Merchant energy companies making slow recovery

Paula Dittrick

Senior Staff Writer

Oil & Gas Journal

Investor confidence has started returning to some integrated energy companies following a merchant energy sector collapse that stemmed in part from the California energy crisis of 2000-01 and in part from the Enron Corp. bankruptcy in December 2001.

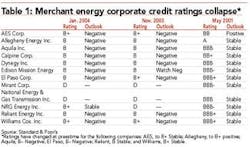

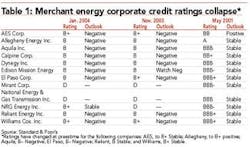

False price reporting debacles and trading scandals prompted many energy merchants to exit the trading business, while credit-rating agencies' downgrades prompted higher capital costs for the sector (Table 1). Meanwhile, stock prices of the energy merchant firms plummeted.

Natural gas trading has stabilized, but low electric power prices in some US regions and an overabundance of new power plants have shrunk these companies' revenues since the late 1990s.

Among others, Dynegy Inc., Williams Cos. Inc., and El Paso Corp. refinanced billions of dollars in debt, shed assets, restructured their core businesses, and hired new leadership in their individual struggles to survive.

Dynegy once had a merger agreement with Enron, but that agreement was terminated. Dynegy cited alleged breaches of representations, warranties, covenants, and other agreements in the aborted merger deal.

Consequently, Dynegy particularly was hard hit. However, the company's earning reports returned to black ink this year, following the implementation of a major financial restructuring and a redesigned corporate strategy.

Across the sector, integrated energy companies now emphasize more aggressive portfolio management than they did in the mid-to-late 1990s when the industry buzzword was "btu convergence."

The combined power-gas companies of the previous decade envisioned huge profits. Natural gas as future contracts started trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange in the early 1990s.

The convergence paradigm—set in motion by the US deregulation of electric power after the earlier natural gas deregulation—prompted an unprecedented series of mergers and acquisitions among gas pipeline companies, gas distribution companies, electric utilities, and merchant power producers.

"Pipelines expanded their systems to serve new loads, principally merchant power plants. Pipeline M&A hit a fever pitch. In a few years' time, what [had been] 20-30 pipelines could be counted on one hand. And the new energy merchants were the envy of all, making markets [and] managing risk until that bubble burst," said Sam Brothwell, an analyst with Merrill Lynch Global Securities Research & Economics Group in New York.

Enron invented the popular concept of high-growth energy merchants. "Of course, that model failed—spectacularly. By 2002, the pipelines that sought to emulate Enron almost followed it into Chapter 11," Brothwell said.

On July 16, Judge Arthur Gonzalez of the US Bankruptcy Court of the Southern District of New York confirmed the Enron reorganization plan. The former gas and trading giant that is slated to emerge from bankruptcy by yearend will be a fraction of what it was at its corporate heyday.

"Undoubtedly, this was an extremely complex bankruptcy," Stephen F. Cooper, acting Enron CEO and chief restructuring officer, said of the 900-page reorganization plan.

Enron is expected to change its name in 2 years after key assets are sold and creditors are paid.

Other merchant energy companies that filed for bankruptcy are NRG Energy Inc., Minneapolis; Mirant Corp., Atlanta; and National Energy & Gas Transmission Inc., Bethesda, Md.

Some gas-related companies still are recovering from their earlier energy merchant efforts. Many spent 2 years or more working to restore balance sheets and to wind down unprofitable, noncore businesses.

Btu convergence

Meanwhile, energy convergence continues to happen quietly, but not as the industry might have originally envisioned, analysts and consultants said.

"I think the convergence bug is still out there. We just have to look at it a little bit harder or think about it a little bit differently," said Dean Maschoff, a managing director in the energy practice at Navigant Consulting Inc. "You still have companies that are very interested in making the gas-power play connection happen."

Focusing on the US, every power company has its eye on natural gas markets and the role that gas prices play in power prices, he said.

Maschoff tells clients that an integrated energy business model remains workable.

"Anybody who comes from an integrated perspective is going to be thinking about both the gas and power model[s]. We are working with our clients to think in terms of a portfolio of asset positions," he said. "It's got to be both gas and power, and I think it is going to include both contract and regulated assets and perhaps some competitive merchant assets."

He advises clients to "look at the broad sweep of values in the value chain in terms of opportunities and to really understand where you bring value. In the power and gas side, you have to have a view as to how the industry consolidation plays out. You've got to be looking at opportunities, or at least keeping that on your radar."

Peter Rigby, a director with Standard & Poor's Ratings Services, said convergence has happened in the sense that the gas industry is crucial to the power sector. Gas increasingly is becoming the fuel at the margin, he said.

"Maybe convergence didn't happen in a way that a lot of people envisioned in terms of the oil and gas companies getting deeply entrenched in the power sector," Rigby said. "The power sector is a very different business from the oil industry. The oil industry is capital-intensive, but the power sector is even more soUand the power sector in the US is so susceptible to political and regulatory issues.

Oil and gas doesn't have to work within those kinds of conflicts. Power ultimately is a consumer product. The oil and gas sector doesn't get to the [energy] retail level.

"You don't see ExxonMobil Corp. power plants. That is just something that they don't want to do. They are happy producing gas, but they don't want to take the end-user risk," Rigby said.

Some oil companies expanded their trading functions when the merchant energy sector's collapse caused upheaval in gas and power markets. During that time, energy-trading practices were questioned and investigated by lawmakers and regulators.

BP PLC and ChevronTexaco Corp. were among oil and gas producers that helped fill a trading segment gap created by some merchant energy firms' exits from the physical trading business.

Gas markets

Even as the majors moved to overcome the gas trading turmoils of the last couple of years, they were planning to try to avoid possible future US gas shortages.

Cameron Byers, chief operating officer of BP PLC unit BP Energy Co., told a January conference at the University of Houston-Global Energy Management Institute (UH-GEMI) that the US gas industry faces continuing issues centering on supply, infrastructure, and market transparency.

Despite forecasts that US gas production cannot keep up with anticipated demand, he remains optimistic about the industry's ability to respond.

"There are clear signs of confidence returning to the (gas) marketsU. There is still a lot of work to do, but it feels like we are heading in the right direction," Byers said.

BP forecast that North American gas shortages could reach 10-14 bcfd by 2010, which emphasizes the need for finding additional supplies, he said.

"We should have confidence that the supply crunch will be solved if the market will continue to be allowed to work through the mechanisms of market pricing," said Byers. That should encourage investments in LNG facilities and US gas production, Byers said.

A power plant construction glut during the last 5 years built a scenario in which "the gas-fired generation industry will be depressed for a long time, in our opinion," he added.

Antonio Rodriguez, director of financial trading for ChevronTexaco also sees a gas market turnaround, but he notes that the cast of characters is shifting toward investors that have stronger balance sheets.

"The emerging industry achieved growth by adding liquidity to the market; however, there was an overextension of credit that the industry gave itself," Rodriguez told the UH-GEMI seminar. "The market share once enjoyed by the merchant energy companies is transferred over to the banks and also the majors, which now have to market their own production."

Consequently, most banks cannot handle the physical trades formerly managed by the merchant energy companies, so new participants are entering the scene.

"The market share is now composed of more-improved companies, which have much better credit ratingsU. Some trading has been taken over by the hedge funds, but that is a limited sector. They can only put so much money into this market. So what will happen then [is that] you will change some of the players," Rodriguez said.

New investors in assets

Some of the players making equity investments in physical assets also are changing.

For instance, a unit of insurance company American International Group Inc. agreed to buy 25 US power generation facilities from El Paso. Private equity funds have bought power plants and pipelines as well. Famed investor Warren Buffet's Berkshire Hathaway Inc. holding company acquired utility holding company MidAmerican Energy Holdings Co., Des Moines, in 2000 and followed that in 2002 with the purchase of Williams Cos.' Kern River Transmission Co. for $960 million in cash and debt. MidAmerican briefly this year also sought to develop a $6.3 billion gas pipeline from Alaska's North Slope to the Lower 48.

Meanwhile, no significant class of investors has emerged yet to invest in new power generation and transmission assets following the demise of Enron, Mirant, and NRG, said Energy Security Analysis Inc., Boston.

"Private equity firms are buying distressed assets; they are not building new ones," said Paul Flemming, ESAI's Power Analysis Services manager. Consequently, the value of assets in the distressed electric generation sector will become more volatile.

Some areas, like Texas and parts of New England, have electric surpluses that will endure for years, while other areas, like parts of California, have looming electric generation deficits and need investment now.

"These conditions provide enormous opportunities for investors who are willing to do their homework," said Edward N. Krapels, director of ESAI's Energy Development Services. "While there is not much investment in generation today, investment in transmission is taking off, and that will change the mosaic of asset values dramatically as regional access to capacity shifts."

Gradual recovery

For merchant energy survivors still endeavoring to heal themselves, the recovery process is slow, said Craig Pirrong, UH-GEMI energy markets director.

"First, there is substantial overcapacity in power markets that will constrain prices and price volatility. Second, creditworthiness is improving but still is not robust. Third—and related—liquidity is improving but still not great. In these situations, the fall into the hole occurs with great swiftness, but it takes far longer to crawl out of the holeUrealistically, the process will be a long one," Pirrong said.

In retrospect, he noted, events "took on a life of their own, and a vicious cycle resulted. Merchant energy stocks were overvalued prior to the Enron meltdown. There was something similar to the phenomenon observed in the dot.coms and telecoms. That said, I think there was something more substantial to merchant energy companies. They did—and still do—have an economic function."

Enron's collapse had negative repercussions for the entire merchant energy sector, but Enron alone was not the entire story—at least not directly, he said.

Pirrong attributed a second, broader stage of the merchant energy collapse to legal-regulatory risk developments. This stage coincided with a broad sell-off of merchant energy companies' stocks during April-June 2002.

"At this time, questions about wash trading and false reporting—combined with continued legal and regulatory fallout from California—put the entire sector under siege," he said.

Wash trades, also called round-trip trades, are when a company simultaneously buys and sells electricity or natural gas to the same counter party. Although not explicitly illegal, the practice was used to inflate a company's trading volumes.

In response to allegations from the US Commodity Futures Trading Com-mission, 26 merchant energy companies had paid $252 million total as of July 29 to settle allegations of false price reporting or attempted market manipulation.

Separately, a US Securities and Ex-change Commission announcement that it was investigating Dynegy resulted in the company's stock price plummeting by 50% and eventually falling to less than $1/share during fourth quarter 2002.

"The reduced equity values impaired the creditworthiness of the merchant players. This impaired their ability to trade and reduced market liquidity. Inasmuch as much of the value of these companies was driven by the prospect of trading profits (and not just spec trading, but the ability to create structured products to help their customers manage risk), this reduction in credit, liquidity, and trading ultimately was fatal to the sector's prosperity," Pirrong said.

Debt outlook

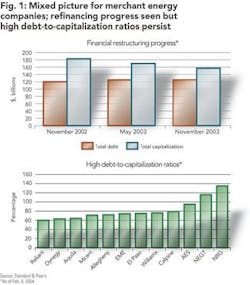

S&P's Rigby predicts that energy merchants will face financial struggles throughout the rest of the decade. Energy merchants face nearly $65 billion in loans due by the end of 2010 out of a total debt burden of $125 billion, Rigby said in a Feb. 9 special report.

"In less than 10 years, US energy merchant companies have gone from the cradle to the graveside, if not the grave itself. In the past 2 years, well over $100 billion of energy merchant market capitalization has disappeared, as almost everything that could have gone wrong with the nascent energy merchant industry did," he said.

S&P credit ratings for 12 companies owning more than a combined 200,000 Mw of power generation capacity worldwide have fallen from investment grade in May 2001 to low noninvestment-grade levels, he said.

"Based on current data, it is unlikely that unsecured lenders to bankrupt energy merchants will see anything near par recoveryU. In short, almost every worst-case scenario that these companies and their lenders considered possible, but remote, has become its base case scenario."

Although most of the 12 companies sold assets, primarily contracted-for power plants and regulated pipelines, "they still carry too much debt to be strong competitors in the volatile energy markets," he said.

