Managing the capital cycle

Cyclical oil and gas industry requires adaptability by industry participants

James Constas, EnerCom Inc., Denver

View Image Gallery>>

Capital in the oil and gas industry can be likened to water, in that it flows from markets to companies and is then invested into finding and developing resources. Water is energy and just over 100 years ago river resources were harnessed to power sawmills and grain mills. Water is still required to grow food, of course, and irrigation remains a key ingredient in feeding six billion hungry mouths in the modern world.

Today, those mills are powered by electricity, some of which is generated by hydroelectric dams, but increasingly more likely created by natural gas-burning generators. Water follows its own cycle, and so does capital. If water seeks the lowest point driven by gravity, then capital allocated by managers seeks the highest returns, and generates more value (i.e., return on capital) that can be reinvested into more projects, perpetuating the cycle, so long as there is demand for the resource. Perhaps in no other industry than oil and gas is the capital cycle on full display.

Since 2008, a river of capital has flowed into the upstream sector of the North American oil and gas industry. One large boulder that fell into this metaphorical river, however, was OPEC's 2014 "Thanksgiving Day Turkey Surprise" in which swing producer Saudi Arabia decided against cutting crude production, even symbolically, to defend oil prices. Foreshadowing Saudi Arabia's thinking about crude oil prices, on Feb. 4, 2011, Saudi Arabian Oil Minister Ali Al-Naimi said prices nearer $75 would be "appropriate." On Feb. 3, 2011, Brent was at US$103.37 in intra-day trading. Brent closed at US$55.91 on Mar. 8, 2015.

Proving that sometimes doing nothing is an act in itself, the futures markets took the November 27, 2014, OPEC non-decision as confirmation that oil markets were oversupplied, which led to the current environment of weak commodity prices. West Texas Intermediate, the primary North American crude benchmark, closed at $48.84 per barrel on March 13, 2015, 54% lower than the same time last year.

The crude oil price drop has disrupted the flow of funds to projects worldwide and resulting in significant losses of jobs and value. At Mar. 13, 2015, the market value of US independents was $144.8 billion lower than the same time last year, a stunning 25% loss of value for a 78-company subset of EnerCom's E&P database. The stock prices of only six E&Ps rose during the 12-month period, and the magnitude of losses ranged from a low of minus 3.8% to a high of minus 91.9%.

The action of one country making unilateral policy for one global commodity has produced profound effects on an entire industry, not to mention government receipts, employment, and consumer spending. If we needed any reminder that we live in a global village, the action of one country has indeed impacted the entire world.

The reaction to the new price environment has been swift and decisive. On Friday, Mar. 13, 2015, the Baker-Hughes oil rig count stood at 866, a 56-rig drop from the previous week and 595 lower than the same time last year, equivalent to a 41% decline. We have to look back to Oct. 2, 2009, to find the oil rig count at current levels, and then WTI was $107.94 per barrel.

From a purely rational economic point of view, the industry has reacted exactly as an economist would have predicted. As price-takers, oil and natural gas producers have little to no control over the price of their products. Falling commodity prices are tantamount to transforming a life-giving rain shower capable of recharging the river of capital into a light drizzle, insufficient for generating funds for reinvestment and eroding the returns on development drilling.

As a client CEO said to us in San Francisco during EnerCom's The Oil & Services Conference, "This isn't a cycle. This is a steamroller that just hit us."

Looking back at the 12-month forward-curve for crude oil prices (WTI) starting in January over the past five years, the forward curve has been in some form of backwardation (excluding geo-political spikes) between 2012 and 2015. Starting around the beginning of January 2015, the curve was in contango, and CFOs could lock in higher future oil prices tomorrow than at spot prices today.

In the current environment, management teams have substantially cut capital allocated to drill and pivoted towards capital preservation for enduring this current down cycle. In this article, we examine what management teams are doing to achieve these goals and share some observations on the cycle of conserving, raising, allocating, and generating capital in the upstream sector.

