Uncertainty surrounds Russia-to-Europe gas agreements

Europe needs Russian gas, but EU members can expect changes in long-term contracts, on-border trade, and destination clauses.

Dr. Andrei Konoplyanik, Energy Charter SecretariatBrussels, Belgium

Europe will remain strongly dependent on external energy - in particular, gas supplies - for at least the next few decades. At present, imported gas accounts for around 40% of consumption. According to European Union (EU) estimates, total energy imports will rise to about 70% of total energy usage in Europe between 2020 and 2030, and imported natural gas may increase to as much as 90% of European consumption.

Among natural gas suppliers, Russia has been and will continue to be the primary source for Europe’s energy needs. Forty percent of gas imports come from Russia, and this dependence is not likely to change in the foreseeable future.

By 2020, Russia will provide Europe with around 250 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas, which is equal to about half of all imports (estimated at 525 bcm). Looking forward, of the 525 bcm, 400 bcm are not yet contracted, including the bulk of prospective imports from Russia.

A key question, which I will address here, is: What would be the new contractual terms for these not-yet-contracted supplies? This will be of crucial importance both for the exporters and importers.

Energy markets evolving

Historically, Russia and its predecessor, the USSR, have been a reliable trade partner for the EU. Despite difficulties at various times, both governmental entities always fulfilled their supply obligations under their long-term contracts with the EU. However, just as global energy markets have not remained fixed, the structure of international energy contracts has been evolving as well.

The present structure of Russia-to-Europe gas contracts reflects the realities of the past. Since the existing contracts were signed, governments have changed, new policies have emerged, and energy markets have opened up to the private sector. Newly structured gas contracts are inevitable.

Undoubtedly new gas contracts will reflect these changes in market structures. It is to be hoped that they also balance the interests of both the producers (exporters) and consumers (importers). Where such contractual changes generate incremental risk within one or more segments of the gas value chain, those risks would need to be addressed and redistributed among all the players involved.

One of the hot-button issues being debated with regard to these contracts is the problem of the so-called “destination clauses” (territorial sales restrictions). These provisions are an integral part of existing Russian gas export contracts, but are strongly objected to by the EU Commission as violating its competition laws. For some time, the EU has demanded a forced removal of destination clauses from all existing import gas contracts with Russia, Algeria, and Norway.

In 2001, after significant debate on the issue, Russia and Gazprom (the Russian gas giant) agreed to changes in contracts related to gas supplies to Italy and Austria. Negotiations are still underway with Germany. However, the issue of destination clauses is far from solved because the problem is deeper than it appears at first glance.

There are three groups of issues related to Russian gas supplies to Europe:

1) How they have been organized and why so;

2) Whether and how they are being reorganized and why so;

3) Whether current changes balance the interests of exporters and importers.

What we must do is find a balanced solution in keeping with current market realities in order to assure secure and effective gas supplies to Europe within the yet-uncontracted supplies.

Major elements of Russian gas exports

There are four major characteristic features with regard to Russian gas exports to Europe:

• Long-term “take and/or pay” contracts (LTC TOP);

• On-border (on external border of EU-15) sales;

• “Destination clauses” (territorial sales restrictions); and

• Key role of transit (both in physical and contractual terms).

This system reflects historical balance of interests in the organization of gas trade between exporters (USSR/Russia) and importers (Europe/EU). Destination clauses present only one integral element in this package and thus are subject to the so-called “matrix effect” known from elementary mathematics: when one element in the matrix is changed, that leads to corresponding changes of the sums in the respective rows and columns and of the sum-total of the whole matrix, which in turn results in the establishment of a new balance within the matrix. Consequently, the change of only one element leads to changes in the whole picture and, in this case, a new balance of interests.

Long-term contracts

Current organization of Russia’s gas supplies to Europe is the result of investment decisions taken some decades ago during the Soviet era. In the 1970s, the United States had established an embargo on certain supplies to the Soviet Union after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. However, several European countries anxious to receive gas supplies from the USSR agreed to supply pipes and compressor stations to complete the needed pipeline infrastructure. Those European contractors - mostly from West Germany, Italy, and France - were to be compensated by supplies of Soviet gas.

The contractual structure of those deals was based on “take and/or pay” contracts that were needed to guarantee long-term flow of revenues to pay back the cost of credits and supplies received for project development.

The take and/or pay contract is a financial tool demanded by the financial community (banks and other institutions). They serve the buyers’ geographic market area on an exclusive (monopoly) basis. The seller assumes reservoir and delivery risk, while the buyer assumes market risk.

