How Evolving New Fuel Specs Are Challenging Asia's Refiners

Energy Security Analysis Inc.

Washington, D.C.

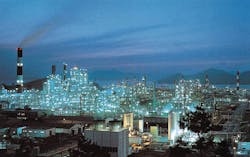

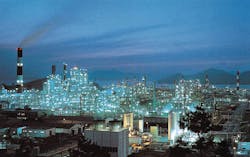

LG-Caltex Oil Corp.'s 600,000 b/d refinery at Yocheon, South Korea, is one of the world's largest. South Korea's and other Asian refiners face a complex array of challenges as growing demand for petroleum products and tightening environmental strictures dictate the scope and style of Asia's downstream expansion. Photo courtesy of Korea Petroleum Association.

- How Asia's downstream regulatory regimes are changing [64233 bytes]

- Gasoline quality in Asia in 1996 [50219 bytes]

- Asia's gasoline outlook [80536 bytes]

- Asia's diesel demand outlook [65213 bytes]

- Asian fuel oil demand by sulfur content [50024 bytes]

- Desulfurization capacity in Asia by 2000 [48846 bytes]

- Additions to Hydroprocessing capacity [35565 bytes]

Research on Asian refining capacity has focused almost exclusively on issues of quantity. A number of factors are converging to make understanding the web of issues related to the product quality imperative. Understanding the drivers and the likely path of rapidly evolving oil product specifications will be critical to the success or failure of oil producers, traders, refiners, and consumers during the next 10 years. Changing quality will have the most profound influence on players within the Asia-Pacific region itself. Refiners and consumers will need to make appropriate investments to give themselves greater flexibility. Traders and shippers will need to anticipate changes in trade flows both within and into the region. Nevertheless, the globalization of product markets also means that companies in other regions-especially those that depend on the ability to trade with Asia-need to understand Asia's movement toward cleaner fuels and the problems and opportunities that it entails.

Change in Asia

Our research shows that Asia is now poised to proceed up the path toward cleaner fuels that the OECD countries have blazed.

In addition, some changes in fuel quality will occur very rapidly in comparison with the Atlantic Basin experience for a number of reasons:

- The economic threshold at which people become concerned about the air they breathe and the water they drink is moving down.

- From the Atlantic Basin experience, Asia has a ready store of knowledge concerning fuel upgrading and fuel quality interactions.

- Increasingly acute pollution levels will lead to a wave of measures designed to clean up the environment. The pollution problem, already bad, threatens to worsen due to three basically unstoppable forces: population growth, economic growth, and urbanization. Countries will have to act aggressively if they hope to avoid ever more serious environmental degradation.

- Asia is undergoing a subtle transformation in which environmental issues, with urban pollution (and therefore fuel quality) high on the agenda, are increasingly politicized, creating uncertainty about the speed and destination of the development of fuel quality regulation. In the long run, we envision the accountability of governments growing and the desire to respond to the real and perceived problems of important segments of the population driving government action. Changing fuel specifications are one result of this process. In some cases, the public is already clamoring for relief from pollution, and even when it is not, politicization may still foment rapid change of fuel specifications because politicians may actively campaign on the issue. Clean fuels initiatives are political winners.

- Pollution control is increasingly a status symbol.

Deregulation

The deregulation of oil refining, retail, trade, and prices is the single most important development in

Asia's downstream sector today because it has the potential to create markets, with a number of important consequences: the development of spot crude markets, pressure to downsize, and the rise of risk.

This deregulation will benefit the lean refiners that already profit or lose by the vagaries of the market price, but deregulation will be slow.

We estimate the absolute amount of product sold under fixed prices in the year 2000 will be roughly equivalent to the current level, although the quantity sold at free prices will grow substantially.

Specifications in Asia are set to change rapidly. Just as common will be changes to the timetables of existing plans.

Countries will miss targets, and some governments will back down from aggressive plans, but this flexibility can also work both ways. In other words, governments may also accelerate targets.

Gasoline specifications

In the case of gasoline, the Asian market is in relative balance.

Because of the structure of demand and supply, we believe that the market will chronically tend to oversupply in quantitative terms.

As for the quality of gasoline, Asia now exhibits great diversity in quality from country to country. Our analysis suggests that these standards will not converge as some countries "catch up." Rather, further splintering of the market is likely as leading-edge countries push their specifications even further.

