/year (tpy) for battery electric vehicles (BEV). An additional 200,000 tpy of LCE would be required to meet US demand in other sectors.1 In 2023, the US demand was 70,000 tonnes of LCE, while domestic supply was 4,000 tonnes in 2022.2 3 This disparity in domestic demand and supply causes the US to be heavily reliant on foreign imports from China and other countries.

Historically, lithium has been produced using two approaches: hard rock mining of spodumene deposits, as seen at the Greenbushes mine in Australia or solar evaporation and concentration of lithium-rich brines, as seen in the lithium triangle in Argentina, as well as solution mining. But domestic sources for conventional methods, such as hard rock mining and solution mining are limited, and the solar evaporation method is limited in terms of efficiency, time to production, and environmental concerns.

New direct lithium extraction (DLE) technologies are being developed to extract lithium from oil and gas produced waters as well as brines from saline aquifers or geothermal deposits. Some of these technologies have reached the pilot and early commercial phases in the US, with promising results. DLE extracts the lithium from the brine for refining into purified LCE or lithium hydroxide (LiOH) which are both suitable for batteries and other purposes.

This article provides an overview of current and projected lithium demand in the US and examines the potential application of emerging DLE technologies, including ion exchange, membrane separation, and adsorption. These technologies are being developed to extract lithium from brine aquifer, oil and gas produced water, and geothermal resources. An assessment using a new analytical system determined production potential for these technologies in the US.

The approach, methodology, and results of the assessment are provided, including potential production, reserves, and socio-economic benefits. These benefits include Federal and state revenues, other public-sector revenues, contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP), new jobs, and the value of imports avoided because of increased domestic lithium production.

DLE technology, refining

DLE is the process by which lithium concentrate (eluate) is extracted from a lithium-rich brine. DLE includes adsorption, ion exchange, membrane (nano-filtration), electro-chemical, and other approaches. The eluate is refined into battery-grade LCE or LiOH.

DLE, has many advantages compared with other lithium extraction methods, specifically solar evaporation. DLE has higher recovery efficiency, faster production time, and a smaller environmental footprint.

In the context of this article, DLE refers to the entire extraction and refining process and has six major steps:

- Production of a lithium enriched brine. The brine could be associated with water from oil and gas activities, produced from an aquifer which underlies the reservoir, produced as part of a geothermal system, or from other sources.

- Pretreatment of the brine is pre-treated to remove hydrocarbons, solids, hydrogen sulfide, magnesium, and other salts which would reduce the efficiency of the extraction technologies.

- Application of DLE to selectively extract the lithium from the brine, usually in the form of lithium chloride suspended in an eluate.

- Lithium chloride purification and concentration to remove water and other impurities from the eluate so that only the lithium chloride remains.

- Conversion of the lithium chloride to LCE or LioH through crystallization, washing, grinding, and other steps.

- Reinjection of spent brine into the producing formation or another formation through disposal wells.

DLE has a technology readiness level (TRL) of 4 to 9, depending on the method being used.4 Globally, there are 13 operating DLE projects, three of which are in China, that are projected to collectively produce 120,000 tpy of lithium.5 At present, there are no commercial-scale DLE projects in the US. But a number of pilot projects are underway and new commercial projects are being planned.

The Critical Material Innovation (CMI) hub of the US Department of Energy (DOE), has classified DLE technologies into five categories; adsorption, ion exchange, solvent extraction, (electro) membrane, and electro-chemical:6

- Adsorption based DLE technologies extract lithium chloride from the brine using an aluminum-based or other sorbent. Lithium chloride is then released from the sorbent using a warm lithium chloride solution.4

- Ion exchange typically uses manganese and titanium-based sorbents with specifically adjusted porosity which act as sieves for the lithium and hydrogen ions. The lithium ions are then released using a low-pH solution.4

- Solvent extraction uses the different solubilities of the compounds in the solutions, as well as lithium selective extractants, to form lithium complexes which are then stripped from the solution. Usually, hydrochloric or sulfuric acids are used to recover the lithium complexes. This approach, which can also be used as a post-extraction treatment for other DLE technologies, has environmental risks.4

- Membrane extraction can be conducted using pressure-assisted processes such as microfiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis, or via potential-assisted (electro) processes such as electrodialysis. Nanofiltration, and other pressure-assisted processes, were originally designed for water treatment and desalinization but can be applied to lithium extraction. However, high concentrations of non-lithium salts in the brine can cause scaling and impact the efficiency of this lithium extraction process. Electrodialysis and other potential-assisted processes are being used in other DLE approaches to convert lithium chloride to LCE or LiOH. Electro-membrane technologies use lithium-selective membranes in potential-assisted processes.4

- Electro-chemical DLE technologies are still in early-stage development and capture lithium “on or inside electrodes in an AC or DC power mode system.”4 This technology has previously been applied to the extraction of nickel, cesium, and copper.

