M&A in the global petroleum industry

A PRIMER FOR ENERGY EXECUTIVES ON OIL AND GAS MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

EUGENE M. KHARTUKOV, MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY, MOSCOW

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the second in a series of two articles by Professor Khartukov about the increasing importance and relevance of mergers and acquisitions in the global petroleum industry. Part 1 ran in the January 2016 issue of OGFJ.

THE TERMS "merger" and "acquisition" are often uttered in the same breath and are often used as though they are synonymous. However, their meanings are slightly different. Whether a purchase is considered a merger or an acquisition really depends on whether the purchase is friendly or hostile and how it is announced. In other words, the real difference lies in how the purchase is communicated to and received by the target company's board of directors, employees, and shareholders.

Like mergers, acquisitions are actions through which companies seek economies of scale, efficiencies, and enhanced market visibility. Unlike all mergers, all acquisitions involve one firm purchasing another. There is no exchange of stock or consolidation as a new company. Acquisitions are often congenial, and all parties feel satisfied with the deal. Other times, acquisitions are more hostile.

In an acquisition, a company can buy another company with cash, stock, or a combination of the two. Another possibility, which is common in smaller deals, is for one company to acquire all the assets of another company. Company X buys all of Company Y's assets for cash, which means that Company Y will have only cash (and debt, if they had debt before). Of course, Company Y becomes merely a shell and will eventually liquidate or enter another area of business.

Another type of acquisition is a reverse merger, a deal that enables a private company to get publicly-listed in a relatively short time period. A reverse merger occurs when a private company that has strong prospects and is eager to raise financing buys a publicly-listed shell company, usually one with no business and limited assets. The private company reverse merges into the public company, and together they become an entirely new public corporation with tradable shares.

Regardless of their category or structure, all mergers and acquisitions have one common goal: they are all meant to create synergy that makes the value of the combined companies greater than the sum of the two parts. The success of a merger or acquisition depends on whether the synergy is achieved.

Synergy is the magic force that allows for enhanced cost efficiencies of the new business. Synergy takes the form of revenue enhancement and cost savings. By merging, the companies hope to benefit from the following:

Staff reductions - As every employee knows, mergers tend to mean job losses. Consider all the money saved from reducing the number of staff members from accounting, marketing and other departments. Job cuts will also include the former CEO, who typically leaves with a compensation package.

Economies of scale -- Yes, size matters. Whether it's purchasing stationery or a new corporate IT system, a bigger company placing the orders can save more on costs. Mergers also translate into improved purchasing power to buy equipment or office supplies. When placing larger orders, companies have a greater ability to negotiate prices with their suppliers.

Acquiring new technology - To stay competitive, companies need to stay on top of technological developments and their business applications. By buying a smaller company with unique technologies, a large company can maintain or develop a competitive edge.

Improved market reach and industry visibility - Companies buy companies to reach new markets and grow revenues and earnings. A merge may expand two companies' marketing and distribution, giving them new sales opportunities. A merger can also improve a company's standing in the investment community: bigger firms often have an easier time raising capital than smaller ones.

That said, achieving synergy is easier said than done - it is not automatically realized once two companies merge. Sure, there ought to be economies of scale when two businesses are combined, but sometimes a merger does just the opposite. In many cases, one and one add up to less than two.

Sadly, synergy opportunities may exist only in the minds of the corporate leaders and the deal makers. Where there is no value to be created, the CEO and investment bankers - who have much to gain from a successful M&A deal - will try to create an image of enhanced value. The market, however, eventually sees through this and penalizes the company by assigning it a discounted share price.

VARITIES OF MERGERS

From the perspective of business structures, there is a whole host of different mergers. Here are a few types, distinguished by the relationship between the two companies that are merging:

Horizontal merger- Two companies that are in direct competition and share the same product lines and markets.

Vertical merger - A customer and company or a supplier and company. Think of a cone supplier merging with an ice cream maker.

Market-extension merger - Two companies that sell the same products in different markets.

Product-extension merger - Two companies selling different but related products in the same market.

Conglomeration - Two companies that have no common business areas. There are two types of mergers that are distinguished by how the merger is financed. Each has certain implications for the companies involved and for investors:

Purchase mergers - As the name suggests, this kind of merger occurs when one company purchases another. The purchase is made with cash or through the issue of some kind of debt instrument; the sale is taxable. Acquiring companies often prefer this type of merger because it can provide them with a tax benefit. Acquired assets can be written-up to the actual purchase price, and the difference between the book value and the purchase price of the assets can depreciate annually, reducing taxes payable by the acquiring company.

Consolidation mergers - With this merger, a brand new company is formed and both companies are bought and combined under the new entity. The tax terms are the same as those of a purchase merger.