The most severe threat from the burning of gasoline in Asia remains the lead problem. Fortunately, most barrels consumed in Asia are already unleaded-71% in 1996 by our calculation.

We estimate that the demand for leaded fuels will not grow, despite the rapid growth of markets such as India and Indonesia. Rather, all incremental Asian gasoline demand growth will be for unleaded. Refiners need to be able to boost octane without resorting to lead octane enhancers.

In addition to lead, governments are likely to target lesser-known gasoline specifications:

- While it is possible that regulations will restrict the overall aromatics content of gasoline, attention will focus initially on the aromatic currently considered most dangerous: benzene. Expect governments to adopt benzene restrictions in conjunction with unleaded regulations.

- Within 10 years, we would be surprised if the majority of countries did not have minimum oxygenate specifications-usually calling for methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE).

- Most countries are not thinking yet of changes to the Reid vapor pressure (Rvp) specification, but as ozone problems increase in Asian cities, expect matters involving Rvp and volatile organic compounds (VOC) to move onto regulators' radar screens.

- Removal of sulfur from gasoline offers a relatively cheap way to clean up sulfur emissions and improves the performance of catalytic converters.

One of the principal forces revolutionizing the Atlantic Basin oil market during the past decade has been the "commoditization" of oil, which is leading to the integration of energy forms into a single market. Commoditization is not a one-way phenomenon, however. Oil products can also be de-commoditized if a market splinters.

The Asian gasoline market, already somewhat fragmented, will become more so as regulations change in an uncoordinated way.

Diesel

Viewed by governments as the engine of growth-and often subsidized for that reason-diesel fuel represents the single largest portion of oil demand in most Asian countries today.

With supply increasingly lagging demand, Asia's overall diesel deficit has risen sharply to 400,000 b/d since 1990, with the bulk supplied by the Middle East.

Without a doubt, most of the change in diesel quality in Asia will revolve around the sulfur content. In virtually every country, the sulfur maximum allowed in diesel fuel will decrease.

Our detailed country-by-country estimate concludes that the sulfur content of the weighted average barrel of diesel will fall from the present 0.34 wt % sulfur to about 0.2 wt %. This change may not sound radical at first, but consider that this decrease applies to every single barrel consumed in the region.

Companies doing business in Asia can glean insight from the experience of the Atlantic Basin, but in the end the Pacific path will be like no other. In Asia, every country will have its own plan, subject to a unique set of forces. The result of this multi-polarity is that companies' needs for accurate information and sound judgment about the various changes will increase. Constant monitoring and reevaluation will be necessary.

At present, the region's diesel sulfur content is relatively high. Importantly, at present there is virtually no demand for diesel with a sulfur content of 0.05 wt % or lower.

In just 5 years' time, the situation will look very different. The 0.05 wt % or lower portion of demand is set to explode, while our projections see demand for high-sulfur material stagnating and then atrophying over time.

Moreover, the new standard-setting in Asia may actually speed up change in countries where there are no targets or where we remain skeptical about the ability to meet set targets.

In addition to sulfur, expect two other diesel properties to be involved in fuel upgrading:

- Cetane. The major changes in diesel fuel quality will not involve cetane directly. Rather, like octane, refiners will need to develop solutions to other problems that will not cause the cetane of the fuel produced to deteriorate.

- Density. Diesel fuel density currently is not very high on the list of priorities for most fuel regulators in Asia, but its inextricable link to suspended particulate matter (SPM) guarantees that governments cannot ignore it for long. SPM is the number one pollution problem afflicting Asian countries today. Despite the lack of current proposals, we believe that a new set of regulations addressing density will arise to add to the gains resulting from desulfurization.

Fuel oil

Of all the petroleum products, residual fuel oil has the most complicated market.

The volatility of both demand and supply for fuel oil during the past 30 years has substantially exceeded that of the other oil derivatives, and market imperfections and exogenous factors have had a demonstrable effect.

Asia as a whole exhibits a large deficit of fuel oil: in 1996, the region's call on fuel oil from other parts of the world was roughly 400,000 b/d. Another important facet of the market is that trade flows of fuel oil are larger than national balances warrant due to a robust quality-based trade.

A detailed review of the four submarkets constituting the fuel oil market-bunkers, power generation, industry, and internal refinery use-paint a picture in Asia not of decline but of stability and very moderate growth during the next 5-10 years.