View Image Gallery>>

The silent thief

Inflation has often been called "the silent thief," to describe the pernicious effect of rising prices on household budgets, especially those on fixed incomes. In the oil and gas business, resource depletion is the silent thief that works against corporate growth goals.

In many ways, the upstream business behaves like the car business. We have all been seduced by the aroma of "new car smell," that alluring combination of aromas from new plastic, supple leather seats, and fresh carpet. Combined with an exterior free of parking lot dings and paint chips on the outside and a Blaupunkt premium sound system that makes us feel like we are listening to Pavarotti at Carnegie Hall on the inside, suddenly we're hooked! Once we drive off the lot, our rolling opera house instantly loses 20% of its value. In two years, we will be fortunate if our vehicle loses only 30% of what we paid on the showroom floor.

Since most unconventional wells drilled in North American resource plays will produce about 30% of their total estimated recovery within the first two years, suddenly a 20% depreciation hit on a new car doesn't sound all that bad. In fact, EnerCom's well economics model for the "typical" Bakken oil shale well forecasts a 65% first-year decline in the production rate and estimates total production of 220,000 barrels of oil equivalent in the first two years of its life, or about 30% of the well's total estimated ultimate recovery (EUR).

Although we write for a savvy audience, emphasizing the decline curve at the outset is important, because it is fundamental for understanding the challenges, opportunities, and risks involved in capital allocation and financing growth.

Merely holding production flat, however, is not an option for most independent E&Ps. As public companies, their mission is to grow and the target capital market for these companies is institutional growth investors, who expect management to deliver growth at an annual rate of 20% or more. Yet, the silent thief of depletion works silently and persistently against this objective.

What is a growth company?

EnerCom maintains a database containing more than 40 quarters of comprehensive operating, financial, and statistical data on more than 200 companies listed on North American, European and Asian stock markets. We perform analysis and benchmarking for clients, comparing quarterly annual and basin results against peer groups. Our hypothesis and conclusions in this paper are supported by this database and our insight gained from observations and discussions with executives, field personnel, investors, and analysts over the previous 22 years.

If growth is the mandate from the investment community to most independents, then how much growth is enough to qualify as a "growth company?" In response to questions from our clients, we researched the answer using data sourced from EnerCom's US E&P database.

Figure 1 plots three-year Debt-Adjusted Production Growth per Share, a metric that compensates nominal production growth for changes in capital structure, on the x-axis against three-year share price appreciation on the y-axis. We used the three-year period ended Dec. 31, 2013 in order to provide a long-term perspective on growth, and during a time when the market could be considered relatively efficient having a duration long enough to dampen any large swings in commodity prices. The analysis includes 23 US independent E&Ps for which we had complete data. We observed a strong relationship between debt-adjusted production growth per share and long-term share price appreciation, as evidenced by the 0.7741 R-squared value. We removed companies with international operations and those with share price changes that were driven primarily by company-specific catalysts having little to do with longer-term operational performance. Had the sample been expanded to include those companies, the R-squared statistic would have been 0.1879.

As expected, the market sold off shares of companies that experienced a decline in production, and in general bid-up the shares of those demonstrating a track record of delivering consistent growth. Based on our analysis, we estimate that the "growth company" effect begins to kick-in when annual debt-adjusted production growth reaches 20% or more.

View Image Gallery>>

The intense thirst for capital

If the growth company threshold is approximately 20% for debt-adjusted production growth, then the question becomes what is the financing required to achieve that threshold and what is a company's ability to grow production organically?

We tracked the Asset Intensity of 74 E&P companies from EnerCom's US E&P database. Asset Intensity is the percentage of cash flow required to keep production flat, and we measure it by dividing the product of production and three-year finding and development costs by cash flow from operations, on a trailing 12-month (TTM) basis. An Asset Intensity value of less than 100% implies that a company is generating free cash flow in excess of its base decline, which can be reinvested back into organic growth. A value greater than 100% indicates a company is reliant on outside capital just to hold production on par with current levels.

