Debate over peak-oil issue boiling over, with major implications for industry, society

Future Energy Supply -1: Oil Depletion

First in a series of six special reports on Future Energy Supply.

Readers are invited to participate in Oil & Gas Journal's online forum on the peak-oil controversy at www.ogjonline.com (General Interest).

The debate over the possibility of a near-term peak in global oil production has boiled over.

The dispute centers on whether the world faces a permanent peak in oil production in the near term and with it a precipitous decline thereafter. Some of the main proponents of this view hold that the peak will come this decade and even speculate that the onset of the peak may already have occurred.

The issue has enormous implications, not just for the oil and gas industry but for all of humanity. Indeed, some proponents of the imminent-peak view offer up apocalyptic visions of a postpeak world—even speculating on the extinction of the human species.

While the debate has been around for decades, there is a new urgency among the imminent-peak theorists. In their view, that urgency is warranted because the day of reckoning is almost at hand, leading to, in the view of a leading proponent, "an historic discontinuity" in the world.

The current dispute has echoes of the "limits to growth" debate of the 1970s, with its emphasis on severe resource conservation and reordering of global priorities away from a strong growth path. As then, questions over a rapidly depleting oil resource are being taken up by social, political, and environmental activists to advance their own agendas. But this time the debate is framed against the backdrop of growing international pressure to adopt measures to combat purported catastrophic climate change. It also comes at a time when heightened concerns about oil supply, geopolitical tensions, and fears of terrorism are intermingled daily.

Because the global economy depends so heavily on access to low-cost oil, the prospect of an imminent peak in oil production suggests oil prices spiking to levels untenable for any economy. While that would strengthen the case for draconian conservation measures and an accelerated shift to other forms of energy, such solutions themselves would cause a massive economic dislocation as well. Governments must start taking such measures now, imminent-peak proponents say, to avert an even worse societal catastrophe.

But those who disagree contend that the statistical models supporting an imminent peak and sharp decline for global oil output—and the reasoning behind them—are flawed and refuted by actual industry performance. The imminent-peak advocates respond that their opponents rely on badly flawed data on reserves and production and place too much emphasis on market forces and technology improvements at the expense of geological science.

The debate—largely between geologists and energy economists—has become increasingly rancorous (see opposing views presented by two leading advocates of their respective stances in articles that begin on p. 38). Bringing the dispute to a head recently was a workshop on oil depletion held by the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas (ASPO) May 26-27 in Paris. (The presentations given at that workshop are are posted at www.peakoil.net.)

Some of the scenarios outlined in the ASPO presentations are grim. And yet other analysts that have taken similar modeling approaches suggest that while there may be cause for eventual concern about peak oil production and decline, the problem could be at least several decades away, not within this decade.

If there is any consensus within the debate, it is twofold: 1.) Oil is a finite resource, and a global production peak and decline will eventually come; the question lies in the timing. 2.) Supplies of low-cost oil are generally declining, which means that the producers with the greatest reserves of low-cost oil will exert even greater dominance over oil markets in the latter years to come.

So for oil and gas companies, the crux of the matter is this: Even as oil price cycle volatility persists in the near term, ultimately a high-oil price regime awaits everyone. Again, the question is: When?

Hubbert's peak

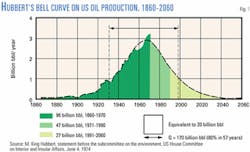

The controversy over oil depletion has its roots in a bell curve developed by a Shell Oil Co. geoscientist, M. King Hubbert, who used it to model annual production and ultimate recovery of oil and gas in the US.

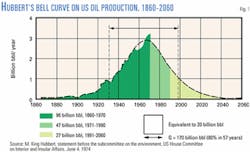

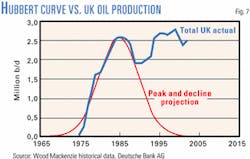

Some say Hubbert's curve was validated when he correctly predicted the peak of US Lower 48 oil production in 1970 (Figs. 1-2). He subsequently attempted the same exercise for Lower 48 natural gas. Since then, however, his detractors contend that he consistently understated resource potential for both oil and gas in the Lower 48 because of methodology flaws (OGJ, Apr. 7, 1997, p. 43; Dec. 28, 1998, p. 33).