Since the 1970s, due to natural developments in international energy and financial markets, there has been a clear shift from equity financing to debt financing as a dominant means of raising the capital for development of new oil and gas projects. Since that time, more and more oil and gas investment projects has been developed under project financing instruments, especially in the upstream sector.

Volume and value (cost) of financing is dependent on future revenues and risks related to those revenue streams. Revenue flow is a function (product) of the volume of supplies multiplied at the price of the commodity and thus is dependent on volume and price risks.

On the one hand, LTC TOP is an effective mechanism of supply risk (volume risk) reduction, since it guarantees the volume of commodity to be supplied during the contractual period. On the other hand, LTC TOP plus an adequate pricing mechanism incorporated into such a contract presents an effective means of reducing price risk.

In the first half of the twentieth century, at the early stages of the development of energy markets, LTC TOP was an integral trade part of the concessions and production-sharing agreements (PSAs) that were the dominant financial/investment instrument for the development of upstream projects in oil and gas. That was the period of absolute dominance of long-term contracts.

The prices in LTC TOP at that time were usually fixed for the entire duration of the contract because it was a period of relatively stable oil prices and fixed exchange rates (i.e., prior to the establishment of the floating US dollar exchange rate).

Since the late 1970s and early 1980s and prior to the period of exchange pricing (spot/futures), the pricing mechanism for gas began to change. Within contemporary long-term contracts, the gas price is a formula price and is based on the so-called “escalation” formulas that tie down gas prices to the prices of other primary energy resources competing with gas in a given market in a given end-user sector.

For example, if Russian gas is supplied to German power plants, then its price may be tied to the prices for coal and residual fuel oil (RFO) on the German market. More frequently, gas prices are tied to exchange quotations for RFO and crude oil, which often hinge on global expectations of the world oil market.

With exchange pricing, the pricing mechanism of LTC TOP is decoupled from the escalation formula and is based on a combination of spot/futures/options with hedging instruments. But long-term contracts as such would continue to exist until the risks related to being a party to them does not exceed the risks related to being a party to a shorter-term contract.

By effectively reducing both volume and price risk, LTC TOP has become an effective financial instrument for new upstream (production and transportation) project development. It reduces risk in long-term, capital-intensive Greenfield upstream projects, especially in regions lacking production and transportation infrastructure. This mechanism was used for financing the major routes of Soviet (now Russian) gas supplies to Europe in the 1970s (the southern pipeline through Ukraine) and 1980s (the northern route through Belarus).

LTCs within the EU market

Long-term contracts (see Table 1) are not only a major feature of Russian gas supplies to Europe, but the European gas market itself has been developing based on long-term gas supply contracts, which form a core element of domestic European gas supplies as well. More than 90 percent of all gas imports use LTC, and this will continue to be an integral part of the EU gas market for the foreseeable future.

Oddly, the European Commission has long argued against long-term contracts as preventing competition. However, the commission has finally agreed with the important role of LTC TOP in gas supplies, stating that such contracts do not undermine the objectives of the commission and are compatible with the 1958 Treaty of Rome with regard to competition.

On-border trade

Two major export pipelines run from Western Siberia to Europe (see Fig. 1). The southern pipeline runs through Ukraine and then Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The northern pipeline transits Belarus and then Poland. The Russian gas is exported to the EU under long-term contracts that provide for delivery points along the EU-15 external border (the eastern borders of the EU prior to its May 2004 expansion).

The USSR signed its long-term contracts with European companies during the Cold War period in a very different political atmosphere from today. At the various delivery points, ownership of the gas changed hands when it left Soviet or Eastern European hands, so the new owner then assumed delivery risk.

Since the collapse of the USSR, Gazprom, the quasi-state-run company, has taken responsibility for the gas supplies within the route from Western Siberia and up to the delivery points at the EU-15 border. Western companies take responsibility from those delivery points up to the consumers of the gas.

Although the political situation in Europe has changed dramatically since the early 1990s, the delivery points have remained the same as they were in the Soviet era. That means that after EU expansion took place in 2004, the main delivery points for Russian gas into Europe have “moved” inside the EU area. The EU now has 25 member states - not the 15 members it formerly had.

At Point B in Fig. 1, only the title of ownership for the pipeline is changed. It is transferred from the companies of the corresponding CIS states to the companies of the corresponding new EU states, but Gazprom still owns the gas being shipped through the pipes. However, at Point C, both the title of ownership for the pipeline and the ownership of the gas within the pipeline is transferred to the corresponding European companies.