At Sept. 30, 2014, the average Asset Intensity for the group was 105%, although skewed higher by a few companies, but indicating that most independents were capable of funding at least a portion of their capital plans with internally generated cash flow. However, even though 64 of the 74 companies in our sample posted Asset Intensity scores less than 100%, they still had to outspend cash flow to achieve their production growth goals.

For example, of the 74 independents in our analysis, only 13 posted positive FCF for the trailing 12 months ended Sept. 30, 2014. Simply put, growth company management teams are reliant on outside capital to fund growth plans and have had to dip into the river of capital from time to time.

Raising capital

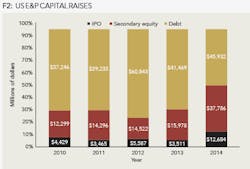

For management teams at public companies, the river of capital they can tap into includes both equity and debt, while private operators are generally dependent on some form of debt, usually secured by their proved reserves. Over the past five years, US and Canadian E&Ps have raised more than $349 billion in capital from IPOs, secondary equity offerings and debt, as illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the proportion of capital raised by type from 2010 through year-end 2014.

By far, debt has been the most popular type of capital for E&P companies to raise. There are several good reasons to employ debt rather than equity, including:

- It's non-dilutive to share count and the outflow of cash in the form of interest payments is deductible;

- Reduces the weighted average cost of capital as debt is generally less expensive than equity;

- The holders of the debt capital instrument are senior to the equity holders and will tend to hold the debt longer; and

- It's easier to raise as it provides a steady state flow of cash to the holders of the note.

Of note is that in 2014, secondary equity offerings surged to 39% of total capital raised, as compared to the average of 23% in the previous four years. We anticipate the increase was due to a variety of factors, including issuing equity for acquisitions and de-leveraging balance sheets.

View Image Gallery>>

Capital structure effects

If debt has been the most popular form of capital to raise, then how much leverage do independent E&Ps have? Figure 3 plots net debt to EBITDA for the trailing 12 months ended Sept. 30, 2014 from highest, or most leveraged, on the left to least leveraged on the right for 74 independents in our US E&P universe.

The median Net Debt to EBITDA on a TTM basis as of Sept. 30, 2014 for the companies in the group, denoted by the red horizontal line, was 2.0x with values ranging from a low of -3.2x to a high of 20.0x.

The gold bars represent those companies operating primarily in resource plays, such as the Eagle Ford shale play of South Texas, the Bakken and Three Forks plays of the Williston Basin, the Marcellus and Utica natural gas shale plays, and the Permian Basin of West Texas. We find that the majority of the resource players have below-average leverage, largely the result of high-quality assets that generate strong cash flows, above-average returns, and profitability, all of which combine to reduce the need for external financing.

Allocating capital to growth

If companies are riding on a river of capital driven by commodity prices, then capital structure plays a role in how high they may sit in the water. A highly levered company sits lower in the water, at greater risk and less maneuverable when markets get turbulent. If a team chooses to put more capital to work by levering-up the balance sheet to accelerate growth and earnings, then we should expect companies with higher debt levels to post above-average production growth rates.

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed a subset of 74 companies in our US E&P universe comparing their debt, as measured by Net Debt to EBITDA for the TTM ended September 30, 2014, to year-over-year production growth rates with the Median being 2.0x.

It is telling that the companies with above-median leverage grew production during the analysis perod, on average, at 25%, as compared to 42% for companies with leverage below the median. At first, this observation is counter-intuitive, and we recognize that there may be a "chicken and egg" effect here, in the sense that several of the above-average leveraged companies are non-resource players, but not all. The above median group also includes some companies that have divested assets to reduce debt.

The E&P companies with Net Debt to EBITDA below the 2.0x median include resource players drilling high-quality assets, including the Bakken/Three Forks shale oil play, the Marcellus and Utica shale gas plays, the Eagle Ford shale play in South Texas, the horizontal Niobrara play in the Colorado D-J Basin and the multi-pay, multi-play Permian Basin of West Texas.

A key observation is that asset quality appears to drive capital structure, not vice-versa.

