CAFE program midterm evaluation should consider oil-market changes

Lucian Pugliaresi

Max Pyziur

Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc.

Washington, DC

Unforeseen changes in the oil market need consideration in the US Environmental Protection Agency's imminent review of an important element of transportation-fuel regulation. Since enactment of corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards in the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, the market has invalidated several strong assumptions on which Congress based the legislation.

Like most observers in the mid-1970s, congressional leaders believed US production of crude oil had begun an endless decline. Yet, in a remarkable achievement of technical innovation and risk-taking, production surged from 5 million b/d in 2008 to more than 9.5 million b/d in mid-2015.

When they created the CAFE program, lawmakers also expected gasoline consumption growth to continue unless damped by regulation, combining with the production slide to make rising US dependence on foreign oil dangerously inevitable. Those expectations haven't come true, either. US demand for blended gasoline supplies has remained relatively flat since 2006. Consumption of gasoline in fact has declined as growing volumes of ethanol enter the gasoline pool, now at about 10% of the total. And with crude production rising and demand for the dominant US oil product no longer growing, net imports of crude and products-a crucial concern of the 1975 energy bill-have plummeted. Having exceeded 12 million b/d in 2006, net imports in the early months of 2016 averaged about 4 million b/d.

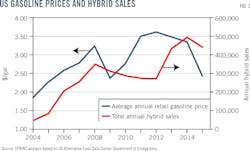

These departures from past expectations are products of a new era of abundance that Congress could not foresee when it introduced CAFE standards. The swing away from scarcity has lowered oil prices dramatically, further challenging assumptions out of which CAFE standards emerged (Fig. 1).

The program

CAFE standards were designed to increase fuel efficiency of new vehicles, thereby limiting fuel consumption. In 1975, after elevation of fuel prices by the 1973 Arab oil embargo, Congress was unwilling to reduce gasoline consumption through taxation. Instead, it passed a mandate requiring manufacturers and marketers to assemble vehicles with minimum fuel-efficiency performance.

The CAFE program has continued to raise performance requirements. Today, the standards require complex assessments of the performance of individual vehicles and of a manufacturer's entire fleet in any given model year (MY). Utilizing a challenging accounting method, the standard seeks to achieve improvements in fuel economy and reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; however, the summary metric is expressed in miles per gallon. While implementation has been controversial and uneven over time, overall there has been little challenge to the view that the CAFE standards have caused fuel economy to approximately double between the 1970s and the mid-1980s.

An emerging concern about toughening CAFE standards is diminishing returns from higher fuel-mileage requirements. The Energy Information Administration has shown that modest improvements in fuel economy in less-efficient vehicles produce incrementally greater value than large improvements in more-efficient vehicles. In Fig. 2a, the top line in the chart shows that even when the gasoline price is $3.50/gal, consumers can expect the same annual savings of $700 in fuel costs from an improvement in fuel economy by lifting the vehicle performance from 12 mpg to 15 mpg as from 30 mpg to 60 mpg. When the gasoline price is $2.25/gal, closer to current trends, as shown in the bottom line in Fig. 2a, these savings are only $450.

Similarly, the relationship in the improvements in the reduction of GHGs follows a pattern of diminishing returns the same as that of fuel efficiency (Fig. 2b). One gallon of gasoline generates 8,887 g of CO2 emissions. At 10 mpg, 888.7 g of CO2 is generated. That is cut in half by a 10 mpg increase in fuel efficiency. To achieve the next halving of GHG-generation (reduction to 222.2 g/gal of gasoline consumption), fuel efficiency has to double to 40 mpg from 20 mpg.

Midterm evaluation

In mid-2012, the EPA and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued the final rule for GHG emissions and fuel economy standards for MYs 2017-25 for passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium-duty passenger vehicles. Each agency has unique responsibilities for establishing mileage performance standards.

As part of the rulemaking establishing the MYs 2017-25 light-duty vehicle GHG standards, EPA made a regulatory commitment to conduct a midterm evaluation (MTE) of longer-term standards for MY 2022-25. EPA will coordinate with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the California Air Resources Board in conducting the MTE.

As required by law, NHTSA developed two phases of standards in the rulemaking. The first phase, for MYs 2017-21, includes final standards projected to require, on an average industry fleet-wide basis, a range of 40.3-41.0 mpg in MY 2021. The second phase of the CAFE program, for MYs 2022-25, includes standards that are not final due to the statutory requirement that NHTSA set average fuel economy standards not more than 5 MYs at a time.