As of May 2024, CMI had identified three companies which had reached the commercial stage of their DLE technologies in the adsorption and ion exchange categories.6

Methodolgy

CritSAT is an analysis tool developed to evaluate the potential production of critical minerals and rare earth elements in the US. It evaluates lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and several rare-earth elements. Lithium production is modeled for hard rock and solution mining of spodumene and other mineral resources and also for DLE technologies. The model is designed to estimate the technical and economic production and reserves for these minerals under a wide range of technological, economic, developmental, and fiscal-regime scenarios to support strategic planning, resource-technology mapping, and cost-benefit analysis.

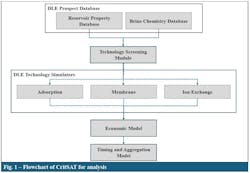

Fig. 1 shows the conceptual flowchart for the submodule of the CritSAT in charge of evalua DLE. The submodule includes a DLE prospect database, a screening module, technical simulators, an economic module, and a project selection and timing module.

DLE-prospect database

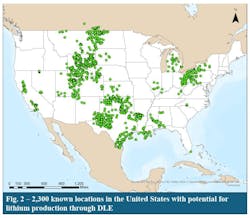

The prospect database contains information for more than 2,300 locations in the US with the potential for lithium production through DLE (Fig. 2). It includes oil and gas produced waters, brine aquifers, and geothermal resources. The prospect database was constructed using an in-house oil and gas resource database containing the locations, petrophysical properties, and historical production data for more than 25,000 oil and gas fields and reservoirs in the US. Combining it with a publicly available US brine chemistry database, resulted in a prospect database that includes the location, depth, pay, permeability, and porosity of candidate reservoirs as well as their concentrations of lithium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and other salts and minerals.

The analytical system currently contains three DLE technology simulators: membrane separation, ion exchange, and adsorption. These simulators’ calculations were developed according to petroleum engineering principles, process data collected from feasibility studies, and 3D simulations of the movement of reinjected spent brine through a formation. For each potential project, the simulators calculated a 25-year profile for:

- Brine production.

- Spent brine reinjection.

- Breakthrough time for the spent brine and resulting dilution of the original lithium concentration.

- Average lithium concentration for the produced brine.

- Volume of brine extracted.

- Volume of LCE or LiOH refined.

Economic model

Project economic feasibility is evaluated using a cashflow model. The model details capital and operating costs for different phases of the project. These costs include: drilling the producing and injecting wells, brine production and transportation, facility construction, separation of the lithium from the brine, production of LCE or LiOH, storage and shipment of finished products, brine disposal, and energy requirements. Current Federal, state, and local tax structures are used to calculate the royalty and other Federal and state outlays.

Evaluating economically viable projects to determine if their drilling and capital investment requirements can be met, with those receiving a positive determination scheduled for development based on historical market penetration of similar technology. Project-level results are aggregated to local, regional, and national levels, as presented in this article.

Assumptions

The results presented in this article are subject to the following assumptions:

- Adsorption technology is considered to extract the lithium concentrate (eluate).

- The concentrate is refined into LCE.

- Three fixed prices are used for economic analysis ($12,000, $20,000, and $32,000/tonne of LCE, stated in constant 2022 dollars).

- Spent brine (after extraction of the lithium) is reinjected into the same formation and all related costs are considered in the economic analysis.

- 25-year project life.

These prices were selected to bracket likely future LCE prices. Economic analysis conducted for individual projects is aggregated to the national level.

Potential reserves, production

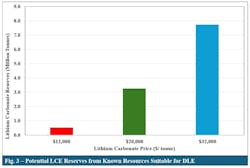

Fig. 3 illustrates the relationship between LCE prices and the amount of economically feasible reserves for DLE. This article defines “reserves” as the cumulative production of economically viable projects for their 25-year life span. At the lower end of the price range of $12,000/ tonne, roughly 0.5 million tonnes of LCE are economically feasible. At the mid-level price of $20,000/ tonne, 3.3 million tonnes of LCE have the potential to be economically feasible. At higher prices, potential reserves increase to about 7.7 million tonnes, equivalent to ~23 years of demand for lithium for use in the electric vehicles at projected US demand levels. The results also indicate that, even at the lower LCE prices, lithium reserves are sufficient to supply a portion of domestic demand which is expected to grow to 540 thousand tonnes/year by 2032.

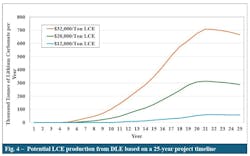

Fig. 4 shows annual LCE production across the analyzed prices. At the lowest price of $12,000/tonne, production takes 11 years to start, reaches nearly 60,000 tpy and remains at that level for the remainder of the forecast period. At $20,000/tonne, production begins in Year 6 and reaches a maximum of 300,000 tonnes. At the highest price of $32,000/tonne, LCE production starts in Year 5 and peaks at 709,000 tonnes. This would be sufficient to meet domestic LCE demand and support an export industry.

These results show that higher LCE prices lead to earlier production start times because of increased economic activity for new DLE projects. The decrease in production after Year 21 is caused by the reinjection of spent brine into the formation and the resulting dilution of the lithium concentration.

