Over the hill? Sell the long fat tail

Cliff Atherton, GulfStarGroup, Houston

After the Crash in 2008, I worked on several financing projects that made me think creatively about energy investments, the cash flows they offer to investors, and the nature of the liabilities that motivate financial investors to risk their capital in energy assets. One of my clients was developing a hydropower project. While the hydro project had zero fuel cost, the price of the electricity it sold was determined by the price of natural gas and coal. An equity investment in this technology offered long-term optionality on the price of natural gas, a feature that is very attractive to financial investors managing bond portfolios vulnerable to higher than expected inflation in a post-Crash world flooded with liquidity from the Federal Reserve.

The E&P business has always been capital intensive, and most industry participants own development opportunities that far exceed the capital available to them for drilling. As a result, raising capital has always been a critical success factor in the industry. Operators who were better at raising capital out-performed those who were less skilled in finance, regardless of their relative skills in finding reserves. Along the way, the industry has developed financing structures that are commonly employed and readily understood. My experience with the hydro project made me wonder whether the attractiveness of long-term options on commodity prices could be the basis for yet another financing structure that would enhance the flow of investment capital into the industry.

Almost from the beginning, E&P firms raised equity capital efficiently within the industry using the traditional third-for-a-quarter structure: one third of the investment capital for one quarter of the future cash flow. Then private equity (PE) became available to the industry. The PE model involves the use of financial leverage and a reasonably fast turnover of properties. While not all are the same, many PE investors hope to realize a three to four times cash-on-cash return or better in a three- to five-year period.

From a financial perspective, 4P reserves are assets-in-place (PDP) and real options (PUDs, Probables and Possibles). When PE firms acquire oil and gas assets, they use debt and equity to purchase a bundle of assets-in-place and real options. To assuage concerns of lenders, they normally hedge near-term commodity prices. They expect to achieve a significant multiple on their initial equity investment by first drilling and completing the best of the real options they acquired. Then they seek a relatively quick capital gain. Their investment model is not predicated on the long-term harvesting of cash flows from production.

To me, the interesting thing about the presence of PE funds as large investors in the E&P industry is that many of their limited partners are the very same investors who were interested in the long duration and positive correlation with inflation of the cash flows from the hydro project. These relatively risk-averse investors liked the prospect of a steady cash yield from long-lived assets producing nominal cash flows that would appreciate commensurately if inflation were greater than expected. If these investors found the hydro project attractive because it offered unhedged exposure to the price of hydrocarbons, then they also should be attracted to investments in oil and gas if packaged inside a long-term structure different from the third-for-a-quarter proposition used to fund drilling or the PE model used to acquire, develop, and sell properties.

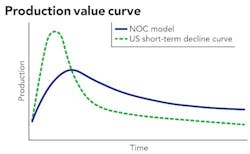

The figure on the previous page presents production curves resulting from alternative strategies for harvesting oil and gas from a known resource. The curve with the greater peak and the flatter tail is typical of the traditional approach to harvesting oil and gas from a field. In a high interest rate environment, a producer maximizes present value by producing hydrocarbons and monetizing them as quickly as possible. The curve with the flatter peak and the fatter tails typifies the long-term approach that is common among national oil companies ("NOCs"). The NOC’s objective is not to achieve some target level of IRR but to make cash available in the future to fund its country’s budget obligations which are sensitive to inflation.

Today, with interest rates at all-time lows, the penalty for deferring production is very low and may be offset by future increases in market prices for production. Today’s production is foregone future production that could be sold at higher prices. The important issue is the cost of carrying oil and gas in the ground from one period to the next. Oil in the ground is not subject to obsolescence or spoilage, so it is an attractive place for a financial investor to store value that must be carried across time before being converted into cash and spent to fund financial obligations. Because their objective is to fund future cash flows paid in nominal dollars, the flat part of the production curve may be the more attractive section, not the hump in the early years that PE firms currently pay premiums to acquire.

Want another way to think about buying the long, flat section of the production curve? Take a look at Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). Currently, their yield is negative. That’s correct, investors are willing to pay an insurance premium for inflation protection. Deferring production via the NOC approach to husbanding oil and gas assets may be a cheaper form of protection against inflation.

In today’s low-return investment environment, I believe a reasonable investment strategy for investors with long-duration liabilities is to own oil and gas reserves that have a long, relatively flat decline curve. What is the implication of this observation for owners who want to fund drilling in unconventional areas by selling older, conventional production? There is probably a better buyer for these properties than the typical private equity fund, a buyer who wants the long-term exposure to commodity price increases that would result from future inflation.

The challenge to this strategy is to develop a financial ownership structure attractive to these long-term investors. And if you can show them how to increase the oil ultimately recoverable from older, conventional reserves, then an even better bargain can be struck. Once again, the critical success factor will reward those owners who are financially sophisticated.

About the author

Cliff Atherton is an investment banker with more than 25 years of experience in corporate finance and more than 30 years’ experience teaching finance at the graduate level. He joined GulfStar in 1995 and since that time has completed numerous corporate finance assignments for business owners. Most of Atherton’s clients are entrepreneurs and family-owned businesses with enterprise values between $25 and $250 million. His transaction experience is split evenly between sales to strategic buyers and recapitalizations with private equity firms. His industry experience includes representation of upstream, midstream and downstream energy service companies and related manufacturing and distribution companies. Atherton has served full time and part time on the faculty of Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business since 1980, where he currently serves as a professor in the practice of entrepreneurship. Prior to joining GulfStar, he was managing director of McKenna & Company, the president of Emprise Consulting Group, Inc., and an independent consultant. He was also an adjunct professor of finance at the University of Houston from 1993 to 1997. Atherton earned a BA degree from Rice University and PhD and MBA degrees from the University of Texas. He also earned the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation.