Staffing strategies for large projects must tackle many diverse issues

David A. Wood, DWA Energy Limited, UK

Greg Lamberson, International Construction Consulting LLC, USA

Saeid Mokhatab, Independent Consultant, Canada

Project execution of oil and gas facilities construction projects requires consideration and integration of many factors. Key considerations are staffing issues, both for the construction site and for long-term facility operations. All facilities projects share numerous planning and execution similarities. Identifying these shared project principles and addressing their effect on staffing, team performance and longer term employment helps optimize the effect of this tool.

Generic issues that affect all facilities construction projects are: safety and environmental standards, community impacts, site staffing plan, contract type, and contracting strategies, potential synergies with existing projects and facilities, geography, scope of work, and key execution principles.

Although short-term and long-term staffing issues need to be addressed by the project Front-end Engineering and Design (FEED) study with project managers and site managers ideally involved at that stage to provide constructability input, the main planning for construction site staffing is best performed in parallel with detailed design and engineering following the final investment decision (FID) for a project (Figure 1). This plan should incorporate a site organization and staffing plan as well as identify key roles and responsibilities for the construction phase and how those individuals are to be held accountable for specific activities.

It is best for site managers to be responsible for nominating and vetting personnel for all construction site positions. However, staffing plans need to be part of the more comprehensive project life cycle analysis and planning process. Based upon increasing emphasis of environmental standards and community impacts it often pays project sponsors to take a triple-bottom line approach to long-term project planning and decision-making staffing strategies can play a key role in a triple bottom line project life cycle analysis.

Contract type impacts focus of staffing strategies

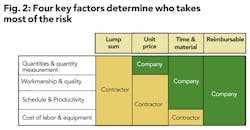

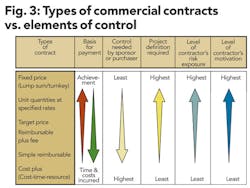

The type of construction contract directly affects site staffing. Lump sum or fixed price engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts are commonly used contracting strategies in oil and gas projects, but a range of other contract types identified in Figures 2 and 3 are also widely used.

Figure 2 identifies four key factors that are controlled by either the EPC contractor(s) or the "company" (project sponsor) depending upon the type of EPC contract adopted. The oversight required by the project sponsor will vary depending upon the contract type due to different levels of risk exposure. Do not be misled by the contractor bearing the main risks under a Lump Sum contract and assume the project sponsor has no quality, safety, schedule, and cost concerns in a lump sum (fixed price or turnkey) contract environment. A prudent project sponsor will always closely monitor performance in all projects regardless of contract type.

However, under a lump sum contract, the project sponsor's team focuses more on inspection, performance, schedule, and expediting key equipment and resources rather than motivating project staff. A typical project sponsor's site organization chart for the construction phase of an EPC contract always includes inspection, quality, and schedule personnel.

Figure 3 highlights that it is not just concerns about adjusting base staffing levels according to the type of contract to be managed, but many other issues such as the level of project definition and staff motivation are also impacted by contract type.

Contractor's organization and capabilities

When developing the construction phase site staffing plan, the contractor's site organization should be analyzed for strengths and weakness that can affect the success of the project. In some cases, it is necessary to supplement the contractor's organization with project sponsor's own personnel or specialist independent contractors. The need for these adjustments generally is not known until a vulnerability assessment is performed on the contractor. Normally this is done during the tender evaluation phase in advance of the final project investment decision and award of the main EPC contracts. Upon completion of such an assessment, project sponsor staffing adjustments should be made to supplement and leverage the contractor's weakness and strengths, respectively. This approach helps to reduce project execution risk and improve constructability performance.

Matching the contractor's organization

For project contracts where the project sponsor is bearing most of the risk exposure (e.g., reimbursable contracts), project sponsor's site teams are commonly developed and aligned to match the structure and function of the contractor's site team. On the other hand, lump sum and unit price contracts generally do not match site teams.

In offshore installation projects, regardless of contract type, project sponsor project management staff is generally structured to match the contractor's site management teams on the vessels. This is because the project sponsor has ultimate responsibility for safety and environmental impacts of most decisions taken by the contractor as a project progresses.

Project team development and motivation

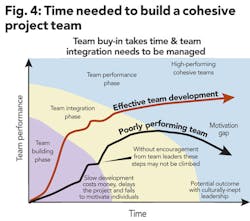

A well-disciplined and managed team can make the difference to a project. Figure 4 highlights that the time it takes to build a highly performing cohesive project team can be crucial; as time to waste is something few project teams have available. A focus on early team building initiatives can pay dividends. It is unrealistic to assemble a group of skilled staff together and expect them to perform as a team without progressing through team building and integration phases. This becomes even more important in multi-cultural teams.