The balances we generate show that the sluggish growth of fuel oil demand (compared with other fuels) and substantial additions to primary refining will help reduce the region's fuel oil deficit. For the refiners, this should translate to a weakening of the fuel oil price, an improvement in the upgrading margin, and the subsequent encouragement of the construction of cracking units to remedy the situation.

The important quality parameter for fuel oil is sulfur. Resid burning is a significant contributor to acid deposition in many areas, and governments are increasingly worried about its potential effects.

At present, the total fuel oil market in Asia mixes significant quantities of all grades of fuel oil. However, the bunker market, which is all high-sulfur, accounts for a large percentage of the sour fuel oil passing through the Asian fuel oil complex. The surprising fact is that much of the Asian market already uses low-sulfur fuel oil.

In fact, our estimates suggest that only a small portion of inland sales is at the 3.0 wt %+ sulfur level generally traded in Singapore.

During the next 5-10 years, the Asian market should show some shift toward a lower sulfur content but not the kind of dramatic shift that looms in the diesel market. The difficulties will come on the supply side.

Are Asian refiners ready?

The tremendous oil reserves of the Middle East are the obvious sources of crude oil for Asia's growing demand.

As Asia's preference for clean light products and even clean heavy products increases in the next several years, however, this obvious source of crude will become increasingly inappropriate to meet Asia 's needs. The inescapable fact is that much of the Middle East's crude output is and will remain heavy, and an even larger portion is and will remain sour.

As Asian oil demand grows, Asian refiners will have to look further and further afield to find and purchase sweet crude oil. The most obvious source of light, sweet crude for import to Asia will continue to be Africa, especially West Africa.

Africa's export surplus should grow by at least 1 million b/d in the next 10 years. Most of this sweet surplus will be pulled to Asia but at a price that reflects competition with light, sweet crude consumers in the Atlantic Basin.

Compared with the cost of building new refineries, upgrading projects are cheap and rather easy. Nevertheless, they add up, and the aggregate cost of refinery secondary and upgrading units (including crackers) in Asia during the next decade will almost certainly be higher than the cost of the new primary distillation capacity.

For gasoline, as more and more barrels become unleaded, Asian refiners will have to find ways to replace the octane value formerly supplied by lead. However, given the adequacy of reforming capacity, we do not expect that further switching to unleaded (which is limited, anyway) will necessitate much additional investment.

The real trick for refiners will be in anticipating the next set of rules, which is likely to revolve around aromatics, ozone precursors, sulfur, and VOCs. Compliance with these specifications will necessitate solutions beyond tweaking existing units.

For the next 3-5 years, the action in the Pacific diesel market will center on sulfur removal, and, to a lesser extent, cetane levels. Only later will issues such as density and aromatics content necessitate investments. As a whole, the Asian refining system is currently able to meet the regional diesel quality demands, even though the "balancing barrels" that the region imports tend to be of fairly low quality.

Unfortunately, this environmental self-sufficiency is fading. Our research suggests that the dramatic transformation in diesel quality will lead to a situation in which several key countries will be unable to meet their own demand. More hydroprocessing capacity than is currently planned will need to be constructed.

Residual fuel oil is by far the most difficult to clean up, both technically and economically. The reality is that resid desulfurization is extremely expensive-perhaps as much as four times the cost of hydrotreating middle distillates. Thus, the practice of removing sulfur from fuel oil in order to capture the premium commanded by low-sulfur resid is extremely rare. Except in Japan, there are almost no resid desulfurizers in the refining system, and supply into the low-sulfur market comes from refining sweet crude oil.

Our analysis suggests that the low-sulfur market is balanced tenuously at present, and we believe it could experience a significant tightening in the next few years due to changes in the regional crude slate and the diminishing availability of Asian low-sulfur exports, especially low-sulfur waxy resid.

Our view contends that Asian consumers will wind up paying premium prices for low-sulfur fuel oil, not because its demand will expand, but because its supply will wane.

Clean fuels consequences, strategies

Our research concludes that producers who fail to understand the new dynamics driving changes in product quality and who do not make appropriate decisions risk being caught selling low-quality products into shrinking markets.

While a strategy focusing on low-quality, low-cost sales may be profitable if low-quality supply evaporates faster than expected, we believe that more often than not, quality premiums will arise, and unprepared refiners will not be able to capture any of these.

