Special Report: Oil and Gas investment in Russia: time to review the risk?

Mark L. Robinson

Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

McLean, Va.

Until recently, there was hope that Russia would liberalize its energy sector and rely much more heavily on foreign capital, technology, and know-how. However, the role of private capital was called into question by the arrest of Russian businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky and by other government actions curtailing activity by private interests.

The reality of limits has been confirmed by the Putin government’s new policy on developing oil and gas fields. The Ministry of Natural Resources recently announced that the government will offer licenses to develop 250 oil and gas fields this year, six of which will be categorized as “strategic” and therefore limited to joint ventures in which Russian partners hold at least a 51 percent share.

The message seems to be that the government will keep a close eye on the Russian energy sector, and access to the most desirable resources will come only with special conditions. Although the country remains high on the list of places with promise, these messages should require foreign companies to revise their thinking about Russia.

The recent government announcement will increase the number of assets that foreign firms can pursue and gives them a chance to secure a share of proven reserves that by some estimates may total between 60 and 200 billion barrels of oil and over 1,500 trillion cubic feet of gas. This represents a huge opportunity for oil and gas companies that are not already active in the region.

Although business risks continue and future events cannot be accurately predicted, there are a few conclusions that can be reasonably made:

• According to the International Energy Agency, investments required to maintain and grow Russia’s energy infrastructure will total some $935 billion between now and the year 2030. A significant amount of investment will come from multi-national loans and international corporations.

• Russia’s oil and gas industry will continue to be dominated by a small group of vertically integrated oil and gas companies, some with significant foreign ownership. The government will continue to exercise significant influence via its control of the Transneft oil pipeline monopoly and its strategic shareholding in Gazprom which controls the gas pipelines.

• Foreign investment opportunities will be available, but controlled.

• China and India, with their rapidly expanding economies, will continue to increase their energy investment funds in Russia to fill the need for their growing energy imports.

Recent developments have added new complexities, challenges, and uncertainties about future directions for Russia’s energy sector policies. Exactly what role foreign companies will be able to play and what policies will govern their participation remain unclear. Moreover, there is little reason to believe these issues will be clarified any time soon.

As with any new venture, companies looking to participate in the future of Russia’s oil and gas industry will need to develop an investment and territory entry plan that includes an in-depth assessment of multiple scenarios regarding the political and economic climate, the legal framework under which the company would operate, taxes and royalties (especially wellhead and export taxes), and the level of risk. The variety of potential business environments should influence companies’ due diligence plan for evaluating potential energy partners.

In this article, we examine the importance of Russia in the global energy economy, the evolution of investments in its oil and gas industry, where the industry may be headed, and the use of a strategic flexibility process for mitigating future risk.

Russia’s role in global energy

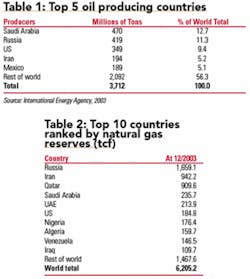

In terms of oil and gas, Russia is a country with enormous energy resources. Because it holds the world’s largest proven natural gas reserves and the seventh-largest oil reserves, Russia plays a critical role in the global energy market.

Since 2001, Russia’s increases in crude oil production have more than matched increases in China’s demand. Further, Russia is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of natural gas, providing close to one-fourth of the requirements of European countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Russia supplies nearly one-third of the natural gas needs of the growing economies of Eastern Europe and the Baltic states.

Gazprom: Russia’s energy giant

The world’s largest gas company, Gazprom holds more than 20 percent of the world’s total gas reserves, and in 2004 produced close to 80 percent of Russia’s total gas output. The company’s supplier position in Eastern Europe is remarkable. Gazprom provides approximately 91 percent of Hungary’s gas imports, 79 percent of Poland’s, and nearly 75 percent of the Czech Republic’s.

In Western Europe, Gazprom supplies about one-fourth of the region’s natural gas. Based on its size, production capabilities, and market position, the Russian government is reinforcing Gazprom’s position as an international energy giant.

