Endless Saudi oil: miracle or mirage?

Don Stowers

Editor, OGFJ

As steward of 25 percent of the world’s proved oil reserves, Saudi Arabia has an excellent track record. This is the prevailing view among industry observers. For most of the past 70-plus years since oil was found in the desert sands of the Arabian peninsula, they say the Middle Eastern kingdom has been an advocate for fair pricing and has been willing to adjust its production and exports to prevent global shortages and resulting price spikes. In addition, the kingdom and its national oil company, Saudi Aramco, have employed the latest technology to maximize the production and longevity of its massive fields.

As the world’s major oil exporter and a founding member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Saudi Arabia has long exercised a measure of control over the commodity that drives the world’s economies. However, as worldwide consumption of petroleum products has risen and supplies have struggled to keep up with demand, OPEC and Saudi Arabia have seen their role in setting oil prices dwindle.

Although curbing oil exports would surely cause prices to climb, OPEC member countries do not have the capacity to ramp up exports to prevent escalating prices, as have been seen in the past year. The waning influence of OPEC has even caused some to question whether or not the organization has outlived its usefulness.

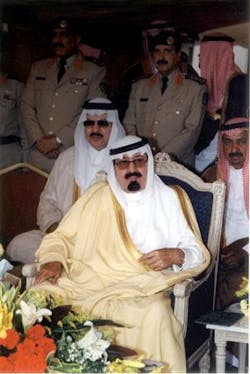

In light of these changing circumstances, created in large part by greater industrialization and improving economies in China and India as well as the incessant appetite for gasoline and diesel fuels to power American vehicles, industry observers and analysts have been speculating how the role of Saudi Arabia may change under its new king, Abdullah, who assumed power in early August following the death of King Fahd, his half-brother.

Abdullah, 81, had served as de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia since Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke in 1995. He is regarded as an effective administrator and is generally viewed as pro-Western in his political outlook, particularly since extremist elements began targeting oil installations with bombs and kidnapping and murdering foreign workers and Saudi nationals alike. Government resolve also increased after it was learned that members of the royal family themselves were on Al-Qaeda’s “hit list.”

Will Saudi oil policy change?

In light of these developments, it is prudent to ask how the transition in power in Saudi Arabia will impact the petroleum industry there and what the effect will be on world energy markets.

Ann-Louise Hittle, head of macro energy for Wood Mackenzie, the international research and consulting company headquartered in Edinburgh, had this to say about the regime change in Saudi Arabia:

“We do not expect a significant change in oil policy with the new king, Abdullah, who has acted as regent the last 10 years after King Fahd’s stroke. King Abdullah is not likely to aspire for higher oil prices as some fear, rather he seeks a goal of maximized prices at a level that does not spur investment in alternative forms of energy nor undermine world economic growth. The target price appears to be in a range of $40 to $50 per barrel.

“. . .Higher revenues have improved domestic stability in Saudi Arabia and, indirectly, benefited consuming nations by reducing the threat to Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities from terrorism and civil disorder.”

Hittle added, “As regent, King Abdullah has pursued a policy of improving relations with the United States. This can result in steps to drive down oil prices when they move above $60 per barrel, as was the case in May 2005, although the effectiveness of such steps is constrained by tight capacity.”

Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) expressed similar views in a comment issued shortly after the death of King Fahd. The Massachusetts-based organization said it expected a smooth succession in Saudi Arabia, but longer-term challenges for the new monarch, among them the prospect of returning Saudi insurgents from Iraq, who may be a source of potential instability.

Otherwise, CERA does not expect Saudi oil policy to be affected by the transition but it does expect Abdullah to continue the process of gradual reform.

Other questions that beg an answer are:

• Are Saudi oil fields in danger of serious production declines?

• Can technology extend the life of these fields?

• Are there new, undiscovered fields in the Saudi desert or offshore?

• When will Saudi production peak?

• Will Abdullah move forward with privatization of the petroleum industry and could this help rescue aging fields and establish new ones?

Saudi Aramco and the government of Saudi Arabia have been overwhelmingly positive in their public statements about the longevity of Saudi reserves and the country’s capacity to increase production to meet rising demand. Some industry analysts have supported that position.

Simmons expresses concerns

Others, among them Matthew R. Simmons, head of Houston-based investment bank Simmons & Company International, have raised concerns about the ability of Saudi Arabia to raise oil output and have questioned what they call the “lack of solid data” from OPEC producers, including Saudi Arabia.

In a presentation to the Hudson Institute in Washington, DC, in July 2004, Simmons said that “trust me” is the only proof for Saudi Arabia’s oil outlook and that his own analysis of more than 200 SPE papers on Saudi Arabian oil is “troubling.”

Specifically, Simmons noted that:

• Only five to seven oil fields produce 90 percent to 95 percent of Saudi oil output;

• The giant Ghawar field accounts for 60 percent of the output;

• All but two key fields are extremely old;

• Intense water drive/water injection masks normal depletion;

• Unannounced, high reservoir pressures will end;

• Intensive exploration efforts have failed to find much added oil; and

• Lack of verified data leaves the world in the dark about Saudi reserves.

The Saudi response to these concerns is that:

• Current oil output can reach 10.5 million barrels per day;

• Original oil has grown by 20 percent in 20 years;

• Proved oil reserves are “a conservative 260 billion barrels”;

• There are still 200 billion barrels of undiscovered oil;

• Finding and development costs are low ($0.50/bbl);

• Saudi Aramco’s use of new technologies is exemplary; and

• The kingdom can safely produce 10 to 15 million barrels per day for the next 50 years.