Each of the 12 companies pursued the energy business differently, and different lines of businesses make strict comparisons difficult, he noted. Many of the companies refinanced their debt by pushing out maturities for several years.

Rigby warns that those extensions could exacerbate the long-term problem because the obligations still will have to be addressed sooner or later.

"The shared strategy of rapid and debt-funded growth premised on rapid deregulation of the US electricity industry and open competition has not played out," Rigby said. "Deregulation not only did not spread more rapidly and widely as many anticipated, but may have actually contracted in the wake of the California power crisis and, to a lesser extent, the Enron bankruptcy."

The lesson these companies must learn is how to operate "under much more conservatively financed structures than many energy merchants first envisioned," Rigby said.

But attorney Robin J. Miles, a Bracewell & Patterson LLP partner in Houston specializing in energy and finance, believes that S&P is "overly pessimistic. The capital markets and institutional markets are still strong.

I've seen companies recently go back to the capital and institutional marketsUto refinance their restructured debt to extend maturities and to gain more flexibility."

He has represented Reliant Energy Inc. in its debt restructuring and secured bond offering. He also represented, Dynegy in its recent bank refinancing and was counsel for a major financial institution in the debt restructuring of El Paso.

"The merchant energy companies seem to have stabilized," Miles said of the sector. "They will come up with a new business model; they are cutting costs."

Companies' status reports

Dynegy implemented what Chairman, CEO, and Pres. Bruce A. Williamson calls "self-restructuring" by working with bankers and bondholders in order to restructure the company's finances, which have rebounded from fourth quarter 2002, when its stock sold for less than $1/share and bonds traded at about 20¢ on the dollar.

A former Shell Oil Co. assistant treasurer, Williamson was hired as Dynegy president during one of its hardest times. Despite all the poor market indicators upon taking his new post, he rejected the bankruptcy route.

"My view was that Houston had had enough of that with Enron, and we didn't need a second company going down that path with all the uncertainty that it brings.

"The self-restructuring has worked very well. Our stock has rallied to $4/share, and all of our bonds are at parUthe company got itself into this mess, and we are going to get ourselves out," he told OGFJ in early August.

During Williamson's first week on the job, Dynegy discontinued its trading and marketing operations, which previously had been the company's key business.

"We are a gas gatherer and processorU. Our larger business is power generation. We take coal, gas, and oil and convert those to electricity. My view is that we are no different than somebody who makes blue jeans or shoes. We are interested in buying our fuel as cheaply as possible and in making as many electrons as possible."

Williamson said Dynegy's emerging strategy is similar to a refiner's in that it's driven by the price of fuel and by its

profit margins. Dynegy reported a positive net income for the first and second quarters of this year.

In resolving its problems, Dynegy took its debt from $9 billion in 2002 to $7.4 billion as of Dec. 31, 2003.

"At the end of this year, we will be at $5.5 billion, with another $500 million of cash on hand, so net debt should be right at $5 billion at yearend," he said.

Dynegy continues to work on what Williamson calls its "restructuring to-do list." One of the remaining items is a reduction in the debt-to-capitalization ratio, which was 66% in early August.

The pending sale of Illinois Power to Ameren Corp., St. Louis, is expected to trim Dynegy's debt-to-cap ratio to somewhere closer to 55%, a company spokesman said.

Williamson believes the sector's collapse stemmed in part from lack of focus on cost structure—specifically a misdirected notion partially stemming from a regulated mindset in which "50-60% debt-to-cap was considered OK."

He expects to see consolidation within the merchant energy sector, adding that it will yield more cost-effectiveness just as consolidation had done for the oil and gas production and service-supply industries.

"Wall Street is looking at all merchant companies right now and watching management teams to see how disciplined those teams are in leading the companies out of the past. They also are looking at the quality of the underlying assets. Wall Street is watching to see who can make money even in a down market," he said.

Each merchant company has had its own saga in the aftermath of the sector collapse.

El Paso presented a long-term business plan in December 2003, saying it will exit several business lines within 3 years. That will leave the company focused on two primary business activities: natural gas pipelines in the US and Mexico and exploration and production with an emphasis on gas production.

