Politics and the oil industry

How to build community support for pipelines and hydraulic fracturing

Travis Sexton, The Saint Consulting Group, San Ramon, Calif.

The prominent coverage of widespread opposition to hydraulic fracturing projects from Ohio to California has taken a new turn recently as opponents who cannot stop the fracking now try to impose local bans on pipelines to prevent transport of natural gas liquids from shale sites to midstream or downstream destinations.

Companies that thought they had achieved some measure of control at drilling sites find now more than ever they have to think through strategically the political risks at all stages – from soup to nuts – that arise from extracting energy, refining or processing it, and taking it to market. Despite the growth in our home-grown energy industry and its positive economic impact, political risks for pipelines and fracking have also grown. More sophisticated opponents in land-use politics require an organizing approach for building community support for this industry.

The opposition is not just a reaction to fracking. Nearly four out of five Americans oppose any type of development in their community. The Saint Index, our annual survey of national attitudes on land development, has found that drilling and pipeline projects actually generate less opposition in local communities than quarries, casinos or landfills.

Yet article after article describes opposition to oil and natural gas companies for drilling or pipelines permits, or referendum battles, particularly in Colorado and Kentucky, where opponents seek local bans on pipelines many miles from shale sites as the new way to curtail such exploration. As far as permitting new projects, this is the new normal.

Be proactive

The new normal requires a different kind of strategy to anticipate and get out in front of the opposition in the battle for public opinion. Think of it this way. To succeed in today's permitting climate, identify who your neighbors will be and engage with them about your project before the opposition sets the table. As the industry has seen already in key states, losing even one permit is much more costly than if the industry players beat the opposition to the punch. Where you find support then, you must harness and mobilize it in support of your position. Those who work tirelessly to kill your project are using a similar approach and their own set of tactics. It is time that you approached the process in a similar way because when residents are educated first, it cuts off the ability of the opposition to use deceit to attract stakeholders to their position.

When a reporter asked Chevron CEO John Watson last year what he had learned from Keystone XL pipeline opponents, he replied: "We have to do a better job of educating the community, we have to get out there earlier to identify and address concerns before the environmentalists get started." His advice was get out there, be early, be factual, and address peoples' concerns fully.

In taking the industry's case to the public, this article sets out a process for organizing community support at the local level, not at 30,000 feet but in the streets of communities where pipelines are proposed. When a pipeline proposes to carry natural gas liquids from shale sites through several states, one must consider a linear land-use strategy.

This is not a one size that fits all approach. Rather, it requires a process tailored to win over support in each of the many individual counties and municipalities where homeowners will be approached for easement negotiations, where elected officials will be lobbied by environmental groups, where Farm Bureau and other local bodies will want to understand the health, safety, environmental, and economic impacts of what is proposed.

What works in one community may not work in the next, and proper due diligence can identify the best tactics to suit each challenge. Failing to recognize this will impact your overall strategic objectives. All politics is local, and all planning is political. That is our starting point.

Watson's advice is suitable for this type of land-use battles, and peoples' concerns can vary. Public participation is on the rise and in too many cases the non-applicant participants are led by the opposition. Without an infusion of supportive voices, vocal advocates who understand the benefits and are vested in the outcome of the projects, the new normal suggests that many pipeline and fracking projects across the board could be delayed or defeated.

Advocacy Pyramid

Mobilizing grassroots advocates is necessary when navigating the process of permitting your project. Outreach is now essential whether you are a public or a private entity. So, when considering approaches to outreach, it is crucial that you choose an approach that allows for fluidity in the face of a continually changing public narrative.

You must also ensure that the approach prescribes a process-driven approach instead of a procedural-driven one. Viewing outreach through the lens of a procedural approach will create a series of discreet steps but ignores the fact that the system in place is dynamic and fluid itself. Instead, you must view outreach as a process or a series of procedures viewed as a whole with the end goal still being transforming identified supporters into vocal advocates for your project.

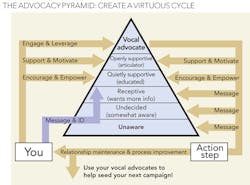

One approach to building public support is called the Advocacy Pyramid. Think of it as way to categorize people through a process. It assumes that every identified stakeholder has a right to share their opinion on the project at hand and to be educated by the applicant or developer of the project. The burden of education is on the applicant because the opposition will surely spend its time educating and setting the table of "facts."

Yet, the approach also focuses on ensuring that along the way of advancing an authentic outreach engagement, you can harness and mobilize vocal advocates. Their participation in the process is absolutely necessary. The advocacy pyramid is simple approach to help you illustrate public support for even the most controversial projects. Think of it as a process not a procedure. This approach is about action and seizing the moment. Remember, the outcome you are looking for is political action from vocal advocates – identify, engage, harness, and mobilize your support.

Building community support

When reaching out for community support, you will find a wide range of people – from those who are unaware, all the way up to those who are committed to support you. We call this an Advocacy Pyramid – everyone is somewhere along a Value and Quantity scale. The higher up the pyramid, the more valuable they are to your campaign; the wider the category, the more people are in that pool. Moving people up the scale from unaware to vocal support is how you get to "Yes."

Where are the NIMBYs? Not in this pyramid. Trying to convert opponents is a waste of time and resources. You can't ignore them, but your campaign is much better served focusing on people you can convert.

Your campaign to counter pipeline or fracking opposition should have two goals: move the unawares up to vocal advocates, and turn them out. Some unaware or undecided people do not care enough to pick a side. Those who are receptive need your help – give them information and persuade them. Approach this strategically as you would with any sensitive and controversial issue facing your company – do your due diligence, recognize and acknowledge the local concerns and rumors, such as eminent domain and local job creation, and tackle all misinformation in a straightforward manner.

Spend little energy per person on the bottom of the pyramid (use mass communications, low-context communications) and more energy for people higher up – face-to-face conversations, high-context communications.

This brings us to the Virtuous Cycle – the more information they get, the more they can effect change, and this is how people can be persuaded to become more openly supportive.

Aim to control the debate and drive the message. Flood the target community with your message, pumping traffic into the lower half of the pyramid. You can also run an initial voter ID program to identify as many possible and actual supporters as you can.

Vocal advocates should be engaged regularly; leveraging this group and guiding them to support and motivate, encouraging and empowering supporters, all further spread the message. At the action step – a city council hearing or a vote – they help carry the message.

The Advocacy Pyramid requires much effort and one-on-one interaction to build grassroots support for a project potentially as unpopular as pipelines or hydraulic fracturing. Most people who support a project do not feel strongly enough about it to publicly stand up against a neighbor. It is not a simple matter to organize public support when some citizens are adamantly opposed. In the case of a pipeline or energy exploration, it is essential. Failure to do so ensures defeat.

Identify

Since public participation is on the rise and we can all agree there is a passion gap between supporters and opponents, then you must identify all of the stakeholders you know and might expect to participate in the hearings or permitting process. Why? Because the law mandates that you should know some of them and the rest of the stakeholders expect us to. It is the right thing to do.

Let's move on from the position that you don't need to talk with your neighbors. Instead, create a stakeholder map that identifies all of those people reasonably expected to participate in the process. Once identified, map and rank them so you know how to engage. Building and managing an active database of stakeholders is one of your most critical steps in winning politically. Always remember that throughout the overall process, this step of identification is ongoing as the core piece of information that drives the process is: "Where does she stand on the project?"

Engage

Remember to start with the position that you are going to meet with those who deserve to participate in the process and have some sort of stake—whether it is safe streets, an investment or a property right. No longer can either a public or a private entity shirk its role as the prime mover to educate the community. And strategically think of each community as its own campaign that has its own unique local and political issues, objectives, and approval processes. Without engaging the community, one starts from a losing position within this new normal.

Harness

Undoubtedly, when developing a stakeholder map you will see that the opposition or watchdog infrastructure is much more robust. This means that you will need to build support infrastructure for a formal group of stakeholders to support you. Do not be shy about asking community supporters to form a group and advocate for the project publicly.

Mobilize

Mentioned earlier is this concept of a passion gap. Where it exists, the stakeholder on the supporter side needs more attention to take an action. Remember, mobilizing grassroots advocates is absolutely necessary in today's permitting environment and should be a key part of your strategy. The precursor to a supporter taking political action is constant engagement and communication by the applicant—to identify supporters and transform them into vocal advocates.

Process takes time

In taking all of this into consideration, it is also important to note that implementation of the advocacy pyramid takes a significant amount of time and commitment. People's opinions and concerns cannot be changed overnight. Nor can people be easily swayed through television commercials or glossy mailers. As with voters in a political campaign, people want to know that their opinions and concerns are both heard and taken into consideration before they will support you. It is a labor-intensive process but one that will provide greater value than waiting and reacting to the opposition.

About the author

Travis Sexton is division vice president, West Coast, for The Saint Consulting Group, a land-use political consultancy headquartered in Hingham, Mass., with offices in the US, Canada, and the United Kingdom. He can be reached at [email protected].