Socioeconomic benefits

Widespread development of DLE could benefit local, state, and national economies. The benefits are measured in terms of state and local revenues, federal revenues, contributions to the gross domestic product (GDP), and jobs. State and local revenues are derived from production taxes, state corporate income taxes, commerce taxes, and net proceeds taxes, which vary based on the state in which the project is located. Federal revenues are from federal corporate income taxes as well as federal royalty payments.

State and local governments could gain $37 million at a $12,000/tonne LCE price, and up to $2.6 billion in revenues at the higher price of $32,000/tonne. At the federal level, revenues could reach $500 million at $12,000/tonne, and as much as $27.7 billion in revenue at the higher price of $32,000/tonne.

In addition to government revenues, these projects have the potential to contribute significantly to US GDP. This contribution is estimated at $6.3 billion at LCE prices of $12,000/tonne, and up to $247.3 billion at $32,000/tonne.

Fig. 5 presents an estimate of the new jobs created from DLE projects across the analyzed prices for both direct and indirect employment. Direct jobs range from 2,000 full-time employment (FTE) positions to 56,000 FTE at LCE prices of $12,000/tonne and $32,000/tonne, respectively. Furthermore, up to 220,000 FTE indirect jobs are estimated to be created by these projects at the higher prices.

Analysis limitations

The analysis presented in this article is subject to the following limitations:

- It assumes the use of adsorption technology. The results for ion exchange and membrane technologies are not shown.

- Analysis is based on known resources where sufficient data is available and does not include the entire US resource base. The extent of the entire US resource is not known due to a lack of data.

- DLE is an emerging extraction method, with associated uncertainties that could affect successful development and adoption, impacting the results of the analysis.

- The costs used are based on early-stage data from available prefeasibility reports and may change as projects continue to develop.

- The results presented are potential targets for the analyzed resources, and are not intended to provide likely forecasts for future development of lithium projects in the US.

Realizing lithium’s potential in the US will require a concerted effort between industry and local, state, and federal governments to address problems associated with resource access, permitting, research and development, project economics, and fiscal regimes.

References

- Shang, C.; Slowik, P.; Beach, A., “Investigating the US Battery Supply Chain and Its Impact On Electric Vehicle Costs Through 2032,” International Council on Clean Transportation, https://theicct.org/publication/investigating-us-battery-supply-chain-impact-on-ev-costs-through-2032-feb24/, Feb. 21, 2024.

- Roberts, J., “Why North America needs regional price references for lithium,” Fastmarkets, https://www.fastmarkets.com/insights/why-north-america-needs-regional-price-references-for-lithium/, Apr. 15, 2024.

- Brunelli, K., Lee, L., and Moerenhout, T., “Lithium Supply in the Energy Transition,” Factsheet from the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia | SIPA, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Lithium-CGEP_FactSheet_121223-2.pdf, Dec. 12, 2023.

- Razmjou, A., “Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE): An Introduction – A report exploring the various technologies used for direct lithium extraction (DLE),” prepared for the International Lithium Association, https://lithium.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Direct-Lithium-Extraction-DLE-An-introduction-ILiA-June-2024-v.1-English-web.pdf, June 2024.

- Jennifer, L., “Is Direct Lithium Extraction the Key to Solving the Lithium Shortage Crisis?,” Carbon Credits. https://carboncredits.com/is-direct-lithium-extraction-the-key-to-solving-the-lithium-shortage-crisis/?utm_source=chatgpt.com, August 2024.

- Lograsso, T., “Overview of DLE and Other Technologies,” Critical Minerals Innovation Hub (CMI), presented at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine’s “Brines as a Resource for Critical Minerals” Joint BESR/CER Spring Meeting, May 7, 2024.

Authors

Khosrow Biglarbigi is President of INTEK Inc., and has more 35 years’ experience in evaluating conventional and unconventional oil and gas resources, critical minerals, and strategic materials. Biglarbigi leads INTEK’s critical minerals efforts with both public and private sector clients. He provides strategic and planning support to corporate officers at several private companies developing lithium and rare earth resources in West Texas, the Permian basin, and California. Biglarbigi earned MS and BS degrees in petroleum engineering from the University of Tulsa. He currently serves on the U.S. Advisory Council for the Society of Petroleum Engineering International.

Marshall Carolus is vice-president of INTEK Inc., and has 20 years of experience in oil, gas, and mineral resource modeling, petroleum logistics, supply chain analysis, and technology assessment. He leads INTEK’s modeling efforts related to critical minerals with both public and private sector clients. Carolus developed INTEK’s critical mineral supply analysis tool (CritSAT) which models the resources, extraction and refining technologies, and economics of battery-related critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and manganese. He earned a BS in mathematics from Villanova University in Pennsylvania.

Vanessa Murakami is an environmental analyst with INTEK Inc. and has led and participated in a diverse array of interdisciplinary projects spanning the environmental science and business realms. Shea has contributed to the development of INTEK’s critical mineral analysis system through the identification and analysis of hard-rock and solution-mining resources and projects for lithium and rare earth elements. Murakami has a master’s degree in environment and sustainability management from Georgetown University, Washington D.C.