Nationalization is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or State. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being transferred to the public sector to be operated by or owned by the state. The opposite of nationalization is usually privatization or de-nationalization, but may also be municipalization.

The first acquisitions occurred in the US petroleum industry in 1977. From then to 2015, nearly 1,070 petroleum-related M&A deals with value not less $100 million each were struck in the world (See Figure 1 and Table 1).

Global petroleum M&A markets saw an impressive 40-fold rise in deal value to $9.24 trillion in 2014 (Table 1), mostly thanks to skyrocketing acquisition activity in the US, where O&G M&A deal values reached 10-yr high of $321.5 billion in 2014 compared to $117.2 billion in 2013.

In the US, according to PwC US, the record-breaking year was primarily driven by a significant level of mega deals (those valued at over $1 billion) - a trend that began early that year and continued throughout the fourth quarter of 2014.

Overall, there were 49 mega deals - for example, the announced $34.6 billion takeover of Baker Hughes by Halliburton and Kinder Morgan's $76 billion acquisition of El Paso Pipeline Partners. Total deal value rose from $71 billion in 2013 to $266.1 billion in 2014.

For the first eight months of 2015, 30 of these mega deals were announced with a combined total deal value of more than $325 billion. This includes Shell's proposed acquisition of BG Group for approximately $70 billion (US dollars), which was made public in April 2015. This was the largest of the blockbuster deals announced that year and was the largest merger in the oil and gas industry since the famous Exxon-Mobil combination of 1998 (Table 2).

Exterran Holdings also announced a major corporate restructuring valued at about $69.3 billion in March 2015. Another was the takeover of Williams Cos. by Energy Transfer Equity, announced in May 2015 and valued at approximately $53.1 billion.

However, the mammoth Shell-BG merger was the real blockbuster of 2015. It alone accounts for some 73% of the total value of oil and gas M&A global deals announced during the second quarter (See Figure 2).

During the final three months of 2014, there were a total of 57 oil and gas deals (with values greater than $50 million) accounting for $128.7 billion, compared to 56 deals worth $43 billion in the fourth quarter of 2013, a 200% growth in total deal value. Mega deals also represented 91% of total deal value in the fourth quarter of 2014.

"While 2014 was a very strong year for oil and gas deal activity, we saw a steady decline in November and December as the drop in oil prices accelerated, contributing to a marked shift in deal sentiment from playing offense to playing defense as companies focused on maintaining liquidity," said Doug Meier, PwC's US energy sector deals leader. "That downward trajectory in oil prices, coupled with the impact of leverage, drove a number of deals related to corporate restructurings and portfolio right sizing activities. In today's low price environment, the effects of debt could drive additional deal activity as leveraged companies look to strengthen their balance sheets by focusing on cash flow optimization and operational efficiencies. PwC's Fit for $50 program assists senior management to develop programs that can enable them to withstand the current price environment and help create a platform for profitable growth as commodity prices recover."

For deals valued at more than $50 million, corporate transactions represented 16 deals totaling $103.7 billion in the fourth quarter of 2014. For the full year of 2014, there were 59 corporate transactions that contributed $227.5 billion. Asset transactions continued to dominate total M&A deal volume during the fourth quarter of 2014 with 41 deals representing 72% of total deal volume. Deal value for asset transactions reached $25 billion, accounting for 19% of total deal value for the fourth quarter of 2014. For all of 2014, there were 193 asset deals worth $94 billion.

PwC notes that during the fourth quarter of 2014, there were 15 mega deals representing $117.5 billion, compared to eight mega deals worth $26.4 billion during the same period in 2013. In all of 2014, there were 49 mega deals worth $266.1 billion, accounting for 83% of total deal value.

Foreign investors continued to show interest in the US as both deal value and volume were at 10-year highs, contributing 56 deals worth $71.2 billion in 2014. In the fourth quarter, foreign buyers announced 15 deals, accounting for $25.4 billion in value, a 25% increase in deal volume and a 426% increase in deal value compared to the same period last year. Overall deal volume and value for foreign investors in 2014 increased 75% and 468%, respectively, compared to the previous year.

There were 19 midstream deals, contributing $53 billion in value, a 111% growth in deal volume and a 276% growth in deal value compared to the fourth quarter of 2013. Upstream deals accounted for 25 transactions representing $32.5 billion. The total number of downstream deals decreased to six, while total deal value increased to $7 billion compared to nine deals worth $4.2 billion during the same period in 2013. The number of oilfield services deals remained the same at seven, while total deal value increased 619% to $36 billion - a 10-year high, compared to $5 billion in the fourth quarter of 2013.

According to PwC, there were 24 deals with values greater than $50 million related toshale plays in the fourth quarter of 2014, totaling $57 billion. This represents a 139% increase in total deal value compared to the fourth quarter of 2013. For all of 2014, there were 107 total shale deals that contributed $110.3 billion, a 107% growth in deal value when compared to full-year 2013.