Simmons says that if he is right about Saudi oil production and the official rebuttal is wrong, no other country or supplier is capable of making up the loss in production if output is lost. He adds that advanced oilfield technology may be keeping well productivity high, but questions if this is sustainable or if technology is accelerating the last easily produced oil.

“If Ghawar experiences significant production declines, Saudi Arabia’s oil output will have peaked,” said Simmons. He added that if Saudi Arabia’s “oil miracle” begins to fade, the world has no “Plan B” prepared.

Role of Saudi Aramco

Another well-known and respected analyst who asked not to be identified in this article commented, “It is hard to overstate the degree to which Saudi Aramco reaches into Saudi Arabian society. Imagine a much bigger, stronger version of Pemex or PDVSA.”

Aramco takes a great deal of pride in its technical proficiency, said the analyst. They rightly believe they are on the cutting edge of technology and their oil field practices are state-of-the-art, including Aramco practices in horizontal drilling, well completion technology, and dealing with water encroachment.

He said that the actual unemployment rate in Saudi Arabia is “somewhere between 18 and 30 percent” [the official estimate is 13 percent], although many do not want jobs and are not seeking employment. The percentage of the population under the age of 20 is 60 percent or greater, he said.

There are about 5.6 million foreign nationals [among a population currently estimated at 26.4 million] living in Saudi Arabia, primarily from South Asia, many of whom have been brought in to perform jobs that Saudi citizens were apparently unwilling or unable to do.

“It is hard for [Westerners] to understand their culture, but many people there have a sense of entitlement, that the government with its oil wealth will take care of them. By our measure, it is a dysfunctional society lacking a work ethic. By theirs, there is a sort of cultural continuity,” he added.

Saudi-US relations ‘strong’

Speaking at the James Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston on May 16, Saudi Aramco president and CEO Abdallah S. Jum’ah talked about the “close ties and partnership” that have developed between his country and the US dating from 1933 when Saudi Arabia and Standard Oil of California, predecessor to Chevron Corp., signed an agreement paving the way for the development of the oil industry in the kingdom.

For decades thereafter, said Jum’ah, Aramco was a partnership among four major American oil companies that worked closely with the Saudi government to develop the kingdom’s oil resources. Those companies and the tens of thousands of Americans who have worked at Aramco, made tremendous contributions to the country and its prosperity, he added.

Today, approximately 35,000 US citizens live and work in Saudi Arabia, making it one of the largest overseas communities of Americans anywhere in the world.

“I think the best days of our economic partnership still lie ahead of us,” said Jum’ah. “There are a wide range of profitable investment opportunities in the kingdom available to American companies, whether Fortune 500 firms or small- and medium-sized enterprises.”

He cited telecommunications, power generation, water desalination, refining, petrochemical, natural gas, engineering, construction, and service industries - but did not specifically mention the upstream E&P sector, which his company currently controls on an exclusive basis.

As evidence of Saudi Arabia’s ability to continue to supply US and world demand for oil, Jum’ah said that proven reserves amount to some 260 billion barrels, a quarter of the world’s proven reserves. He “conservatively” estimates probable and possible reserves at 100 billion barrels. Finally, he says the country has yet-to-be-discovered resources that he believes to be another 200 billion barrels.

He adds that Aramco’s reservoir management teams aren’t merely looking at the next decade or two, but rather at production strategies 50 years from now.

Saudi minister: reserves growing

Speaking at the World Affairs Council in San Francisco on May 24, Ali Al-Naimi, Saudi Arabia’s minister of petroleum and mineral resources, was bullish on his country’s ability to provide a continual supply of oil to the world.

“There is no need to panic,” he said. “The world is not running out of oil any time soon.”

He went on, “In the early 1970s, some people predicted that the world was fast approaching an era of oil scarcity. During this period when we were supposed to be running out of oil, world oil reserves continued to grow, from about 550 billion barrels in 1970 to more than 1.2 trillion barrels today. This increase is all the more remarkable given the fact that the world consumed 800 billion barrels during this period.

“In the case of Saudi Arabia, our proven reserves were estimated to be about 88 billion barrels in 1970. Today, we conservatively estimate them at more than 264 billion barrels, despite the intervening 35 years of production. Last year alone we added more than 1.5 billion barrels to reserves, despite having produced over three billion barrels during this period.”

Al-Naimi added that he believes there are “vast quantities” of conventional and unconventional oil resources remaining to be exploited and that using technology to increase the recovery rate by only one percent provides an additional 70 billion barrels of recoverable reserves.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that King Abdullah faces some serious challenges during his reign, among them reformers who would prefer a constitutional monarchy that would limit the power of the king; fundamentalist forces who despise the monarchy and seek a government run by Islamist clerics; infighting among the 3,000-strong royal family as to the line of succession; and the question as to how long oil production can continue at its present rate and if it can be increased to meet growing world demand.

All of these are serious concerns for the Saudi government and the world community. Of these, major terrorist attacks on Saudi Arabian oil installations could undermine the Saudi government and inflict serious damage on the international economy through a surge in the price of oil. The loss of this supply for even a relatively short time could conceivably throw the world into a global recession. OGFJ