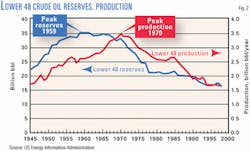

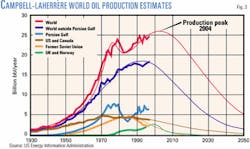

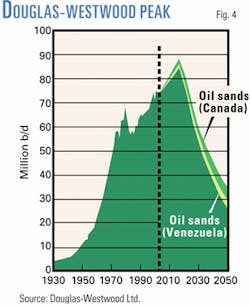

Nevertheless, a number of petroleum scientists have taken up Hubbert's banner and sought to improve on his models and correct errors in his methodology while extrapolating them to the world at large (Fig. 3). And the case for peak oil has gone beyond the province of academics to be taken up by investment banking and commercial consulting groups such as Simmons & Co. International and Douglas-Westwood Ltd. (Fig. 4).

Petroleum science groups such as ASPO, based in Uppsala, Sweden, and the London-based Oil Depletion Analysis Center have emerged in recent years to promote the message of imminent depletion, often in crisis tones, and to share their findings. Even within these groups, there is a range of predictions about the world's ultimately recoverable resources (URR), the date when global production of oil and gas will peak, and the steepness of the decline slope thereafter. But most of the depletionists seem to settle on that peak occurring no later than the turn of this decade, with the subsequent decline slope described as "falling off a cliff." Whether the projection is off by a few years, they nevertheless insist that when the falloff does occur, the downside will be so steep as to create unprecedented energy price spikes.

Hubbert modelers have modified and adapted his bell curve to various regions of the world, such as the North Sea, former Soviet Union, and deepwater areas and found imminent peaks there as well. Some see signs of imminent peak in the current gas supply problems in the US and in the recent downturn in the rate of global additions to oil reserves via discovery—especially when plotted against rising production rates (Fig. 5).

And some of the ASPO presentations took on a political flavor, often with swipes at the US for its aggressive consumption of oil (while already being on the downside of the production curve).

One of the leading peak-oil theorists, Jean Laherrère, retired deputy exploration manager for Total SA, has extended the peak-oil modeling approach to populations and economies, finding more relevance with energy per capita data. Last year, Laherrère's models projected that ultimate oil recovery will total 3 trillion bbl, with the total of all petroleum liquids production peaking at 90 million b/d around 2010.

Imminent-peak detractors

A number of prominent energy consultants, economists, and petroleum scientist have taken issue with the notion that the world awaits an imminent peak in oil production.

Thomas Ahlbrandt, world energy project chief with the US Geological Survey in Denver, objects to the concept underlying the Hubbert curve.

"Is there an imminent oil peak? The short answer is no," he said. "I believe in the plateau concept, which reconciles the need for additional resources within the constraints of infrastructure and capital investment.

"The symmetric rise and fall of oil production is not technically supportable, as Hubbert, Laherrère, and others have published, although generally not recognized by (Colin) Campbell, (Kenneth) Deffeyes, and others who hav been making draconian end-of-civilization claims since 1989 and every year sinceU.Why is there no accountability for these failed forecasts either by Hubbert or disciples such as Campbell, Laherrère, etc.?"

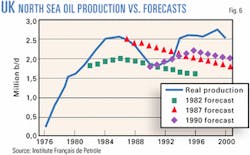

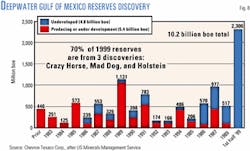

Instead, Ahlbrandt and others point to even mature areas such as the UK North Sea, which in the past 20 years has repeatedly defied forecasts of a bell-curve-style decline (Figs. 6-7). And peak-oil critics also noted the surge in discoveries in areas deemed critical for future supply, such as the deepwater Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 8).

Sarah Emerson, managing director, Energy Security Analysis Inc., Wakefield, Mass., is one of many energy economists who contend that the Hubbert modelers disregard the roles of oil supply, demand, and prices as well political and regulatory impacts.

"I do not believe the peak in global oil production is imminent," she told OGJ. "UThe geologists who present the resource scarcity argument tend to ignore changes in the economic context. For example, foreign investment laws can change in countries with large reserves and limited access to capital or technology. This means places where we never expected development (or expected slow development) suddenly open up. A list of the countries who have opened up to foreign investment is an impressive who's who of producers: Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Venezuela, now Iraq, and maybe even someday Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. New-found access to capital and technology requires a total reappraisal of resource development."

She contends that the global oil industry and market is "incredibly dynamic, constantly changing as it responds to regulation and innovation.

"The Hubbert curve analysis is far too static to stand as a guiding assessment of the future of global oil supply. As with any 'model' results, it should be one input into a broader, more comprehensive market analysis."

Other consultants acknowledge some value in Hubbert-style modeling but arrive at different results.

Fereidun Fesharaki, head of Honolulu-based FACTS Inc., told OGJ that he accepts that the world oil production peak is "imminent," but he expects it to occur "sometime in the next decade, not this decade.

"This pick applies only to conventional oil, and nonconventional oil can delay the peak to the 2020s."

The Centre for Global Energy Studies, London, has "done quite a lot of Hubbert-type work over the years with respect to crude oil," said CGES Deputy Executive Director and Senior Economist Leo Drollas. The CGES models stopped at 1973, however, because "after that date, oil production was not amenable to Hubbert-style analysis due to (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) policies."

CGES's latest modeling effort finds global oil production tracking oil demand growth to 2020 and declining along a moderate slope thereafter.

"Because of shut-in crude oil production (almost all of which is in the Middle East), we think the world's crude oil output can continue to grow at the rate at which oil demand is likely to grow (1% per annum) until at least 2020, peaking at around 81 million b/d (compared with around 68 million b/d in 2003) under the 2 trillion bbl (URR) case.

"Thereafter, conventional crude production will decline gradually, reaching 33 million b/d by 2040, allowing unconventional hydrocarbon liquids to step in. Oil prices need not be sustained at high levels until 2020, but after that date it is more than likely that oil prices will trend upwards."

Edinburgh-based Wood Mackenzie Ltd. noted the slowdown in discovery rates in traditional (including deepwater) exploration areas but instead concluded that, in fact, a near-term production glut looms. WoodMac contends that the top 10 international major oil companies it tracks—with a current strong inventory of development projects and plans for record capital spending—will hike output during 2002-07 by an average 2.5%/year.

"While production from some areas such as the UK and the US Lower 48 are now in decline, this is being more than replaced by increases from deepwater areas in West Africa and the Gulf of Mexico and the continuing development of Caspian reserves," WoodMac consultants Derek Butter and Martin Purvis told OGJ. "Beyond this, we see production from fields in production or which are likely to be developed in the medium term falling, but some of this shortfall will be replaced by new discoveries. If discovery rates in these areas remain at present low levels, this will imply production from these sources peaking somewhere in the 2010 to 2015 range.

"It is, however, possible that exploration efforts lead to the opening up of new provinces, for example the Offshore Arctic or Offshore Northern Siberia, which will delay this."

But the WoodMac consultants also cited surging production in Russia, the ramp-up of nonconventional oil output in Canada and Venezuela, and remaining surplus productive capacity in the Middle East in claiming that they see "no immediate threat to conventional supply."

OPEC's 'hidden reserves'

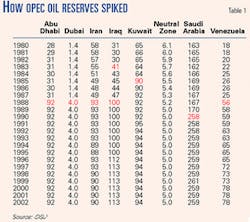

One of the major areas of contention in the peak-oil debate is the lingering question of how much oil remains in the Middle East. Given the opacity of underlying data, the dramatic revisions to reserves among the key Middle East producers in the 1980s stirred up much controversy. Oil & Gas Journal annual production and reserves data have been at the center of the storm (Table 1). Peak-oil defenders denounce the huge jumps in reserves for these countries surveyed by OGJ as "spurious" or "arbitrary" revisions dictated by the need to inflate reserves numbers in order to secure a more-favorable OPEC quota.

"The 300 billion bbl added (in the Middle East) during the second half of 1980s is due to the OPEC decision to decide the quotas from the reserves," Laherrère told OGJ, "so most of the OPEC members increased their reserves by 50% to get higher quotas, when in fact during this period the discovery in the Middle East was less than 10 billion bbl."

Another prominent peak-oil defender, National Iranian Oil Co.'s A.M. Samsam Bakhtiari, questioned the methodology by which reserves in some key Middle East countries are calculated.

"I know from experience how 'reserves' are estimated in major Middle Eastern (and OPEC) countries," he told OGJ. "And the methods used are usually far from scientific, as the basic knowledge for such a complex exercise is not at hand."

Bakhtiari questioned OGJ's proved reserves estimate of 90 billion bbl for Iran, citing instead the estimate of "one of the most prominent experts on Iranian oil reservoirs, Dr. Ali Muhammad Saidi" (retired from NIOC in 1980) of 37 billion bbl.

He also questioned the roughly 90 billion bbl jump recorded for Saudi Arabia "after a rather poor 1980s."

"Either these umpteen barrels had been 'forgotten,' or they were newly 'found,'" Bakhtiari said. "Now, experts at the four US oil companies in (Saudi) Aramco could not have overlooked a couple of Ghawars or so. And there were no major discoveries of supergiant fields in Saudi Arabia during the late 1980s to justify any such addition to reserves.

"On top of that, the Saudi revision came on the heels of similar 'spurious' revisions by other major OPEC members in 1987-88. Hence, it would seem that Saudi Arabia was trying—at a stroke of the pen—to catch up with its main OPEC partners."

Drollas dismisses the depletionists' argument about OPEC reserves as a "red herring" because "the Hubbert methodology does not rely on recoverable reserves as such."

"The Hubbert scheme is based on two key driving forces—the amount of ultimately recoverable oil reserves and the historical record of depletionUThe world's crude oil production history from 1918 to 1973 does not help us distinguish between URRs of 2 and 3 trillion bbl, which is a pity."

Ahlbrandt, citing his experience in the Middle East, acknowledged that "the motives of every country in the Middle East certainly can be questioned, as some have done.

"However, when I look at the data, I see larger, not smaller, resources there than already stated. Most of the world hasn't had to worry about reserve growth much, but it is coming and is adding significant volumes already, as we have documented in a number of international studies."

Fesharaki accepts the claim of "spurious" revisions but with a caveat: "I believe this claim is correct, and I was myself privy to the fact that in most cases no new oil was actually discovered. I also do believe some of these data are exaggerated, and there are increasing decline rates in some countries.

"However, I also do believe there is much undiscovered oil and there is room for increasing recovery rates in a substantial way. So, yes, no real oil was discovered, but we believe it is there, and with new technology and more effort it will be discovered."

WoodMac analysts Butter and Purvis concurred, comparing the consulting group's own database that incorporates "technical" reserve numbers for undeveloped fields along with its proved reserves numbers.

"While in most countries this is usually because the fields are uncommercial, in OPEC nations, it is because the fields are not yet required, due mainly to the quota system. When combined, these figures provide an indication of remaining recoverable reservesU.In our opinion, the remaining reserve potential of the main OPEC member states is not being overestimated."

Reserves growth

The issue of reserves growth in general is controversial, as OGJ found out with its last Worldwide Report, when it reported a 181 billion bbl net increase in global oil reserves (OGJ, Dec. 23, 2002, p. 62).

It was the biggest jump in reserves estimates since the OPEC-inspired increases of the 1980s.

Some readers objected to the inclusion of Canada's oil sands reserves figures in the totals; that step alone boosted Canada's total by 175 billion bbl, a 3,600% increase in a year and a No. 2 slot on the world's list of largest reserve holders.

Conversely, a surprising drop in Mexican reserves in that same report—by 53%, or 14 billion bbl, to 28 billion bbl—stemmed from that country's use of SEC definitions.

On this score as well, there is little common ground for agreement.

Ahlbrandt claimed that technological innovations in the oil and gas industry "are manifested in increased success rates—in spite of less drilling—and the enormous contribution from reserve growth.

"We have documented detailed reserve growth in the world and have published detailed reserve growth studies in the West Siberian basin, the Volga-Urals, Middle East, and, most recently, presented reserve growth studies for the North SeaU.The North Sea example demonstrates the phenomena in a significant, technologically advanced provinceU."

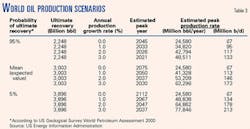

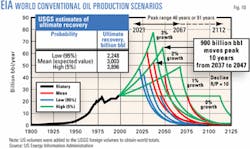

That view resonates in the picture the USGS painted of potential world petroleum resources in 2000 (Table 2). That assessment pegged the amount of future technically recoverable oil outside the US at 2.12 trillion bbl and an ultimate mean global URR of 3 trillion bbl. That compares with some peak-oil advocates' estimates of the entire global conventional oil endowment, including cumulative production to date, at 2 trillion bbl—of which half has been produced.

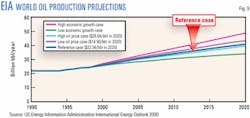

These numbers were the basis for the US Energy Information Administration projecting, using the USGS mean estimate, that world oil production will top 40 billion bbl/year by 2020 (Fig. 9) and peak in 2037, registering an average growth rate of 2%/year. Using the USGS high-case resource estimate of 3.9 trillion bbl URR, that peak is pushed out to 2047 (Table 3, Fig. 10).

Ahlbrandt contends that reserve growth is important because it underpins the plateau concept he cites for future oil production: "UYou add reserves as needed, and the most economically viable resources are those in fields already discovered.

"In a simple analog, you don't carry more inventory than you can sell within your economically viable targets."

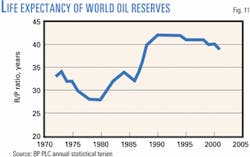

Such a view would track with the recent trend in the world's oil reserves-to-production ratio, which generally has been at a plateau for more than a decade now (Fig. 11).

But some depletionists dismiss R-P ratios as meaningless in the context of ultimate recovery and peak production. Laherrère criticized OGJ for what he claimed was an uneven approach to reporting reserves and production.

"OGJ was right to add the 175 billion bbl of Canada tar sands, if the oil from the tar sands is included in the oil production." (In its annual Worldwide Report, OGJ oil production figures are limited to conventional crude oil and condensate. By contrast, Laherrère noted, BP PLC, in its annual statistical energy review, excludes oil sands from its reserves numbers but not from its production figures. [see story, p. 34])

"But adding the tar sands produced mainly by mining obliges (OGJ) to add also the OrinocoUextra-heavy oil production," which he contends is actually closer to the definition of conventional than is Canadian oil sands mining.

When the point is made that OGJ reports only proved reserves, Laherrère said, "For me, proved reserves does not mean much and has no interest. But it is ridiculous to put 10 significant digits in this totalUwhen the difference with BP is more than 100 billion bbl."

Alhbrandt took issue with that view.

"When I talk to the Malthusians, Hubbertians, pessimists, depletionists, doomsters, or whatever term you like to use for them, they all become very uncomfortable with adding so-called unconventional oil resources to the picture," he said. "They prefer to argueUindividual nations are so absorbed that they would rather destroy the rest of the world rather than develop these unconventional resources.

"You don't get invited to the big shrimp dinners, lecture tours, etc., by pointing out that there really isn't a supply crisis unless you restrict the argument to the cheapest, geographically most preferable regions and exclude all other supplies.

"It is dangerous to run around the world saying we are going end civilization (wars, economies collapse) because we are running out of oil, when clearly we are not.

"World oil reserves (conventional, recoverable), using IHS (Energy) data, increased 15% from 1996 to 2001; they increased 36%, if you use the Oil & Gas Journal reserve numbers.

