Commission ushers in new era in Mexican gas industry

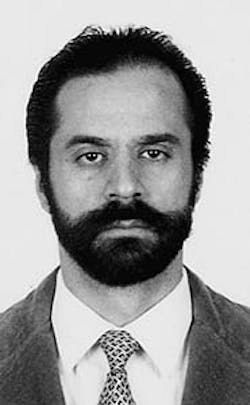

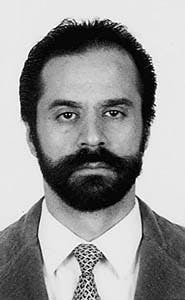

Raúl MonteforteTransportation and distribution of natural gas in México are undergoing fundamental changes as a result of the 1995 passage by the Congress of México of the law that created the Energy Regulatory Commission (Comisión Reguladora de Energía-CRE).

Energy Regulatory Commission of México

México City

The commission has five commissioners, including a chairman, appointed by the president of México.

The law mandates that the commission must achieve a competitive, efficient, safe, and sustainable gas industry, allowing the country to make the difficult energy transition to open gas and electricity markets relying on cleaner fuels.

Situation before CRE

Until 1995, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) controlled the gas industry in the country. Its grip included all segments of the industry: upstream, midstream, and downstream (Fig. 1) [73,437 bytes].Exploration and production of petroleum and gas, especially, as well as the firsthand sales of both products, were exclusive prerogatives of the Mexican government through the 60-year-old Pemex. Official statements have made it clear that this status in exploration and production is likely to stay, and there are understandable and compeling political reasons for this.

Government control has consisted of gas processing, gas imports, and gas transmission through the national pipeline network. Furthermore, Pemex' monopoly has included system extensions, branches, and connections even if the users built them.

Additionally, Pemex, as much as other government utilities, has been involved in gas distribution within population centers. The most important users have been state petrochemical companies and the national electric utility.

Small clusters of private distribution companies have survived for decades in this environment, particularly in northern México, providing distribution services in some cities. But these companies have endured many problems related to, on the one hand, investment, technical development, and growth and, on the other, contracts, payments, and supply relationships with Pemex.

By 1995, the gas industry in México appeared hopeless. Investment was so lacking that infrastructure lagged the needs of the economy.

At the same time, services were restricted and unreliable. As a result, inadequate fuel mixes prevailed, and there were frequent reliability problems and widespread inefficiencies. Clearly, restructuring of the industry was needed.

In that year, the Mexican government launched gas reform based on defined energy policies and legal changes.

Strategic considerations and a clear diagnosis of energy priorities provided the necessary foundation to this process of reform. The Ministry of Energy (Secretaría de Energía) conceived the reform and has since continuously supported its development. Fig. 2 [63,948 bytes] shows how México's natural-gas industry is envisioned under the new regulatory regime.

Gas reform aimed at solving identified problems and bottlenecks in this industry and at promoting gas consumption and related investments. Topping the list of priorities was the achievement of vital energy goals, such as fuel substitution and use of cleaner fuels.

The legal and institutional reforms focused on creation of a solid platform for private investment in gas transmission, distribution, and storage. This comprehensive reform required a new regulating authority with power and autonomy for regulating existing public and private monopolies, as well as the new participants in a wholly transformed market.

Regulatory framework

These changes have altered the long-term vision of the gas industry in an unprecedented way. Now, activities reserved to Pemex are concentrated only in supply. The midstream and downstream segments of the industry are completely open to the private sector.The national pipeline network, while remaining under the control and ownership of Pemex, is subject to new regulations. These include mandatory open access, general terms and conditions of service, and regulated rates. Moreover, an increasing number of privately owned transmission pipelines will create networks across the national land.

Distribution will be performed totally by private companies entitled to make their own supply arrangements and undertake their own commercial activities.

Based on the Law of the Energy Regulatory Commission, CRE leads in development of the new gas industry.

CRE decides by majority vote, and all resolutions are public. Public consultation has been and will remain an important tool for CRE to rule on strategic matters. CRE maintains an Internet site (www.cre.gob.mx) which contains, among other information, reasons for a given decision, and the texts of orders and permits, along with a listing of CRE staff and functions.

The commission has created a complete set of legal instruments to accomplish its mission:

- The Natural Gas Regulation embodies the main group of regulations dealing with the nature of the regulated services, as well as the permit regime for gas-related activities.

- The directives (or orders) on prices, accounting, and geographic zones, and the technical standards for the gas industry are also powerful tools regulation.