View Image Gallery>>

Equity market reactions to capital structure

The equity market's reaction to companies with above-median leverage has been definitive. The chart below looks at the average change in equity prices for above and below median debt E&P companies in reaction to Saudi Arabia's Thanksgiving Day Surprise decision not to cut production to support world crude oil prices in 2014.

Figure 4 illustrates the average share declines from Thanksgiving Day to the market close the following Monday, Dec. 3, 2014.

Shares of independents with leverage above the median lost more value than their more lightly levered peers in every market capitalization group. Figure 5 takes a more recent, and longer-term view of the same group. For the six months ended Jan. 30, 2014, the equity prices of E&Ps with debt to EBITDA greater than the 2.0x median suffered substantially more than those with below median leverage.

Putting it in perspective, companies with net debt to EBITDA above the median of 2.0x experienced share price declines almost twice as severe as those with below median debt. In our view, there are several reasons for the selloff of leveraged companies:

- Greater financial risk, and in some cases, perceived financial distress as cash flows compressed by weakened commodity prices put the ability to service debt in doubt;

- Growth expectations reduced lower than those of companies with low, or no, debt, as interest payments eat into shrinking discretionary cash flow; and

- In the event of a default, less equity available for distribution to shareholders.

Make no mistake that companies with below-average leverage have experienced a bumpy ride, but they have been able to navigate more effectively through the rapids of the dynamic commodity price environment.

Capital allocation - well economics

E&P equity prices have fallen along with commodity prices, and so have the economics of drilling in the US. The Figure 6 illustrates the internal rates of return (IRR) for drilling in eight of America's known resource plays at three different price decks (assuming no change do drilling costs).

In August 2014 with the near-month futures price for WTI at $95.57 per barrel and natural gas of $3.89 per MMbtu, most US oil plays generated strong returns above the costs of capital for most E&P companies. As prices deteriorated into the fall, so did returns on drilling, as illustrated by the drop in IRRs at the $74.34 per barrel price level. At prevailing rates of $50 per barrel, the economics of drilling in nearly every resource play in America are stressed below the prevailing cost of capital.

As previously noted, the industry's response to the realities of the new price environment and severely deteriorated well economics has been nothing short of dramatic. Operators moved quickly to stand down rigs across the North American oil patch, dropping the Baker Hughes rig count to levels not seen since the third quarter of 2010.

Of course, there are two sides to drilling economics - commodity prices and costs. At prevailing commodity prices and capital expenditure levels, the economics of drilling in most plays do not merit the allocation of additional capital. So, we analyzed how far drilling and completion costs must decline to induce operators to stand-up rigs and drill.

Figure 7 illustrates the drilling and completion costs for the same resource plays noted above required to generate a 20% IRR.

Keen observers will note that the largest drops in required drilling and completion costs occur in oil plays. Our models estimate that capital costs for drilling and completion have to fall 41%, 52% and 66% in the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford Shale and Bakken oil shale plays, respectively. We note that this analysis is based on public company data, represents a broad range of data points and is not necessarily representative of results for an individual company or a specific well. In other words, your mileage may vary, depending on how the data is used and we update this analysis as market conditions change.

View Image Gallery>>

Capital structured to endure

When the down cycle comes, an E&P company's capital structure and its ability to endure the cycle take center stage. One of the unique features of the oil and gas business is that the value of an E&P company's most important assets - oil and gas reserves - fluctuate daily with commodity prices, but the amount of debt on the balance sheet stays the same and must be repaid in full.

To cope with compressed margins, lower free cash flow and wounded drilling economics, operators have cut capital spending in 2015 from 2014 levels. Figure 8 illustrates announced 2015 capital budgets compared to estimated 2014 spending levels (either based on guidance or analyst estimates).

From left to right in Figure 8, companies are ranked by largest capital expenditure decline to the lowest (growth), as of Sept. 30, 2014 and proforma for material capital raises before year-end. The impact of leverage is apparent. Companies with announced capital budget cuts greater than 40% have debt to EBITDA ratios of 3.2x on average, as compared to 1.7x for those E&P companies with announced reductions of less than 40% and in two cases even a slight uptick in spending.

