Why the oil companies make bad villains

Jude Clemente, San Diego State University, San Diego, Calif.

Whether it was the proposed "windfall" profits tax in 2008, the price drop that "diverted" renewable energy investments in 2009, or the "greed" that caused the BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010, it seems the US oil industry gets blamed for most everything these days. In the wake of the Horizon incident, renewed calls for "forcing Big Oil to pay its fair share" are echoing more loudly than usual.

For example, Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, wants oil profits to be "given back" to society via multibillion-dollar taxes because they result from "good luck," and, according to him, companies "didn't do anything" to deserve them.

Unfortunately, the only relevant exposure the typical American gets to the oil industry is at the local fill-up station, where each day producers supply the nine million barrels of gasoline required to fuel the US fleet of 265 million vehicles. And a double-digit increase in gasoline prices in the past year has oil companies once again on the defensive.

The anti-oil lobby has been markedly more vitriolic since the crude price spike in the summer of 2008:

- "The unbearable arrogance of oil…..[is] a spectacular testament to the iron grip that Big Oil has on American politics," Carl Pope, then-executive director of Sierra Club, July 17, 2008

- "Credible institutions like…..the US Congress need to stop doing business with un-credible institutions like the American Petroleum Institute…..It's part of this huge campaign of Big Oil to sap tax dollars," Phil Radford, executive director of Greenpeace, Dec. 4, 2009

- "Giving Big Oil more access to our nation's waters will only lead to more pollution, more lost jobs, and more damage to our economy," Frank Lautenberg, US Senator (D-NJ), May 27, 2010

Nevertheless, oil's leading role in the US energy portfolio is virtually guaranteed to continue. Under the International Energy Agency's (2010) optimistic 450 Scenario, which assumes "collective policy action is taken to limit the long-term concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to 450 parts per million of CO2-equivalent," oil will still constitute 30% of our total primary energy demand in 2030.

Today's complex interaction between energy security and climate change challenges likely marks a historic turning point for our nation's oil policy. Because a single cartel, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, controls more than 80% of the world's proven oil reserves, the US clearly needs policies that enhance, not impede, the domestic suppliers of this irreplaceable liquid fuel.

The following analysis seeks to contribute by providing a better understanding of: 1) the oil industry's ownership, 2) the industry's profit margins, and 3) the beneficiaries of the industry's profits. Indeed, misconceptions abound.

Who owns the US oil industry?

"This study disproves the popular misconception that 'Big Oil' is owned by a small group of industry insiders. In reality, across the oil and natural gas industry only 1.5% of shares of public companies are owned by company executives. The data show that ownership of industry shares is broadly middle class, with the majority of industry shares held by institutional investors, often on behalf of millions of Americans through mutual funds, pension funds and individual retirement accounts," – Robert Shapiro, co-author of The Distribution of Ownership of US Oil and Natural Gas Companies, Sept. 19, 2007

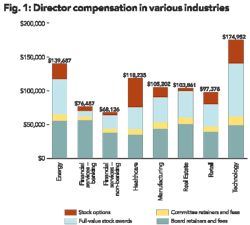

Contrary to popular belief, the US oil industry is owned by middle-class Americans, not wealthy corporate elites. That is because most of company shares are held by the tens of millions of everyday citizens that have mutual funds, pension funds, and IRAs. From teachers' retirement plans to "Mom and Pop" investors, the ownership of the oil industry is dispersed among a wide range of institutions and individuals (see Figure 1). Shapiro and Pham (2007) conclude:

- Nearly 43% of oil company shares are owned by mutual funds and asset management companies that retain mutual funds. Mutual funds manage accounts for 55 million US households (half of the national total), with a median annual income of $68,700.

- Some 27% of shares are owned by other institutional investors, namely pension funds. In 2004, more than 2,600 pension funds run by federal, state, and local governments held $64 billion in shares of oil companies. This money is the main financial security blanket for many current or retired military personnel, teachers, police officers, and firefighters.

- About 14% of shares are held in IRA and other personal retirement accounts. The roughly 45 million households that own these plans have an average account value of just more than $22,000.

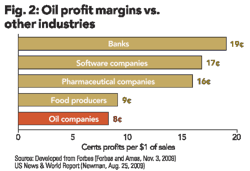

- An oil company's profits (earnings) are its net income and denote if the firm is profitable after taxes. They do not, however, illustrate how effectively resources are being deployed. Thus, solely judging the wealth of a company by its earnings can make larger, highly capital intensive companies, like those that thrive in the oil industry, appear much more "rich" than they actually are. Profit margins, or earnings per $1 of sales (measured as net income divided by net sales), are a useful tool to compare financial performance among companies and industries of all sizes. Pride et al. (2009) report "the average return on all sales for all business firms is between 4% and 5%." Although oil companies normally operate above this percentage, earning an average of $0.073 on every $1 of sales from 2005 to 2009, they fall below the S&P 500 average of 8.5%.