- The commission requires technical standards that follow internationally accepted practices to ensure high technical capability, safety, and reliability in all segments of the industry. In this way, México should be able to make the industry's performance conform closely to the generally accepted standards of those in nations with mature gas markets.

- Finally, CRE regulates the industry through the permits themselves, which contain a number of specific obligations, and specific orders, as each case requires.

Furthermore, the CRE started a process of competitive bidding for geographic zones leading to the issuance of distribution permits to the winners. Fig. 3 [79,927 bytes] presents the geographic zones and bid status for each; Table 1 [18,615 bytes] presents a summary of bids to date.

Regulations are being applied to Pemex' monopoly in order to grant the company the permits for gas transmission and first-hand sales. The permit regime also targets private transportation as a public service and transportation for self use, that is, transportation by, for example, private firms which own pipelines to serve only their own needs.

The CRE has many other tools to support development of the domestic gas market. These include enforcement of the regulations, and supervision of such crucial aspects as safety, efficiency, orderly transition to the new regime, and fairness in the provision of services.

The commission also has the power to inspect facilities and to arbitrate in controversies.

Finally, The commission plays a decisive role through price regulations, as much for firsthand sales as for transportation and distribution rates. In both cases, CRE tries to instill international price references and concepts that buttress competitiveness and incentive-based regulations.

Market development

Competitive bidding for geographic zones is an important and novel process in México.The CRE has completed international competitive bids in seven Mexican cities, most recently Monterrey. The last major one in progress is for México City, consisting of the two largest LDC areas in México. Further bids will be published this year and next for geographic areas in the north and in the center of México, including some of the main population centers and industrial sites. Eventually, a bid will be issued for the southern city of Merida, consequent to the coming on line in 2004 of the Mayakan pipeline across the Yucatan peninsula.

Bid winners tend to be powerful consortia in which there often is, or will be, direct and indirect participation by Mexican companies in the different stages of the distribution systems.

The effect on domestic economic activity and jobs will be strong and positive. Some special features of these bidding processes deserve further analysis.

Fundamentally, it is a competitive mechanism: The best proposal meeting the highest possible standards at the lowest prices (regulated income per unit) wins the bid.

However, irrespective of the bid price, circumventing the regulations (even if inadvertent), disguising information, or attempting to dodge established procedures will lead to certain disqualification.

When the Río P nuco bid took place, for example, two consortia were disqualified (Gaz de France-Buffete Industrial and Shell-BC Gas-GMD). The two subsequently appealed, with extensive media coverage, but the CRE made a complete review of the case and on Dec. 15, 1997, upheld the decision to disqualify.

The CRE evaluates the bids based on technical and economic criteria clearly stated in the bid documents. These criteria are based on sound engineering considerations, the safety of the proposed systems, and the relationship between system design, costs, volumes, minimum coverage, customer base, and investment viability, among others.

The process culminates with the granting of a permit for 30 years and the concession of exclusivity inside the geographic area for 12 years.

Gas transmission also is subject to the permit regime.

The CRE evaluates the technical and economic parameters that rule the pipeline industry to ensure safety, reliability, quality services, and competitive rates. Transportation permits are valid for 30 years, albeit there is no exclusivity, and the situation may become very competitive.

Fig. 4 [102,655 bytes] presents some probable and prospective gas-transportation projects; Table 2 [11,884 bytes] presents a list of transportation permits awarded through Feb. 1, 1998.

For example, the CRE may grant several permits for the same route, or it may grant permits for two competing routes serving the same markets. It has done so in the case of Palmillas-Toluca and Jilotepec-Toluca, where Tejas Gas will compete against NOVA-NGC. Incidentally, this form of competition has precluded any possible vertical integration with the LDC in Toluca.

The CRE can also grant permits to self-users alongside an open-access transmission pipeline. Vertical integration is generally not allowed; its presence would depend on very special and fully justified circumstances.

Finally, pipelines may not deliver gas to endusers inside franchise areas, only to other permit holders; that is, distribution companies and self-users holding permits. Hence, physical and commercial by-pass is allowed, subject only to minimum volume requirements.

The permit application must include full definition of route and capacity.

Mandatory open access and the possibility of capacity release are two significant aspects of the new transportation segment of the industry. Rates are regulated according to the principle of maximum yield per unit of gas (maximum regulated income).