EU expansion has established a new reality in the Russian gas trade with Europe: Russian-owned gas has been trading within the EU. Several issues need to be clarified, including whether this situation has generated new risks for any of the contracting parties. If so, what are the risks? And how is it possible to secure, prevent, or spread those risks among the various participants?

Destination clauses

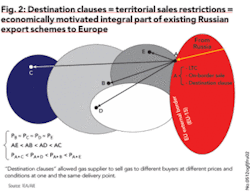

Territorial sales restrictions, also known as destination clauses, are an integral part of existing Russian export schemes to Europe. The clauses allow the supplier to sell gas to different buyers at different prices and conditions at the same delivery point. The destination clauses restrict onward sales and limit the use of gas sales to a contractually-specified geographic market area.

Fig. 2 illustrates the economic background of destination clauses, which have been an instrument for reducing market risk. The clauses, which are economically motivated, prohibit the importer from reselling the gas to another importer at a more distant point. Fig. 3 depicts how destination clauses are applied, providing an example of Russian gas imported at Baumgarten in Austria and showing the Austrian, French, and Italian prices.

Destination clauses prevent, for example, a French buyer of Russian gas from reselling it in, say, Austria or Italy and thus receiving a windfall profit (or undue benefit) by taking advantage of the price differentials among the various destinations for the gas.

At present, the Commission on European Communities has been trying to deal with destination clauses on a case-by-case basis.

Poll of conference attendees on gas

At the March 2004 FLAME Conference (perhaps the most important gas event within the EU), a polling session took place that aimed to provide an expert view of the European gas community at present and the prospects for market development. Around 250 conference attendees participated in the poll. Here are some of the results:

• Asked how they would characterize Europe’s gas market in 10 years, 64% of the respondents answered, “dominated by a few fully integrated energy companies,” while 15% said, “dominated by a few large international gas buyers.”

• For the question, “When do you believe that European long-term contract gas prices will become decoupled from oil and determined by spot/futures prices?” - 24% said before the end of 2010; 36% answered before the end of 2015; and 24% said never.

• Asked what will be the volume of gas sold at hubs as a percentage of total EU gas sales in 2008, 35% said 6% to 10% and 37% said 11% to 20%.

• Finally, for the question, “Why do you think that traded markets across Europe lack liquidity?” - 41% of respondents said “access to pipeline capacity” and 30 said “refusal of major companies to participate significantly.”

The poll results clearly show that the participants do not believe market liberalization will come quickly. Rather, they believe that for the next five to 10 years it will continue to be monopolized by a few international (Western) energy companies and that access to pipeline capacities will continue to be a major problem.

Transit

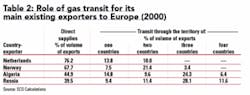

For Russia, the issue of transit of its energy supplies is probably more important than for any other energy exporter, including those countries that are competing with Russia in Europe - especially in gas. A significant portion of Russian gas has to pass through two or more countries to reach its destination. Table 2 shows the role of gas transit for the main suppliers of gas to Europe. This illustrates why transit issues and ECT Transit Protocol are a major concern to Russia.

In legal terms, there are three different options of carrying out supplies of energy materials and products (EMP) from the territory of one contracting party to the territory of another contracting party.

The first option is no transit at all. In this case, on-border sales take place at delivery points C and D in Fig. 4. Recent long-term gas supply agreements of Russia with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan have been based on on-border sales terms as well. Furthermore, on-border sales are not limited to Russian supply contracts to Europe. They are also an integral part of, say, the Algerian supply schemes to Italy and Spain.

The second option is transit through the pipe that is owned or leased by the shipper. Under this scheme, gas originating in Russia and destined to France is shipped by Gaz de France from the delivery point through Germany to the French border. Similarly, gas destined for Italy is shipped by ENI via Austria through the TAG pipeline partly owned by ENI. Similar schemes are used in supplies of Norwegian gas to France. Gazprom has been attempting to purchase stock in some of the pipeline companies that historically are involved in the transmission of Russian gas supplies to Europe.

The third option is transit through a pipe that is not owned by the shipper. That is the case for the Energy Charter Transit Protocol, which means that its finalization would not prohibit all the other ways and means of carrying supplies from Point A to Point B (see Fig. 4) except the transit ones, but would provide more legal guarantees because this is the cheapest way of transporting such supplies.

Energy Charter Transit Protocol

The aim of the Energy Charter Transit Protocol is to establish a clear set of inter-governmental “rules of the game” governing cross-border flows of energy in transit via pipelines and grids, building on the existing transit-related provisions of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty. Transit protocol will lower the level of political and financial risks associated with those oil and gas projects that require transit across Eurasia. This is intended to make energy supplies within the developing Eurasian market more stable and secure, diminish the cost of raising capital (equity and debt financing), increase the investment availability for upstream energy projects, and make them more competitive.