"If, however, you start excluding offshore oil, as Campbell does, because it is too expensive (although I would think it is up to the companies to determine this), then you can get a crisis of the cheapest oil sources of the past century.

"Most consumers aren't too worried about whether their gas tank was filled by oil from Offshore Nigeria, tar sands of Canada, or from the Denver basin."

Reserves standardization

Complicating the debate is the fact that there is so much disagreement over the definition of reserves, as can be seen in the flap over OPEC reserves.

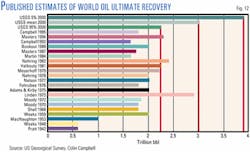

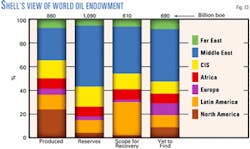

Some of the peak-oil theorists contend that there is little value in the concept of proved reserves in the discussion of when global oil production will top out. That is a major sticking point in the debate. When there is so little agreement on the definition what is "recoverable" and what is a "reserve," it isn't surprising that there is such broad disagreement over the world's ultimate oil recovery (Figs. 12-13).

Ahlbrandt, who is also vice-chairman of the United Nations Committee on Sustainable Energy's Ad Hoc Group of Experts on the Harmonization of Energy Reserves/Resources Terminology, noted that the committee has proposed a classification system based on reserves and resources terminology employed by the Society of Petroleum Engineers, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, and World Petroleum Congresses but applied in a system worldwide to allow understandable terms.

"It is tough sledding," he said of the effort but adds that "it is critical to get a common international harmonization of terminology."

Fesharaki noted improvements in reserves reporting data from China and Russia, and he noted that "standardized reporting is good for everyone—except those who exaggerate their reserves sometimes in the hope of getting higher OPEC quotas.

The whole concept of proved reserves is "obsolete," Laherrère claims, "as the (US Securities and Exchange Commission) refuses the probabilistic approach." He targeted Russia's reported reserves numbers for special criticism as "grossly exaggerated" and in need a of 30% reduction.

"The only good reserve classification is the Norwegian one, but no other country has followed them," Laherrère noted.

Kjell Aleklett, newly elected ASPO president, said he thinks it extremely important that standard definitions be used: "Lax reporting procedures and ambiguous definitions have made it possible for economists to reach fundamentally flawed conclusions that fit economic theory but ignore the rules of nature."

Standardized reserves reporting could help inform the debate on depletion if it were to allow oil companies to provide more information on reserves, said the WoodMac consultants. Too-narrow definitions imposed by the SEC don't accurately reflect companies' resource potential, which is better reflected by 2P (proved plus probable) numbers, they said. Canada has already moved toward this standard, they noted.

"Reporting reserves on an entitlement basis also distorts the reserve base of these companies, as this excludes reserves produced as royalty payments and the host government's share of oil under production-sharing contracts. An increasing proportion of production is produced under these type of contracts due to increases in Africa, Asia, and the Caspian regions," the WoodMac consultants said.

It is in company's interest to book less reserves when submitting to a fiscal regime that extracts its rent from a combination of royalties and shares of profit oil vs. imposing a tax on oil production, they noted.

Accordingly, reporting reserves on a gross working interest basis "would certainly be preferable when trying to assess a company's reserves from the point of view of depletion considerations."

Demand factor

Taking a back seat in much of the debate is the role of global oil demand. Because there are so many variables in projecting future oil demand, it is difficult to assess the role of demand in future oil supply projections. And the depletionist school's emphasis on URR leads them to disdain energy economists' views that oil supply will grow to meet demand as supply constraints yield price incentives.

If anything, the depletionists claim, high prices squelch demand, helping to stave off the day of peak-oil reckoning—but not indefinitely.

"Whatever we can save we can use later, with the important consequence of delaying peak," Aleklett said. "Demand is one of the defining factors. The Club of Rome (the group that produced the "limits to growth" scenarios in the 1970s) made the erroneous assumption that the demand for oil would increase by 4%/year during the 1970s. It means that more is left for us to use now."

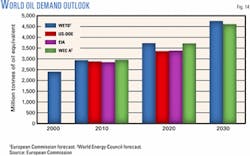

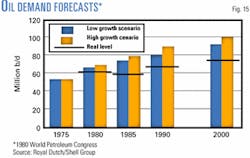

Since then, more recent forecasts, such as those by EIA and the International Energy Agency, peg oil demand growth at 2%/year for the next 20-30 years (Fig. 14). EIA's latest estimate calls for world oil demand to reach 119 million b/d in 2025.

When the depletionist school calls for an oil supply peak at 90 million b/d or less a decade or more sooner, it's easy to see the basis for their concern and apocalyptic scenarios.

But forecasts of world oil demand often overshoot the mark because geopolitical and economic events have a way of disrupting the models (Fig. 15). That's especially true since the energy crisis years of the 1970s largely dispelled the notion that energy demand is inelastic.

Bakhtiari and Laherrère, in fact, see what they refer to as "bumpy plateau" for oil supply, rather than a sharp peak, as a consequence of price and demand signals in the peak-oil transition years.

However, "I don't think that any price rise will come to drastically change that global 'bumpy plateau,' only extending it for a few months," Bakhtiari said.

One peak-oil advocate who requested anonymity contends that oil prices will rise in response to the onset of global production decline, "but they will send a signal that comes too late, given the long lead times to create new energy infrastructures. This will result in a reduction of demand, but, unfortunately, the so-called room of maneuver will be short-lived because the Middle East oil supply will continue to decline, with little chance that new investments will be sufficient to compensate for both this decline and the potential rise of demand."

To this view, Emerson offers a blunt retort: "If we were really running out of oil, the price signals would be there to turn mud into gasoline."

She contends that while the global economy depends on oil, for a number of reasons—environmental controls, taxation, energy security—the years of surging growth in demand may be behind us.

"Even in the US, where gasoline consumption is central to our consumer-driven economy, states are setting targets to rein in demand or increase taxes. The high demand of the 1990s is looking more and more like an anomaly."

It is the US's strong oil demand that brings the country criticism from some of the peak-oil theory advocates.

"I may be asked why the US is using 100% more (energy per capita) than Europe although enjoying a comparable standard of living," Aleklett said. "The US is consuming 25% of the world's energy supply, which many other countries, especially in the developing world, must consider an inequitable distribution, making it a likely cause of conflict and tension. This is underlain by the fact that US (oil) reserves support domestic demand for only 4 years."

But Fesharaki contends that the depletionists underestimate the demand factor.

"A severe price shock can reduce demand substantially and make the reserve last longer. Bottom line is that we are in decline, medium term, (for) supply, and the speed of the decline will depend on the demand factors as well as price. The decline will come but can take between 10 to 30 years, depending on the factors discussed."

Near-term outlook

The world may indeed be getting an early taste of a long-term high-oil-price environment, given that oil prices have hovered near $30/bbl for the better part of a year now. The depletionists welcome that as a means to help stave off what they see as a day of reckoning and applaud OPEC's efforts to sustain oil prices in a band of $22-28/bbl for an OPEC crude basket.

"The only way to solve the problems of energy for the next 30 years is to have high energy prices," Laherrère asserted. "Mankind survived in the past in front of glaciations and other problems as they moved and changed their behavior. Now most of the developed countries do not want to change their way of life. The western way of life was based on cheap energy. We must change it."

Bakhtiari contends that a "linearly planned price increase would be a boon for the oil industry and the world at large. Even for producers, as volatility is detrimental all around. But, unfortunately, linearity doesn't seem possible for oil prices; in fact, only abruptly disruptive cycles occur.

"There are signs that some oil and gas experts have reached the conclusion that if ASPO is right, the question of availability will soon take precedence over price. But the general public is not ready yet, and it won't be ready to accept the new paradigm until it clearly sees the wolf snapping at its heels. Then, and only then, it might accept that this time the wolf really is there."

Emerson noted the effectiveness of OPEC's price defense strategy in recent years.