Gazprom is currently looking beyond Europe to America and Asia and has targeted the development of LNG projects as part of an ambitious expansion plan. The company recently signed memorandums of understanding with a number of international firms such as Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Statoil, and Petro-Canada regarding the development of the giant Shtokman field, and is also involved in several large pipeline projects.

Foreign companies that wish to gain access to Russian gas will have to partner with Gazprom based upon its size, pipeline connections, and reserves. The company will rely on international firms to supply the substantial funding for project development and infrastructure costs.

The race for Russian hydrocarbons

During late 2004 and early 2005, oil prices on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) traded at all-time highs of over $55 per barrel. Some analysts, including Goldman Sachs, are even predicting oil prices in excess of $100 per barrel within a short period. Reasons given by analysts for the high price include supply disruptions brought about by weather, oil worker strikes, trading speculators, and the ‘terror premium.’

Demand from growing economies such as China and India also has led to the increase in the price of oil. In a classic example of the laws of supply and demand at work, huge growth in these countries’ need to import oil has put significant upward pressure on prices. While each country has relied on the Middle East for the bulk of oil imports, additional supplies are coming from Russia.

India. Through its 95 percent ownership of the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), India is using a variety of strategies to develop Russian oil and gas assets. ONGC owns a 20 percent share in the development of the Sakhalin-1 operated by ExxonMobil and is reportedly close to finalizing a deal with Russia’s Rosneft to bid jointly for operator status of the Sakhalin-3 project. ONGC is also interested in acquiring a 15 to 20 percent stake in Yuganskneftegaz, the production arm of Yukos.

China. China relies on the Middle East for approximately 40 percent of its crude oil imports and is negotiating with Russian firms on a number of initiatives. It is competing with India’s state-owned oil company ONGC to obtain an equity stake in Yuganskneftegaz and has advanced Rosneft $6 billion in return for 48 million tons of crude oil by the year 2010.

Japan. In a race to obtain additional oil supplies, Japan’s proposal to build a 2,700-mile pipeline across Siberia into northeast Asia was selected by Russia over a competing plan by China. Japan plans to bankroll not only the construction of the pipeline - $5 billion by some estimates - but also invest $7 billion in exploration and development costs with an additional $2 billion to be spent on social projects. The Chinese had anticipated the pipeline ending in the refining capital of Daqing, but Japan’s ability to provide the necessary capital and geographical access to international markets was responsible for their winning the project, as was the promise of creating more construction jobs - all in Russia. Japanese companies are also heavily involved in the Sakhalin-2 project.

Russian evolution

In light of Russia’s current investment climate, it is worth reviewing the historical context of Russia’s oil and gas industry. The political and economic reforms in Russia during the early 1990s came about by advisers brought in under then-president Boris Yeltsin.

Sensing that the general population felt that reforms weren’t progressing, Yeltsin’s advisory team accelerated the process by selling off state assets and enterprises at prices that were arguably lower than their actual value. Some of Russia’s most valuable resources were auctioned off by banks owned by the oligarchs under a scheme called “Loans for Shares.” In many cases, the banks ended up as the winning bidders.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian oil and gas sector opened up to foreign investment beginning with the exploration of large undeveloped resources. As part of its energy investment strategy, the country adopted an underground, or subsoil, law in February 1992 that defined the government’s ownership of the country’s natural resources and detailed how they would be developed.

Under the law, the government would own all of the country’s oil, gas, and mineral deposits and would make them available by auction to foreign investors for exploration and extraction. In return, the government would receive royalties and tax payments.

Detailed implementation laws and regulations were lacking however. The law was enacted just prior to the establishment of a 50:50 joint venture - the Polar Lights Company, between ConocoPhillips and Lukoil - for the development of the Ardalin field in the Timan-Pechora basin some 1,000 miles northeast of Moscow.

Even with the subsoil law being enacted, Russia’s oil and gas production was declining and without a workable legal and fiscal regime, the country would be unable to attract the necessary foreign investment to increase production, much less develop greenfield projects. Foreign capital was needed at the time because the Russian oil companies were only starting to emerge and didn’t yet have the financial muscle to develop these projects themselves.

In the search for a model that would attract foreign investment, Russia, with input from outside experts, settled for a production sharing agreement (PSA) regime. A PSA is a legal agreement between a government and investor that provides for:

• reimbursement for field development costs out of proceeds from hydrocarbon sales;

• division of profits (i.e., after recovery of costs) with the state;

• payment of corporate income tax from the contractor’s share of production; and

• a stable contract environment protecting the contractor from law changes and setting tax rates and royalty payments for the entire term of the agreement.

The mid-1990s saw the start of expensive and technically challenging exploration and development projects with Russia signing three production sharing agreements with international firms: Sakhalin-1 and 2, and the Kharyaga project in Siberia. Foreign companies such as ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch/Shell and Total SA of France led the way in developing these oil and gas projects with additional participation from Japan and India.

While PSA arrangements proved to be an attractive method for foreign firms to invest billions in Russia’s oil and gas industry, they were unpopular with the emerging Russian oil companies that believed PSAs gave foreign firms a competitive advantage.

Russian companies typically had more mature fields that were easier to develop while foreign companies had the newer and more difficult projects. After intense lobbying efforts by Russia’s domestic producers, the PSA structure was relegated to a small list of fields approved by the state Duma (legislative body).

With an increasingly favorable business climate beginning to emerge during President Vladimir Putin’s first term in office, foreign firms purchased assets in Russian oil and gas firms. Unique among these was the completion of a 50:50 joint venture between Russia’s TNK, and British oil super major BP to form TNK-BP. The deal cost BP an unprecedented US$6.35 billion.

Other announced and completed acquisitions include: Total SA’s intention to acquire a 25 percent stake in Russian gas producer Novatek for $1 billion; ConocoPhillips’s completed 7.6 percent stake in Lukoil for $2.36 billion; and Marathon Oil’s acquisition of Khanty Mansiysk Oil Corp. for $275 million.

The winds of political change

In mid-2003, Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky was arrested and jailed in a move that many saw as an attempt by the Kremlin to curb his growing influence in politics. The subsequent attacks by the tax authorities on Yukos may have been seen as manifesting a dramatic shift in how Russia plans to conduct business in the energy sector.

In early 2004, the Russian government announced the annulment of a tender - originally won in 1993 by ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Russian firm Rosneft - for the rights to develop one of the three Sakhalin-3 parcels, the choice Kirinsky block. This block, the largest of the project’s three, has estimated reserves of 453 million tons of extractable oil and close to 700 billion cubic meters of gas.

While the cancellation of the tender was seen as unfair to the firms involved, followers of Russian political analysts have drawn attention to the ways in which President Putin laid out the foundation for a new Russian energy industry in a number of public statements.

During his studies at St. Petersburg’s State Mining Institute in the mid-1990s, Putin wrote a candidate of science dissertation on the topic of using mineral and other natural resources as a core strategy for the development of the Russian economy. In an abstract that appeared in “Notes of the Mining Institute” in 1999, he laid the groundwork for the changes now occurring in Russia.

In his discussion, Putin describes the use of the country’s oil, gas, and mining base as a way to secure not only Russia’s economic development, but also - and more importantly - the country’s international position. In a strongly worded, uncompromising tone, Putin writes that the state would dictate the ways in which the oil and gas industry would operate. Russia cannot limit itself to be solely an exporter of raw and unfinished materials, Putin writes, but must develop a national processing industry to become a leading economic power.

As the paper concludes, the future Russian president writes that the government should take steps to both develop and increase the international market position of state-owned enterprises in the oil and gas sector.

The stalled merger between gas monopoly Gazprom and its oil counterpart, Rosneft, is a critical component of this goal. This merger, if and when completed, will create a state-owned company with estimated oil and gas reserves of 117 billion boe - five times that of ExxonMobil. The government has said that it will take a 51 percent ownership in the new company, thereby preventing foreign firms from owning a majority share in a key Russian energy firm.

In a rare interview that appeared in the New York Times in late 2003, Putin declared himself to be a supporter of “managed democracy.” This approach is consistent with his philosophy of strengthening not only the presidency, but also the enhancement of state-owned enterprises.

By reorganizing government-owned oil and gas firms, Russia hopes to create an energy industry on par with the international majors. Once this reorganization is complete and national interests firmly secured, it is anticipated that foreign firms will have a definable path to participate in the Russian oil and gas market.

Unpredictable business environment

Although there have been developments that have increased foreign firms’ access to Russia’s energy sector and improved the investment climate, Russia’s recent past has also been marked by a lack of consistent policy, reversals of set policies, and some unexpected turns away from liberalization.

Furthermore, there are serious challenges in forecasting what the future may hold. For example, President Putin is scheduled to leave office in 2008, and it is difficult to know at this stage what administration might succeed him. Some political analysts claim that new challengers could emerge prior to the election, with agendas that differ from each other’s and from the current government’s.

There are thus important questions about how the change in administration might affect energy policy decisions and foreign investment rules. These uncertainties are compounded by speculation of an effort to enable President Putin to run again.

A strategic dilemma

Despite some developments that seem to clarify the situation, at least in the short term, much is still uncertain about Russia’s oil and gas industry. Energy companies are thus likely to be caught unprepared for political and economic developments that could render their current strategies obsolete.

One way to handle this problem is to use traditional scenario planning techniques that attempt to manage all risks and possible outcomes. Another is to excel at predicting how the market will evolve. Yet another approach is to push ahead with the expectation that changes will be required, while believing that the company has sufficient agility to react to whatever surprises may emerge. None of these approaches, however, provides for a foolproof solution.

Even if a firm has developed a scenario for every potential market event, the response is likely to be thin. Studies have shown that many predictions about future events are off or outright wrong. Given the fact that many energy investments are large in scale and entail long development cycles, even a quick response will have its limitations.

Strategic Flexibility framework

Deloitte Research has developed a framework called Strategic Flexibility to cope with the uncertainty of the future marketplace. This approach allows a company to compete effectively today while being prepared to respond to future events.

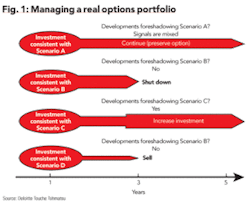

Strategic Flexibility involves using traditional scenario building techniques to anticipate and prepare for alternative market events while defining a strategy that includes actions that will be appropriate regardless of which scenario actual events resemble. Real options concepts are used to plan contingent arrangements for elements of the strategy that will be needed under some circumstances but not others.

In using traditional scenario-based planning, a company defines a set of scenarios that identifies the full range of plausible futures. The company then adopts a core strategy that will work in as many of the scenarios as possible. With respect to the potential developments that are included in the scenarios but not addressed by the robust strategy, the company holds off. It waits until unfolding events signal which of these other scenario conditions are materializing before committing the extra money and effort needed to deal with them.

Strategic Flexibility differs from this approach in that a company not only moves forward with the “no regrets” initiatives, but also makes limited investments in assets and capabilities that would be advantageous in some scenarios but not others. These arrangements include a provision for increasing or decreasing the level of commitment.

Obtaining the right to invest more or pull back will cost more, but in many cases the added flexibility will justify the extra expense. This is an application of real options theory: as with an investor who holds financial options, the company applying Strategic Flexibility has the right, but not the obligation, to commit to full ownership.

Strategic Flexibility can be helpful in evaluating Russia’s uncertain energy investment climate. Given questions about fundamental issues such as future foreign investment rules, resource development policies, and political stability, a new and more effective framework for managing strategic risk is required. Scenarios provide a means of defining the range of plausible alternative futures. Real options supply the mechanism for making provision for conditions that could, but may not emerge.

With respect to the Russian energy sector, creating real options might involve measures such as buying a piece of a Russian oil and gas company, or E&P venture, or LNG facility, or establishing a joint venture - in each case with the right to ratchet the investment up or down, or to exit altogether. The option price is the cost of acquiring the asset. The “strike price” is the incremental cost associated with activation - buying more of the company, or funding more of a project. The option would be exercised when the cash flow exceeds the cost.

Strategic Flexibility in action

The Strategic Flexibility framework in real-world applications serves to provide a way to sort through the myriad of possibilities and identify a manageable number of investment opportunities that hedge the most significant and likely future outcomes. These initial investments are intended to be small, but “small” is a relative term that depends upon a number of criteria that include the financial strength of the company involved and the amount of funds that it makes available for an investment.

As an example, an initial investment made by an oil major may total hundreds of millions of dollars, whereas a large independent firm could decide to make an up-front commitment costing tens of millions of dollars. The key element of a real option is its leverage structure such that when certain conditions are met, the follow-on investment must exceed the initial investment, sometimes by a significant amount.

In the real world, an initial investment of $10 million that creates an option to avoid unnecessarily committing an additional $10,000 is not much of an option. When market signals indicate that a much-desired scenario is likely to unfold, the initial investment of $10 million may require a follow-on investment of $100 million. By contrast, a $25 million up-front commitment that saves a misapplication of $250 million illustrates the true flexibility of investment options that lie at the core of the Strategic Flexibility framework.

Using the Strategic Flexibility process in Russia can be applied to investment decisions now facing many firms: the uncertainties surrounding the viability of building a domestic oil and gas business versus an export production play. A company could make a major commitment to E&P in Russia, but use Strategic Flexibility with respect to investments that pertain to the export versus domestic market.

The investor might make contingent investments in infrastructure for transporting product out of the country, and also in infrastructure for distributing product within the country. Over the next three to five years, as events unfold and it becomes clearer under what circumstances the Russians will allow exportation, or serving the Russian market becomes attractive, the company could adjust its investments accordingly.

With that said, Strategic Flexibility won’t necessarily work in every circumstance. The key criteria for applying the framework are whether the investment can be staged and how soon a total commitment is essential. Strategic Flexibility is best used where it is possible to proceed in a series of steps and where the business environment is such that it will take 12 to 36 months before all of the pieces have to be in place.

In cases where it’s critical to be in play now with a major financial commitment, Strategic Flexibility may not be practical. Being able to identify clearly the circumstances in which Strategic Flexibility is an appropriate tool is critical.

Future investment opportunities

While the uncertainties that make it so difficult to predict the future business environment in the Russian energy sector might be daunting, the use of Strategic Flexibility can mitigate risk and make doing business in Russia more feasible. Some points to consider when using the Strategic Flexibility approach:

• Although the last 10 years has seen massive consolidation in the Russian oil and gas sector, there may be as many as 400 small and mid-sized Russian companies that could represent future investment targets.

• The Russian government needs financially stable oil companies to provide substantial funding and technical expertise for the forthcoming Sakhalin-3 and Shtokman projects as they did for Sakhalin-1 and Sakhalin-2.

• The stalled merger between Gazprom and Rosneft may portend a period of further industry consolidation that will create new entities and make merged companies more attractive to outside investors.

• Russian majors may be looking for opportunities to rationalize their asset portfolios.

• Opportunities may exist in oil and gas infrastructure projects if monopolies are liberalized.

• The latest draft law revision on subsoil use may not apply to the development of offshore assets, which may indicate the availability of additional projects.

• New opportunities will come from developments in Russia’s burgeoning LNG industry which requires substantial investments in liquefaction plants.

• Additional capacity will need to come from greenfield developments in portions of East and West Siberia, the Timan-Pechora area, and Russia’s Far East.

Old Russian fields should not be completely written off. By employing good oilfield practices, some experts believe that a one percent improvement in recovery rates may add up to 700 million barrels to reserves.

Conclusion

Adjusting corporate strategy to allow for alternative possibilities in Russia’s oil and gas industry presents challenges since it is not feasible to prepare fully for all future scenarios, nor is it possible to make quick alterations to projects that require sizeable investments and long lead times. By applying the principles of Strategic Flexibility, companies can develop a corporate strategy and manage risks in order to avoid being surprised by developments in Russia’s oil and gas industry. OGFJ

The author

Mark L. Robinson ([email protected]) is an energy analyst with Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu in the Global Energy & Resources practice. He is also a member of Deloitte’s Intellectual Capital Committee. Robinson served in a similar role with the former Mobil Oil Corp. He holds an MBA from Marymount University.