Even with dramatic reductions in capital expenditures, operators still report they will grow production in 2015. Wells drilled in 2014 but not yet completed are likely to be placed on production in the first half of the year, while those wells that produced a partial year in 2014 will show a full year of production in 2015. Combined, these factors will drive production increases, although the rate of growth should decline.

We also note that at current oil price levels, it is still profitable to produce in most major oil plays. The average operating expense and overhead costs for the 87 companies in the US E&P subset of our database was $22.37 per barrel of oil equivalent at Sept. 30, 2014. Even at $45 per barrel, most operators are generating positive cash flow from operations.

Let's talk about the decision to allocate capital to drill new wells versus producing wells, given profitable operations. Calculating the go-forward internal rate of return on an established, producing well (after classifying the initial capital for drilling and completion as a sunk cost) is quite different, or superior, to that of drilling a new well with flush production. Therefore, producers are not really incentivized to shut-in production from profitable wells. Rather, they are highly incentivized to keep the values open and invest capital to enhance or maintain production and improve operational efficiencies, because companies have G&A burden (overhead), financing burden (interest and principle), and stock market burden (stock price) to cover.

View Image Gallery>>

The bonds that tie

Investors are very aware of the new microeconomic realities imposed on E&P companies by the macroeconomic environment. Not only have equity valuations fallen, but refinancing debt for many E&Ps has become more expensive.

From 2010 through year-end 2014, the yields on higher-quality bonds have steadily declined, along with the general trend in interest rates. In the fourth quarter, however, yields on lower quality paper having an S&P rating of B or CCC, skyrocketed. A sample of CCC rated bonds issued by independent E&Ps rose to approximately 15% at year-end 2014, up from about 7.0% only two months previous.

The river of capital continues to flow, and we note that approximately $3.4 billion of corporate bonds for independents reach maturity during 2015, and lower quality credits may find refinancing substantially more expensive in today's market than they may have anticipated.

Borrowing base redeterminations

Revolving credit facilities are another capital source, and as spring approaches, CFOs and bankers alike are thinking about this year's first round of borrowing base redeterminations. On average, 50 E&P companies in EnerCom's US E&P database have drawn down only 24% of their availability. However, that average masks the fact that several of companies are close to fully drawn. Depending on their year-end 2014 reserves report and the lending bank price deck, they could find themselves in the difficult position of having to cut capital spending further, sell their hedge book to pay down a reduced borrowing base, and/or renegotiate covenants.

The strong get stronger - tapping the equity markets

Although we cannot avoid covering some of the negative impacts of the current down cycle, there is some sunlight shining through the storm clouds. Several independents recently have tapped equity markets to shore-up their balance sheets and strengthen their competitive positions, and found a warm reception from investors.

We evaluated eight secondary equity deals that collectively raised $3.95 billion of fresh capital for their issuers. All of the announcements indicated that among other uses, the proceeds would be used to pay down outstanding indebtedness. In addition, several of the new equity issuers mentioned they planned to use their revitalized financial strength to take advantage of the current cycle and consider acquisition opportunities.

Ordinarily, we would expect an equity offering announcement to result in a reduction in share price, to account for the dilution of ownership resulting from the additional shares, at least in the short run. Apparently, these are not ordinary times, as we did not observe share price declines in proportion to the dilution impact, and in a few cases we observed the opposite.

Figure 9 compares the six-day equity price change for the independents in our analysis to the dilution percentage, as measured by the number of new shares divided by existing shares outstanding at Sept. 30, 2014. As a rule of thumb we use a six-day period covering the three days before and after an announcement, to measure the impact of news on a company's share price. This duration helps us control for market trends outside the control of management, such as commodity prices and other "noise," and events occurring outside the impact period. The companies are ranked left to right by positive to negative share price change.