Key team attributes to achieve targets by overcoming obstacles are: well-trained, highly-motivated, integrated, more collaborative than competitive, clear direction (led by focused project plan), strong leadership, shared values (buy-in/alignment), and adequately resourced.

In order to maximize team performance and individual and team motivation, the task of team building and development must be given time and priority and careful project management attention at an early phase in the execution of any significant project. This is especially the case for large and mega-scale facilities projects with activities and parallel engineering being conducted at multiple sites in several countries separated by large time differences and cultural barriers.

Project complexity

The magnitude and complexity of a project affects the organization of the project sponsor's site personnel. In many cases, the size and complexity of a project, such as a mega-project, requires splitting the project into several smaller sub-projects. In the case of sub-projects, site managers should be assigned to each sub-project along with an organization and staff resource commensurate with the work scope and contract type.

Sometimes it is the complexity of a project rather than the size of the project that demands additional staffing resources. For example, a small facility that utilizes high alloy materials might require additional specially trained welding and non-destructive examination and testing (NDE/NDT) inspectors, whereas a larger, conventional facility might employ only one welding/NDE/NDT inspector. One must assess project size and complexity, weigh the respective effects on staffing needs, and develop an effective site team that is aligned with project objectives, staffing strategies and safety/environmental standards.

Staffing synergies

Synergies for site staffing require careful review of a project sponsor's other on-going projects and looking for opportunities for sharing resources in a safe and prudent manner with a view to not only reducing the size of site teams, but also potential community benefits (e.g., retraining or redeployment of staff from projects nearing completion or the end of their operating lives). The purpose of searching out synergies is to leverage management and staff within work sites or regions where a project sponsor has other projects underway or being planned. For example, one skilled paint/coating inspector may be able to manage multiple projects as opposed to having one inspector per site or project.

Another synergy example is sharing a site safety advisor or a site quality advisor among several projects located in the same or nearby fabrication yards. Also deploying skilled staff from one project to train staff of another less experienced project team in specialist skills can lead to better performance and quality across a number of projects.

Triple bottom line issues

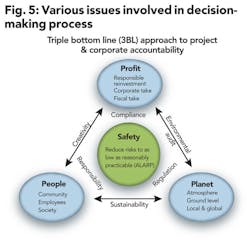

Large oil and gas companies are under increasing pressure to demonstrate that they can operate and develop projects in a sustainable and safe way. There are varying approaches to sustainability, but the more credible and accountable focus on the triple bottom line criteria (3BL) with clearly defined targets with respect to environmental and community performance (the latter including staffing issues).

Figure 5 illustrates this approach involving environmental and community issues being involved in project life cycle analysis and long-term decision making in addition to economic and profitability issues. The approach is underpinned by robust safety standards and principles that are quantified where possible in terms of risk exposures to individuals being reduced to as low as is reasonably practicable (ALARP).

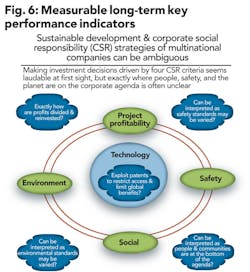

Sustainability reporting is now used quite extensively in communicating company accountability towards its broad-based stakeholders. Most sustainability reports are built around triple bottom line principles focused on (in addition to safety) three performance indicators of any company: economic (profit), social (people) and environmental (planet) performance. The social and environmental performance components of 3BL are also commonly referred to as corporate social responsibility (CSR). Unfortunately some large oil and gas companies have used CSR primarily as a public relations initiative and to make sustainability claims that are not backed up by their actions or by measurable long-term key performance indicators (Figure 6).

In this approach, for example, in some actual projects lower environmental and community standards are adopted, but justified by a company paying higher taxes or providing short-term local employment. This is poor practice and many, not just those with primarily environmental agenda's, are critical of corporate hypocrisy in this regard. Such an approach is also unlikely to result in a meaningful staffing and high standards of long-term project performance.

Triple bottom line principles linked to project life cycle analysis (i.e. benefits assessed over the construction, operations and post-project periods) with clearly quantifiable and measurable objectives to which companies can be held accountable are preferable to ambiguous and public-relations-driven CSR initiatives and platitudes.

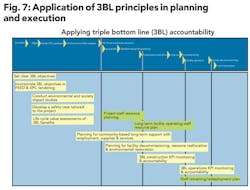

Figure 7 illustrates how such 3BL principles can be included into project planning and execution including staff planning components. It also emphasizes the need for a life cycle approach integrating issues of the operating and decommissioning phases (perhaps decades into the future) into planning of the project construction phase.

Safety cases, environmental impact statements and life cycle analysis are now key components of the decision-making and government approval process for oil and gas facilities projects around the world. These components all have staffing implications that need to be addressed in the project planning phases and throughout a project's life.

Geography impacts staffing requirements

There are four generic onshore geographical/topographical locations that present challenging environments that affect site work. These are arctic, desert, tropical, and mountainous.