In the upstream sector, shale deals represented 19 transactions and accounted for $14.9 billion, or 76% of total upstream deal volume in the fourth quarter of 2014. There were five midstream shale-related deals in the fourth quarter of 2014, accounting for $42.1 billion, or a 230% increase in deal value compared to the same period in 2013.

"Overall 2014 shale deal value and volume surpassed 2013 highlighting the continued interest from investors in US shale plays, especially in the upstream space, which contributed 79% of total shale deal activity," said John Brady, a Houston-based partner with PwC's energy practice. "However, a sustained low oil price environment is driving an intense focus on returns and the deployment of assets to the most efficient shale plays."

The most active shale plays for M&A with values greater than $50 million during the fourth quarter of 2014 include the Bakken and Permian, which each had four deals worth $3.1 billion and $2.4 billion, respectively. The Marcellus shale contributed three deals worth $5.7 billion. The Eagle Ford in Texas also contributed three deals worth $484 million, while the Niobrara and Haynesville each generated one deal.

During 2014, master limited partnerships (MLPs) were involved in 48 transactions, representing about 19% of total 2014 deal activity, consistent with recent historical levels.

Although financial investor deal activity dropped, they continued to show interest in the oil and gas industry with four total transactions, accounting for $2 billion during the fourth quarter of 2014, compared to nine deals worth $10 billion during the same period in 2013.

"In the second half of 2014, we saw financial investors remain active in assessing deal activity across the value chain," said Rob McCeney, PwC US energy and infrastructure deals partner. "If the price of oil continues to drop or remains at its current levels for a sustained period, we may see financial investors look to actively manage portfolio investments and search for new opportunities with distressed assets."

Geographically, petroleum-related M&A activity is concentrated mostly in the USA, which accounted for two-thirds of such deals' total value of in 2014 (Figure 3).

In its turn, sectorally, the bulk of petroleum-related M&A deals is concluded in upstream sector, with downstream being the least typical of such deals (Figure 4).

As for deal size, the most common in 2014 were M&A deals with value less than $10 million, which accounted for nearly one-third of reported global value. But an average size of O&G M&A deals tends to rise and has reached, according to Ernst & Young, some $450 million in 2014 compared to $270 million in 2010.

There is a known relationship between the price of oil and M&A activity. Generally, the higher the price, the more M&A deals are concluded (Figure 6), although relatively more reserves deals (deals aimed at acquiring oil and gas reserves) naturally occur in periods of low oil and gas prices, when the reserves are correspondingly cheaper to acquire.

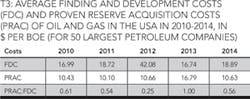

The real reason for M&A activity (for, at least, reserves deals) is rooted deeper - in relation to finding and development costs of oil and gas, on the one hand, and the reserve acquisition costs, on the other. Thus, according to Ernst & Young, finding and development costs of oil and gas in the US have risen, on average, from less than $17 per boe in 2010 to more than $42 and then fallen to nearly $19/boe in 2014, while proved reserve acquisition costs - from more than $10.4/boe in 2010 up to nearly $16.8 in 2013 and down to over $10.6/boe in 2014.

It is noteworthy that the cost of reserves acquisition for the entire period were lower than the cost to find and develop reserves (Table 3 and Figure 7).

Reserves acquisition costs for different oil- and gas-producing areas are quite different, with the lowest ones in the world being usually assumed for the FSU/CIS. Reflecting the poor investment climate in the Russian petroleum industry, further decreased in the last years, they are now around $2.5/boe. Thus, in early 2015 government proposals to sell 19.5% of shares of the leading Russian oil producer, Rosneft, these costs would be (if the plans would materialize) less than $2.54/boe compared to some $3.72/boe, for which a bit more than 1.42% of the company's shares (and total proved reserves) was sold in mid-2006 to UK's BP within the last privatization of Rosneft (14.8%), including Malaysia's Petronas, China's CNPC, and some 140,000 Russian citizens.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eugene M. Khartukov is Professor of Economics at the Moscow State University for International Relations, general director of the Center for Petroleum Business Studies, chief of the World Energy Analysis & Forecasting Group, and vice president (for Eurasia) of Petro-Logistics SA. Prof. Khartukov is an international expert on Russian and ex-Soviet oil and gas issues. Since 1980, he has taught world oil and energy markets research at Moscow State University for International Relations. Since 1984, he has consulted on oil and gas economics and policies, including energy pricing, to various Soviet/Russian ministries, international agencies, foreign governments, private oil and gas companies, consulting firms and financial institutions, as well as to the Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Putin administrations. He can be reached at [email protected].