In other words, it is designed to benefit not only consumer-states, but also producer-states and transit-states.

Among the key features of the protocol are its definition of the concept of “available capacity for transit” in national pipelines and grid systems; the obligation it contains for signatory states to negotiate access to such available capacity in good faith and on a non-discriminatory basis with interested third parties; and its establishment of the rule that transit tariffs must be non-discriminatory, cost-based, and free of distortions resulting from any abuse of a dominant market position by pipeline or grid owners (see Table 3).

Fig. 4 illustrates this in some detail, and Fig. 5 provides two scenarios of Russian gas expansion farther into Europe.

Gas transit and contractual mismatch

A natural question arises: In which geographical areas does transit (legal definition) of Russian gas to Europe occur? The answer is not as simple as one might think - the distance between the external border of Russia and the external border of the EU state that is the final destination of the gas. Following this line of reasoning, all the countries between Russia and the final destination would be considered “transit states.”

After May 1, 2004, when the EU enlargement took place and 10 new member-countries entered the EU family, including the former transit states for Russian gas to Europe, the “C” delivery points (see Fig. 1) became located within the EU territory. The “B” delivery points were located at the new external border of the EU.

Why is this important? Because, according to both the original 1958 Treaty of Rome and the REIO clause in the draft Transit Protocol, there is no “transit” (again, legal definition) within the EU. Consequently, there can be no more transit supplies of Russian gas within the new EU member-states. So, from a legal perspective, no “transit” can take place between points “B” and “C” anymore.

What this means is that prior to May 1, 2004, transit states for Russian gas supplies to Europe were all the states of Zone II and III. After that date, only the states of Zone III met the definition (see Fig. 6).

The EU enlargement may have unexpected economic consequences for Russian gas transit supplies to Europe within the acting long-term contracts - in cases of mismatch between the expiration date of supply and related transit agreements.

A mismatch between the expiration dates of long-term supply (delivery) contracts and transit/transportation contracts creates a risk of non-renewal of the transit/transportation contract, especially in cases where the supply and transportation entities are legally separate business operations.

The core issue regarding the mismatch problem is a guarantee of access to transportation capacity for the shipper within the duration of the existing delivery contract (see Fig. 7).

There are two principal avenues to solve the problem of mismatch: to exclude the mismatch altogether or to use mechanisms minimizing risk related to it.

In the first case, there are two possibilities:

• to diminish the duration of supply contracts to the duration of the transit/transportation contracts; and

• to increase the duration of transit/transportation contracts to the duration of supply contracts.

In the second case, there may also be a few ways to solve the problem. One is the so-called “Right of First Refusal” (RFR), which has been proposed by the Russian delegation as a universal solution to the problem of mismatch, but has been strongly opposed by the EU as being incompatible with the EU competition laws.

As a working compromise, the EU delegation has agreed that RFR might apply only to the existing Russian supplies within ex-EU territories within the ECT member-states. But the question has been left open regarding existing or potential solutions of mismatch problems that may arise within the EU.

The mismatch problem does not only exist in theory - it exists in business practice as well. It remains a major problem that must be addressed.

Moreover, regarding the opening up of European energy markets, the commission itself has recognized that the overwhelming majority of EU member-states still have to transpose the new EU rules into national law. This applies to both electricity and natural gas markets.

The issue of access to transportation capacities within the duration of long-term supply contracts within the EU is a valid one for consideration. In this regard, some natural questions arise to which answers from the EU would be very helpful, at least for the finalization of Transit Protocol negotiations:

• Does the problem of access to transportation capacity does exist within the EU?

• Does the mismatch between duration (expiration dates) of supply contracts and transportation contracts exist within the EU?

• Is there a risk of non-renewal of transportation contracts within the duration of long-term supply contracts within the EU?

• What are the procedures for renewal of transportation contracts within the duration of long-term supply contracts (if any) within the EU?, and

• Do the procedures adequately address the risks faced by shippers and (in the case of new investments) by the financial community?

Let us hope that the corresponding answers will help both contracting parties reach a compromise solution regarding the evolving contractual structure of Russian gas supplies to Europe and that this compromise will reflect the valid long-term economic, financial, and legal concerns of both parties. A balanced solution is good for the entire Energy Charter community.

The author

Dr. Andrei Konoplyanik is deputy secretary general of The Energy Charter Secretariat in Brussels, Belgium.