Finally, the regulations require consistent standards for operations and transactions in the pipeline industry. These include capacity booking, nomination procedures, flowing-gas standards and, generally, business practices such as contracting and billing. These standards will gradually follow those currently implemented by U.S. Gas Industry Standards Board.

The case of PGPB

The transportation permit of Pemex Gas y Petroquímica B sica (PGPB) is fundamental for the new gas industry in México (Fig. 5 [71,848 bytes]).Until 1995, the PGPB monopoly provided bundled services including gas deliveries sold and transported by PGPB as a sole supplier. Balancing the system was entirely in the hands of the monopoly, and operation rules and standards were discretionary and arcane.

Contracts were often whimsical and unreliable, and rates would hide almost everything, from cross-subsidies to "indirect" costs, under a unique volumetric concept.

The new regulations require PGPB to obtain its definitive transmission permit, subject to the maximum rate regulation that exists in the country. This implies that in 1998 the national pipeline network is subject to mandatory open access and will be under obligation to transport thirdparty gas.

Services will be unbundled, and users will have to book for capacity and nominate their gas deliveries while being responsible for injection and delivery of their own gas. This entails that new, complex balancing procedures and detailed, documented operation rules be in place and included in PGPB permit.

A thorough definition of capacity must contain availability parameters and utilization factors for every combination of routes. Rate calculation will follow a methodology that considers capacity-distance charges and will be subject to the caps set forth by the pricing directive.

Most significantly, as a vital document in that permit, the General Terms and Conditions of Service (GTS) will frame the provision of services and the contracts themselves.

Simultaneously, first-hand sales will be regulated according to the principles of nondiscrimination, contract transparency, consistency, and supply reliability, which will be included in the General Terms and Conditions for the First-Hand Sales of Natural Gas.

Complying with the regulations has turned out to be a major challenge to PGPB as well as to the commission. This is due to the requirements imposed by the CRE, the rigidity and some lethargic practices at PGPB, and to some budgetary and staffing lilmits at CRE.

Nevertheless, the new framework offers the best business opportunities to PGPB for the long term, compared to the previous system, which was unreliable, burdensome, inefficient, and unprofitable for PGPB. The whole country was paying for this, including Pemex, as everyone must now recognize.

North American market

The open-access program is a major undertaking that will cover more than 11,000 km of interconnected pipeline in México. The program is gradual according to the competitive potential of the different regions and the technical capability of implementing it, particularly in terms of measuring and controlling equipment.The objective is to configure an open and seamless system integrating third-party contracts and nominations into the schedule of pipeline operations. While this is the rule in countries with developed and competitive systems, in México one big, lagging monopoly must perform this assignment.

This is a very different problem from open access and unbundling in a huge maze of advanced interstate and intrastate pipelines with well-established LDCs and long-standing users, which is the case in the U.S., for example.

Given the specific circumstances, providing effective open access could be comparatively more manageable in México due to centralization itself and to the smaller number of actors involved. However, other difficulties, including technical inadequacy and resistance from the monopoly, may arise for the same reasons.

This process also stands out because PGPB is adopting GISB standards for cross-border transactions as a result of the interaction with U.S. pipelines, while their proposed GTSs are including similar standards for domestic transactions.

This convergence perhaps says more than the standards themselves about the likely configuration of a truly North American gas market.

Transportation for selfuse is a noteworthy market phenomenon. Already, the CRE has granted 13 permits of this kind, and many more will follow (Table 3 [12,707 bytes]).

Most likely, they are private firms wanting to own pipelines as a constituent part of their business strategies to consolidate their own infrastructure, or raise their competitiveness, without being predated by an LDC or gobbled-up by the state monopoly.

Characteristically, these projects are increasingly appearing as an inseparable component of industrial parks, and/or as integrated energy projects where electricity and gas converge.

The Author

Raul Monteforte is a commissioner in México's newly formed Energy Regulatory Commission, appointed by the country's president for 1996-1998. He has been a professor and researcher at the National Autonomous University of México, a consultant to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization and to the Economic Commission for Latin America, an advisor at the Institute of Electrical Research of México, a director of projects at the National Institute of Ecology of the Mexican Ministry of the Environment, and chief of staff for the Deputy Secretary of Energy Policy and Development, Mexican Ministry of Energy.Monteforte holds a BA (1982) in social and political sciences from the Autonomous University of México, and an MS (1984) and PhD (1989) in energy and development studies, both from the University of Sussex (U.K.).

Copyright 1998 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.