The staffing must be tailored to the special requirements of the nuances of each geographic region and to the extent to which the effect can be mitigated by staff adjustments. For example, in remote locations, a full-time logistics manager may be required. In jungle areas, there might be a need for a tropical disease specialist to work site HSE manager. In arctic conditions, arctic survival, training, provision of cold-weather equipment, and emergency response could require a dedicated specialist.

Staffing sources

At the conclusion of project organizational planning, the following should be in place:

- Project organization chart

- Roles and responsibilities

- Job descriptions including accountabilities

- Staff performance measurement strategies

Once those are in place, it is time to proceed with the main staffing effort. Employment/deployment of staff for the field positions include the following general sources:

Existing company staff: Oil and gas companies have processes to identify qualified personnel within their own company. This process is often managed through a human resources department and considers the needs of the project, the career development of the individual, the long-term needs for the skills and competencies, available resources, and future workloads.

New company hires: From time to time, depending on the overall company's growth strategy, project portfolio, and departmental needs, the decision is made to hire new employees with required specialist skills and experience.

Agency staff: A common method of site staffing involves contracting qualified individuals through recruiting companies that specialize in oil and gas projects. Provisions and firewalls are made between the agency and the project sponsor to limit the liability as a "co-employer" and to protect the "contractor-status" of the individual contractors. These firewalls include the agency retaining the right of:

- Final hiring and firing

- Setting day or hourly rates and benefits

- Assigning the individual to the project

- Negotiating with the company regarding the nature and duration of work assignments, work hours, conditions, etc.

- Evaluating performance

Independent contractor: From time to time oil and gas companies use independent contractors or consultants directly. Cases to be made for this are specialty consultants that are used on an ad hoc basis. However, this is generally avoided as the cost to administer individual contracts is onerous and it is more efficient to manage a single contract with an agency for numerous individuals.

Seconded staff: An individual may be seconded to the site team from a joint venture (JV) partner, or from a national oil company (NOC) depending on the type of production agreement in place. Seconded individuals typically continue to be employed by their company or NOC, but take their day-to-day direction from the site manager or project supervisor.

Utilizing staffing templates

Many major oil and gas companies have developed a suite of templates or check lists to address organizational models that cover all of their potential projects. These "models" are developed as "go-bys" to provide a starting place for the site manager. From the templates, the organization and staff plan are developed considering the contracting type, contractor organization, and the various nuances discussed previously.

Typically these templates include all positions that report to the site manager and identify which positions are targeted to be filled by employees rather than contractors. A robust template system should also include job titles and reporting structure as well as detailed job descriptions and accountabilities.

De-staffing, long-term planning and community implications

An often overlooked aspect is the demobilization of staff or "de-staffing" once certain phases of a project are completed. This should be addressed with the same level of thought and detail as the staffing plan. Studies have shown on large projects that negative impacts of ineffective de-staffing (either too early or too late or with little regard for wider community impacts) can increase overall project costs, delay a project's schedule, negatively impact staff and team morale and lead to a deterioration in community relations.

Towards the end of the construction phase of a project it is common to experience both planned and unplanned transition of people. Key project positions must be maintained as much as practicable and when possible potential replacement candidates identified and developed early in the project cycle.

Conclusions

- Effective project planning and execution requires detailed short-term and long-term staffing plans and strategies.

- Active and early engagement of site managers and their involvement in early site planning efforts is essential to ensure appropriately resourced and motivated project teams.

- By having an early, effective, and a systematic approach to site planning, a higher level of input and influence can be achieved.

- Careful integration of triple bottom line principles into project planning and staffing strategies are more likely to achieve projects with long-term sustainable outcomes for the communities in which they are developed.

- One of the significant principles of successful projects lies in staff planning and team building in order to utilize the best available resources in the most efficient and optimum way.

By assembling the right staff into a project team, motivating that team and the local community, complex long-term projects are more resilient in overcoming a multitude of issues and problems.

About the authors

David Wood is the principal consultant of DWA Energy Limited, UK, specializing in the integration of technical, economic, risk and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and project management decisions. He has more than 30 years of international oil and gas experience spanning technical and commercial operations, contract evaluation and senior corporate management. Industry experience includes Phillips Petroleum, Amoco, and Canadian independents including three years in Colombia and four years in Dubai. He is based in Lincoln, UK.

Greg Lamberson is the principal consultant of International Construction Consulting LLC, USA, with over 25 years experience in all phases of the business, project, engineering, and construction management for upstream and midstream oil, gas, products, and energy-related facilities, including pipelines.

Saeid Mokhatab is a technical advisor for various companies and research organizations in the upstream and downstream energy sectors on a domestic and international basis. He has participated in several international gas-engineering projects and published more than 200 technical papers and magazine articles.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com