The consequences of this "Clean Revolution" are far-reaching and long-lasting for all players involved in the buying, trading, selling, and storage of oil products. The following strategies can help companies emerge as victors rather than as victims:

- Understand the process. The cleaning up of oil products is an open-ended process rather than a fixed goal. Having a sound understanding of the reasons for the trend to cleaner fuels and accepting this as an economic reality will reduce frustration and engender corporate structures and attitudes that are more likely to succeed in the new and changing environment. In other words, cleaner fuels are inevitable; companies that look for opportunities to be found in this time of change will outperform those that have to be dragged kicking and screaming into the 21st century.

- Influence the process. While the drivers of the clean revolution are, for the most part, beyond the control of oil companies, companies can benefit by participating in the unfolding of the trend and influencing the shape and texture of the eventual outcome. In the democracies of the West, all parties involved in creating standards (oil firms, environmental groups, citizens' associations, and government agencies) use sophisticated lobbying and public relations techniques in seeking to alter the outcome of the battle over regulations. Asian companies will need to develop new sets of skills if they hope to affect the regulatory process in a way that adds value to a company's reputation, business environment, and bottom line.

- Examine the possibility of becoming a "clean fuel" company. Some companies may be able to use market turmoil to remake themselves or turn previous disadvantages to profitable use. We believe that the move to higher quality will provide a boon to Asia's sophisticated refiners-particularly the Japanese-that have performed so poorly in recent years. Specification changes create export opportunities; they can be used as a barrier to imports under certain circumstances; and they can turn price-takers into price-makers. To achieve these benefits, selected oil companies in Asia may want to actually embrace-or even promote-tightening standards.

- Expect inter-company gamesmanship. If our view of the future of oil product regulation proves correct, sellers and buyers will face one fundamental choice concerning investment: do it now or do it later. Eventually, all market participants will have to make the adjustments necessary. Each company will need to gauge its position in the queue of companies undertaking investments and make decisions accordingly.

- Accept the possibility of a poor rate of return. Even making appropriate changes will not guarantee the profitability of investments for all-or even many-companies. In fact, in the Atlantic Basin today, companies almost universally view the costs associated with environmental regulation compliance as nonrecoverable. Good decisions have substantial impacts, but investments for upgrading fuels generally offer a subpar rate of return to the companies, and some actually result in a loss.

- Anticipate mis-timing and windows of opportunity. Market discontinuities near the times of introduction of new specifications are likely to open "windows of opportunity" that will benefit refiners and consumers who are ahead of the curve in understanding and preparing for specification changes. Some of these anomalies may persist due to financial, political, or technical constraints.

- Understand the ramifications of a sulfur squeeze: Shortages of low-sulfur products are inevitable, in our view, during the next 5 years. Refiners will first react by sweetening their crude slate, affecting all regional refiners. The next strategy involves importation of low-sulfur products available on the international market, first locally, then from outside the region. Finally, refiners will construct desulfurization capacity to ensure a more permanent solution to sulfur squeezes, at least in the diesel market.

- Refiners in the Middle East may have real problems meeting specification changes in Asia. ESAI's refining database shows that Middle Eastern refiners will substantively expand distillation and cracking capacity during the next 3 or 4 years, generating imports that will ostensibly move to Asia. Yet, the bulk of the projects at present do not focus on creating higher-quality products, despite the sour crude feed for the refineries.

- Focus on flexibility. To counter rising uncertainty and intensified risk, both consumers and producers need to work to develop corporate structures and projects that emphasize flexibility and create choices for companies under a host of contingencies.

- Develop blending capability. The move toward micromarkets in Asia due to uncoordinated standards should enhance the value of blending operations for both crude and products. Blending operations and/or simple facilities that are able to desulfurize or reform or otherwise change the quality of oil products will gain from grade differentials exacerbated by increasingly manipulated markets.

- Watch out for de-commoditization: Consumers in countries with tightening specifications are vulnerable to difficulties emanating from the supply side. As deregulation slowly creates markets, rising price risk will push consumers to look for tools to manage their risk. Consumers must be careful to choose instruments that are: appropriate to the changing fuel specification environment, robust enough to maintain adequate liquidity, and based on the least manipulated and most fair pricing scheme.

Copyright 1997 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.