Joint venturing in the oil and gas industry

Dale Nijoka,Ernst & Young, Houston

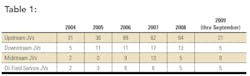

The economic downturn has resulted in the number of joint ventures (JVs) announced to the markets dropping by approximately 50% in the first half of 2009 from the levels seen during 2006-2008.

This is hardly surprising and mirrors the reductions in new projects being initiated and announced in the same period due to economic uncertainty and lower oil and gas prices. Higher cost production, such as tar and shale sands, has slowed significantly in the downturn, and this has further impacted the number of new JVs being entered into.

The focus for most oil and gas companies in this period has been on cost management and delivering on existing projects, as opposed to initiating new projects. However, with talk of a number of "green shoots" in the economic landscape and a recovery in the price of oil, Ernst & Young is starting to see early signs of an increase in the number of new exploration and production projects.

With capital markets being both constrained and restrained, there is a convergence of factors that indicate an increase in the number of JVs being announced.

Why consider a JV?

JVs are a well-established feature of the oil and gas industry. They are typically less risky and are easier to unbundle than full organization mergers. With the scale of organizations within the oil and gas industry, antitrust concerns, and the importance of national energy security, JVs are a useful way of gaining the benefits of collaboration without the economic and political risk associated with a merger.

There are a number of drivers behind why JVs are used so extensively within the sector:

- Capital intensive: upstream projects can be too big for a single company (even a super-major) to finance on its own. Many of the larger liquid natural gas (LNG) and deep water projects fall into this category.

- Risk concentration: the risk profile attached to large-scale exploration and production (E&P) projects is such that no single company may wish to take full exposure.

- Access to technology: complex or frontier developments may require proprietary technology that requires the owner to have a stake.

- Access to resources: the legal owner of resources may not have the capital/technological ability to develop them to their maximum potential.

- Supply chain optimization: downstream supply chains may be optimized across disparate geographies by pooling assets. Many of the refining JVs are based upon supply chain and market supply optimization for the various participants.

- Market positioning/Portfolio optimization: pooling assets may allow the JV to develop a market-leading position in a particular geography (downstream) or product (chemicals) and enable a portfolio to be optimized across both asset pools, generating a value uplift from prioritizing larger assets. In an increasingly cost-focused climate, economies of scale are critical to success. Partnering may help achieve these.

- Regulatory requirement: some countries require foreign companies to partner with local entities if they are to enter that market.

- Political sensitivity of energy security: this means that JVs as opposed to acquisitions/takeovers may be more appropriate.

Past, current and future trends

The past few years have seen high numbers of oil and gas JVs being entered into, particularly in the upstream where the cost, risk, and technology issues clearly favors a collaborative approach on the largest projects.

The reduction in the number of JVs in 2009 could be a result of companies focusing on cost cutting and maintaining funding for existing projects as opposed to starting new projects.

It could also be due to the fact that the management of JVs is both risky and time consuming.

Much research has been completed on the subject of JVs and their performance. The results are mixed with many studies suggesting that they have high failure and inefficiency rates e.g. 30-70% of JVs have problems of inefficiency and bad performance, and about 50% of the ventures fail due to high cost (Kogut, 1988; Bleeke and Ernst, 1993). Other studies show a failure rate of 30% to 61%, and that 60% failed to start or faded away within five years (Osborn, 2003).

Despite this recent downturn in the number of JVs, the current market conditions could indicate that we are about to see an upturn in the numbers being entered into.

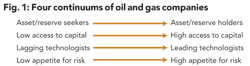

Oil and gas companies can be positioned somewhere along each of the four continuums shown in Figure 1.

If an oil and gas company is on the right hand side of all four continuums, then they may have no need to partner and may wish to proceed with a project as a sole venturer. If, however, it is positioned towards the left hand side of any of these continuums then it may well be necessary or appropriate for it to partner.

The downturn and the flight from risk in the capital markets means that many companies will have moved significantly to the left on the 'Capital Access' continuum. This is especially true for many of the small- to mid-cap exploration and production companies and a number of the national oil companies (NOCs). In the current climate of uncertainty, many companies, and their capital providers, may also have moved significantly to the left on the appetite for risk continuum.

The recovery in the oil price to around $60 to $80 per barrel means that there are now a broader range of projects that have become economically viable. These projects are often in deepwater or are in locations remote from the markets that they will supply. Both factors mean that large scale capital investment will be required to develop and commercialize them. Again these types of project favor a collaborative approach.

We are already seeing these trends in the market place with Petrobras partnering with a number of companies to develop its deepwater finds off the coast of Brazil in the Campos and Santos basins and Russia making positive noises regarding partnering on Sakhalin 3 and 4.

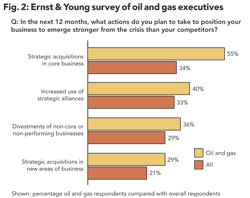

These factors could well provide the necessary stimulus for JVs to return to the levels that we have seen in previous years. In a recent Ernst & Young / Economist Intelligence Unit survey, it was revealed that 40% of the oil and gas executives surveyed believed that they would be planning an increased number of strategic alliances over the next 12 months.

We are already starting to see the early signs of increased JV activity in the market place with a number of recent announcements.

As these transactions take place, companies should keep a few critical success factors for JVs in mind.

- Transparency, openness and honesty between the partners

- Thorough financial and tax planning

- Consideration of all potential dissolution scenarios

- A robust legal agreement that contains provision for all of the above

JVs are an inherent part of the oil and gas industry and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. When managed well, they can deliver real value to all stakeholders. However, when things go wrong, they have the potential to destroy shareholder value, with arbitration and legal proceedings being a costly, time consuming distraction for the management of both the JV and the partners.

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com