- As demonstrated in Figure 2, profit margins for oil companies are generally far less than those of other important industries. Pfizer, for instance, the world's largest pharmaceutical firm, has enjoyed huge profit margins of $0.292 in recent years. The lower margins for oil companies signify a greater chance that a decline in sales would erode profits and result in a net loss. Long lead times, massive capital requirements, and returns realized only decades later have oil companies constantly operating in the face of major investment risk.

Who benefits from the oil industry's profits?

Oil companies use their profits for two purposes: 1) to pay dividends to shareholders and 2) to fund the large capital investments required to find, produce, process, and transport products to consumers. Firms also utilize available cash to pay down debt and buy back shares of stock, thereby enhancing the company's overall value for investors.

Indeed, the anti-oil campaign misuses the necessity for oil companies to make heavy investments in places few Americans ever get to see, such as Alaska's North Slope, the deepwater of the Gulf of Mexico, and the North Sea. The entire country gains, however, when firms produce from these difficult areas because oil meets nearly 40% of our total primary energy demand, and more than 70% of the industry's ownership is in the form of mutual funds, pension funds, and IRAs – the bulk of which are held by the middle class.

According to the US Census Bureau, $75 billion of the $198 billion in earnings the major oil companies made in 2008 was returned to shareholders through dividends. This 38% dividend payout ratio is above the average for the S&P 500, which has dropped from about 50% in the 1990s to 31% today. The higher payback rate of oil companies is remarkable considering the substantial funds required to find, produce, process, and transport oil.

After a record high of 230 in 2008, IHS CERA reports the upstream capital costs index, benchmarked to 100 in the year 2000, reached 207 in 2010. Rising demand for oil is creating widespread shortages in labor, equipment, and raw materials within the global industry.

Simply put, oil companies are good investments. Three of the top 20 firms in the Fortune 500 are in the oil business – ExxonMobil (2nd), Chevron (3rd), and ConocoPhillips (6th). And from 1999 to 2009, only one of the 20, McKesson (11.6%), had a higher annual "total return to investors" percentage than these three majors; ExxonMobil (7.7%), Chevron (9.4%), and ConocoPhillips (10.9%).

By comparison, Berkshire Hathaway, Wal-Mart, and IBM had return rates of 5.9%, 1.5%, and -3% respectively. In fact, 8 of the 20 had negative return rates, and a number of them, including American International Group, JP Morgan Chase, and General Electric needed huge taxpayer-funded bailouts. The oil and gas sector, on the other hand, is contributing over $1 trillion to the national economy:

- PricewaterhouseCoopers reports the oil industry supports more than six million jobs, accounting for 3.5% of the total employment in the country. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates employment in oil and gas extraction carries a mean annual salary of $72,000, versus $42,000 for real estate and $63,000 for those in the computer and mathematics industry.

- The oil and gas sector has a 48% tax rate, compared to 28% for the rest of the S&P 500. In 2008, ExxonMobil paid two and a half times more in total taxes ($116 billion) than it made in earnings ($45 billion). That year, ExxonMobil dished out a staggering average of $318 million in taxes every day. Royalties, rental payments, and other fees on oil development pay for critical societal infrastructure, such as schools, hospitals, and roads.

Conclusion

As stated by John Felmy, chief economist at the American Petroleum Institute (API), those seeking to punish oil companies by seizing more of their profits are "not targeting industry executives but the hard-earned savings of working people." Oil's dominant role in the US energy economy will persist even under the best of circumstances for renewables, and unfair polices against the industry would hamper a vital revenue stream for increasingly cash-strapped federal, state, and local governments. OPEC's extending nationalistic grip on the global supply chain confirms we need policies that support domestic producers by making them as internationally competitive as possible. Profits allow firms to reinvest in the infrastructure and emerging technologies that will help us avoid the fierce competition for energy in the years ahead. The US Energy Information Administration predicts domestic oil (all liquids) production could expand by nearly 70% by 2030.

Further, API notes oil companies are leading the race toward low-carbon energy technologies: "US oil…..companies are pioneers in developing alternatives…..from geothermal to wind, from solar to biofuels, from hydrogen power to the lithium ion battery for next-generation cars."

For example, ExxonMobil plans to invest over $600 million in algae-based biofuels, Chevron is the world's largest producer of geothermal energy, and ConocoPhillips is offering cash awards for graduate research in sustainable energy systems.

From 2000 to 2008, T2 & Associates and CEE found the oil and gas sector was responsible for over $58 billion of the $133 billion invested in all CO2 mitigation in the US, compared to 52% for other private industries and 14% for the federal government. The Center for American Progress concludes these low-carbon investments by oil companies have created over one million "green jobs."

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com