Thus, the second-phase standards represented NHTSA's current best estimate, based on the information available to the agency when the final rule was adopted of what levels of stringency might be maximum feasible in those MYs. NHTSA projects that those standards could require, on an average industry fleet-wide basis, a range of 48.7-49.7 mpg in MY 2025. At the same time, EPA is establishing standards projected to require, on an average industry fleet-wide basis in MY 2025, fuel economy of 54.5 mpg to achieve reductions in GHG emissions.

Auto manufacturers are required to meet a specific and more stringent standard on average in each MY from 2017 through 2025. Because the standards are based on the vehicle's footprint, the burden of compliance is distributed across all vehicle footprints and across all manufacturers. Manufacturers are not compelled to build vehicles of any particular size or type (nor do the rules create an incentive to do so), and each manufacturer will have its own fleet-wide standard that reflects the light duty vehicles it chooses to produce.

The two agencies estimate the MY 2017-25 national program will save 4 billion bbl of oil and reduce GHG emissions by the equivalent of 2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent over the lifetimes of those light-duty vehicles produced in MYs 2017-25. The agencies project that fuel savings will far outweigh higher vehicle costs and that the net benefits to society of the MY 2017-25 national program will be in the range of $326-451 billion (7% and 3% discount rates, respectively) over the lifetimes of light-duty vehicles produced in those years.

The agencies estimate that technologies used to meet the standards will add, on average, about $1,800 to the cost of a new light-duty vehicle in MY 2025 and that consumers who drive their MY 2025 vehicle for its entire lifetime will save, on average, $5,700-$7,400 (7 and 3% discount rates, respectively) in fuel costs, for a net lifetime savings of $3,400-5,000. This estimate assumes gasoline prices of $3.87/gal in 2025 with small increases most years throughout the vehicle's lifetime.

The National Resource Council's (NRC) Board on Energy and Environmental Systems independently assessed the new miles-per-gallon standards. On balance, the NRC commended the agencies for offering a standard-setting approach that allowed manufacturers more flexibility. But it found the rapid pace of required product development raised concerns about the potential for stranded capital. While the report reviews the entire range of strategies to meet the new standards, it largely did not address the issue of a substantially lower long-term price for transportation fuels.

One technology that mitigates GHGs and raises fuel efficiency that has shown strong acceptance is the hybrid-electric vehicle (HEV). Popular HEVs include the Toyota Prius and Ford Fusion. However, HEV sales closely track that of the price of gasoline: Rising fuel prices align with increasing HEV sales, and vice-versa (Fig. 3).

EPA's decision

Through the MTE, EPA will decide whether the standards for MYs 2022-25, established in 2012, remain appropriate given the latest available data and information. EPA's decision can go one of three ways: The standards remain appropriate, the standards should be less stringent, or the standards should be more stringent. EPA will examine a wide range of factors, such as developments in powertrain technology, vehicle electrification, light-weighting and vehicle safety impacts, the penetration of fuel efficient technologies in the marketplace, consumer acceptance of fuel-efficient technologies, trends in fuel prices and the vehicle fleet, employment impacts, and many others.

As a result, the upcoming MTE should directly address challenges, among other concerns, from the new pricing environment. Among important questions are the following:

• How are consumer preferences for vehicle size and performance likely to shift in an environment of low gasoline and diesel prices?

• Given that justification for the new CAFE standards relies substantially on a calculation of economic benefits to consumers from fuel savings, what is a likely range of the reduction in economic benefits under a low-price scenario?

• Is this new price environment likely to raise the amount of stranded capital as auto manufacturers adjust to address the shift in consumer preferences in a lower fuel-price environment?

• What are the implications to the growth and stability of the auto industry in the new price environment?

• How might a wider range of compliance strategies, including some modest adjustments to the miles-per-gallon and footprint requirements, substantially lower the compliance cost of the new standards?

• What future policies provide the best balance of cost, risk, and environmental performance given the new fuel-pricing environment?

Adapted from an EPRINC study published in February 2016.

The authors

Lucian (Lou) Pugliaresi is president of the Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. (EPRINC), a not-for-profit organization formed in 1944 that studies energy economics and policy issues with special emphasis on oil, natural gas, and petroleum product markets. Pugliaresi has served in a wide range of government posts, including the National Security Council at the White House (Reagan administration); Departments of State, Energy, and Interior; and Environmental Protection Agency. He graduated from the University of California at Berkeley with an AB in economics (1970).

Max Pyziur is EPRINC's senior advisor-downstream projects. Previously he has held senior analytical roles at PIRA Energy and CPM Group, both commodities market consultancies, and at financial service organizations such as Victory Capital and Banc of America Securities. He has an MBA from Washington University in St. Louis and a BA from St. Louis University.