Previously, the company said it was getting out of the trading business. Doug Foshee was named president and CEO in September 2003.

"We believe that investors have been supportive of our plan, and we have made significant progress so far. We have reduced our debt significantly," a company spokeswoman said.

As of late July, El Paso had announced or closed $3.5 billion out of $3.3-3.9 billion in its targeted asset sales by yearend 2005.

The Houston-based company believes that an integrated business model remains workable both for itself and for the energy industry overall.

"Over time, El Paso will review that question and determine if the same set of shareholders should own our pipelines and our production business. We will do whatever is in the best interest of our shareholders," she said.

Sanders Morris Harris analyst John Olson of Houston said El Paso was among "the biggest causalities" of the merchant energy sector collapse.

"The pipelines are not the problem. Production is doubly burdened," he said, referring to reserve shortfalls and hedges that hurt the company's profitability. "It's a double whammy."

El Paso Production Co. reduced its estimated proven oil and natural gas reserves by 1.8 tcfe, or 41%, leaving the company with 2.64 tcfe as of Dec. 31, 2003. Of that total, 66% is proved developed reserves.

Regarding gas hedging, Olson said that, "El Paso had been about the most aggressive. They wrote these hedges with the idea of supplying their own power plants, but that has been wiped out." El Paso is in the process of selling its power plants.

Williams Cos., Tulsa, has implemented numerous efforts to restore investors' faith, including shedding nonessential assets. The company produces, gathers, processes, and transports gas. The company is working to exit or wind down its energy marketing and power activities.

"Williams's overall financial health [and] outlook continues to improve. We see further incremental upside in this name from current trading levels for investors who can tolerate commodity price-related volatility," said Ronald J. Barone, analyst with USB Securities LLC, New York. Second-quarter midstream results were higher than expected, he said.

"Beyond 2004 performance, we are pleased to see management's ongoing focused efforts to pay down debt as rapidly as possible, emphasis on ramping up E&P production as quickly as economically possible, [and] continued streamliningU," Barone said.

Sector outlook

Daniele Seitz, analyst with Maxcor Financial Group Inc. in New York, still sees an integrated business strategy as an advantage for companies in the long run, although she acknowledged that investors and Wall Street remain cautious.

"The convergence idea that was talked about when the merchant business really took off was a positive. Actually, Dominion Resources is trying to implement it in a slightly different manner than originally conceived. Dominion's point of view is that it's an excellent way of controlling your earnings instead of being completely at the mercy of commodity prices," Seitz said.

Navigant's Maschoff also uses Richmond, Va.-based Dominion as an example of an integrated company that has fared well throughout the Enron collapse and energy merchant restructuring.

One of the largest integrated electric and gas companies in the US, Dominion owns and operates more than 24,000 Mw of unregulated generation and 7,900 miles of gas pipelines. It also has oil and gas exploration and production.

Meanwhile, Olson pointed to Oneok Inc., Tulsa, as "the most successful in the survival of the fittest." Oneok is involved in oil and gas production, gas processing, gathering, storage, and distribution. It also has energy marketing and trading operations.

Seitz said an integrated business model can be complicated to explain, especially to investors and analysts who are looking for concise, crisp corporate mission statements.

"But the integrated model makes perfect sense logically, and it makes sense from a point of view that it is helping the company to keep earnings from being very volatile, and it also is helping the company to hedge one business with another business. This keeps the earnings on a more consistent growth basis. It limits the amount of risk for investors," Seitz said.

The perception by the investors can be lukewarm, she said, using Dominion as an example. "If you look at Dominion's E&P division, it's obviously growing by leaps and bounds nowU. But investors are looking at a hybrid company, so it is more difficult for the stock to get value. Actually, the market itself is discounting some value."

In the long run, Seitz believes that convergence is an advantage, but she also acknowledges that the market perception might not yet be on board with the concept.

"The companies in general can see the advantage and are very strong advocates of it, but I don't know that the investor is very enthusiastic about the whole thingU. That is why when you have companies with wide diversity of businesses, it's very difficult to get the valuation total to equal the sum of the parts," she said.