"If Saudi Arabia wants to support prices, reintegrate Iraq, and mollify Algeria regarding quota, it will have to give a little of (its) market share up...but not a lot. Moreover, it will make strong efforts to share the pain with the rest of OPEC.

"I think OPEC can avoid a significant decline in prices below the $22(/bbl) floor, especially with strong product markets emerging as fuel specs tighten and overcapacity in Asia is whittled away."

While OPEC's current policy might seem to support ASPO's mission, Fesharaki warned that "OPEC decision-making does not take place in an academic, long-term model. OPEC is willing to lose market share in the short term rather than give up revenueU"

While he believes oil prices will come down to the bottom of the OPEC price band or even to $20/bbl or so in the next couple of years, Fesharaki said, "No one wants lower oil prices: not producing governments, not consuming governments, nor existentialists, LNG folks, or alternative energy producers.

"OPEC is not convinced that the depletion is around the corner and will not formulate policy in that framework."

On the other hand, Fesharaki contends that "a severe European-style tax in the US can delay the decline by quite a few years."

CGES and WoodMac, however, see near-term downward pressure on oil prices.

"If anything, oil prices are likely to trend downwards over the next 10 or so years because of the overhang (in Middle East production capacity)," Drollas said. "Expected non-OPEC output increases and planned capacity increases by the OPEC member-countries will see to it that oil prices stay around $18-20/bbl (in nominal terms) until 2012 or thereabouts. Thereafter, prices should begin to trend upwards as the oil overhang begins to peter out."

WoodMac's Butter and Purvis point to growing production outlooks for the majors, the resurgence of oil output in Iraq (3.5 million b/d by 2007) and Russia (11.8 million b/d by 2011), and OPEC's quota squabbles in their projection for downward price pressure this decade.

Accordingly, the WoodMac consultants claim that OPEC will face continuing pressure to scale back production to maintain prices, with the call on OPEC oil not returning to 1998 levels until 2007 or later.

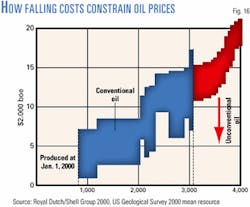

"Beyond this, OPEC is likely to be able to exert more influence in setting prices at its desired level as its influence grows; however, at sustained oil prices above $20/bbl, nonconventional production can compete with OPEC supply (Fig. 16)."

Implications for oil firms

The likelihood is that even if oil prices do moderate in the near term, the result ultimately will be a greater concentration of oil supply in the hands of the countries with the largest oil reserves and a greater reliance on those countries by the net oil importing countries.

So at the least, the longer-term outlook is for higher oil prices and thus improved prospects for oil companies.

"The oil companies will certainly thrive in the postpeak era as prices shoot up. They will deal with lesser volumes, but higher prices will clearly compensate: Nice profits at the horizon for quite some time," Bakhtiari said. "The question will be: What will they do with all that cash flow?"

"Especially the three supermajors (BP, Royal Dutch/Shell Group, and ExxonMobil Corp.) will be in demand, more than ever before, for their experience and management skills, because production will have to be optimized across the globe—as every single barrel will come to pull its full weight.

"Crude supply optimization will have many other consequences, for all players in the Oil Game."

Laherrère, for one, advises oil companies to return to the basics of how to find oil.

"Oil companies need more science and less technologyU.Who knows now how to read an old log? How many new geologists know how to recognize a sediment on an outcrop?"

Yet any future oil boom resulting from price shocks may be mitigated by the growing diversity of the world's energy mix.

The WoodMac consultants noted that the global energy infrastructure has become less dependent on oil since the oil price shocks of the 1970s—since 1973 the amount of oil consumed in the world for each dollar of economic output has almost halved.

"Only in the transport sector is the world still entirely dependent on oil—in all other sectors alternatives are available, generally at competitive prices," they said.

"While a price shock may occur due to geopolitical reasons, the increasing diversity of supply sources helps to modify this risk. Moving towards a "low-energy economy" would also reduce this risk and serve to conserve natural resources—and this could be achieved by a mixture of direct government legislation and taxation measures. However, these measures would not, we believe, be justified purely on depletionist arguments."