The average equity dilution for the secondary offerings we analyzed was 19%, ranging from a low of 6.8% to a high of 33%. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the average six-day equity market reaction to the equity raises was a positive 1%, ranging from a high of positive 23% to a low of negative 20%.

For those companies perceived to have strong operations, expansion opportunities and good operational performance, investors appeared to view the new equity capital as a catalyst for getting stronger.

It is important to note that nothing in our business is static. Since we last looked at the equity issuers in early March, the shares of all E&P companies have declined along with further commodity price weakness. The change in share prices illustrates the impact of further declines in commodity prices since the equity offerings were closed. If we needed any reminder, no matter how good a management team or its assets, the prices of oil and gas company stocks rise and fall on the global tide of commodity prices.

View Image Gallery>>

Nearing the bottom?

There may be several reasons for the market not selling off the shares of companies raising equity in the current environment to several factors, including:

At this point in the cycle, those investors who wanted to trim or eliminate their exposure to oil and gas names have already done so. In other words, the panic and fear money is gone.

Short sellers have made their money, and after a 50%+ decline in oil and gas valuations, they may have less interest in betting on additional weakness.

Bargain hunters abound. As we reported at EnerCom's conference in San Francisco in February, 76% of respondents to our survey of the West Coast buy-side indicated they were in "bargain hunting" mode, looking for opportunities to stock-up on their favorite names at discount prices, providing willing buyers to those looking to rotate out of the sector.

Combined, the above factors may have helped to create support for oil stocks before the most recent dip in oil prices this month, and no one minimizes the potential for commodity prices to go lower before they go higher. However, we do note a split on broad investor sentiment on the future direction of oil and gas prices.

For example, respondents to our West Coast buy-side survey conducted in February 2015 were nearly evenly divided on oil prices. 52% of respondents expected oil prices to rebound to the $70 to $85 per barrel range and 43% expected continued trading in the $40 to $50 per barrel range. Only 5% believed prices would fall from prevailing levels. It bears mentioning that no one anticipated a return to $100 oil in the next 12 months.

With 95% of the market believing oil prices are at or near a bottom, oil and gas equity investors decided now was the time to put more equity into their favorite names. We anticipate more companies will consider tapping the equity river of capital in 2015.

Oil and gas is (still) a sunrise industry

When the sea changes, investors want a steady hand on the helm of the corporate ship. Those teams with experience managing through the cycles have an edge, a portfolio of high-quality assets certainly helps make things easier and a conservative capital structure helps improve a team's ability to navigate turbulent markets. Over the past 14 quarters, public E&Ps have raised more than $100 billion in new equity and debt capital, and if past is prologue, the best future performers will be those who have been able to manage the capital cycle to generate profitable growth and strategic advantage.

We are mindful that within every cycle are planted the seeds of its own destruction. Although the down cycle initiated by the Saudi grab for market share has brought with it much upheaval to much of the rest of the world's oil producing nations, including America, we note that the longer term trends appear to be working towards a rebalancing of supply and demand in the future.

As middle classes in developing nations grow and prosper, we anticipate that they will want to live a more energy-intensive lifestyle, which includes central air conditioning, maybe central heating too, and they will want a diet consisting of more protein and drive or use more public transportation. Simply put, a growing number of humanity will be living more materially prosperous and healthier lifestyles that necessarily consume more energy, and oil and natural gas are simply the most cost-efficient energy sources to deliver on that need.

In our view, oil and gas remains a sunrise industry, and this cycle, too, shall pass like all the others. The market will eventually find its equilibrium, and the river of capital will continue to flow into and through this current down cycle. Those management teams able to adapt to changing circumstances and wisely conserve, raise, allocate, and generate capital are those most likely to profit from the current down cycle and see the dawn of the next up cycle sooner than others.

View Image Gallery>>

About the authors

James Constas, managing director at EnerCom Inc., has more than 23 years of professional experience, primarily in oil and gas, in consulting, management, marketing, finance, economics and investor relations. He received his BS in International Management from Arizona State University and an MBA in Finance from the University of Denver. He is a member of the National Association of Petroleum Investment Analysts.