Evolving fuel specifications to drive refining spending in 2002

In 2002, two major trends-clean fuels requirements and industry consolidation-will affect the supply and demand of refined products throughout the world.

Refiners in the US face the possible ban of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) from the gasoline pool within the next few years. More-stringent regulations in California will lead to its complete elimination by yearend 2002. This legislation affects refiners in other areas of the world that export gasoline and MTBE to the US.

Lower sulfur levels in gasoline and diesel will also affect refiners´ operational and construction plans in 2002. The reduction of sulfur will influence refiners in the US, Europe, and Asia and refiners that export products to these regions.

Meanwhile, with crude oil prices depressed, refiners are not as compelled to use lower-quality, less-expensive crudes. Many analysts expect crude oil prices to remain steady in the low $20s/bbl for the remainder of 2002.

This all means that refiners will invest less capital in heavy oil upgrading processes such as coking and hydrocracking and concentrate instead on sulfur removal and octane-upgrading processes.

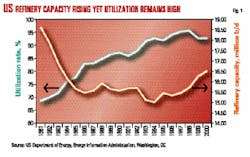

Refiners will also implement revamp projects to increase crude distillation capacity, especially in the US. High capacity-utilization rates, coupled with the possibility of refinery shutdowns, mean that refiners will need extra capacity.

This will be especially true if the demand for transportation fuels recovers to levels seen before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on the US.

Clean fuel specifications

Refiners must deal with three distinct clean-fuels concerns: the reduction and possible ban of MTBE in US reformulated gasoline (RFG) and mandated sulfur reductions in gasoline and diesel fuel.

MTBE

California has specified that RFG must be completely free of MTBE by Dec. 31, 2002. Other states using RFG are also considering partial or complete bans of MTBE.

The removal of MTBE from gasoline has a fourfold effect.

First, MTBE is the easiest way for refiners to meet the 2 wt % oxygen standard required for RFG. The only commercially viable replacement is ethanol, which brings its own set of problems, including fungibility issues. Many refiners are lobbying for a waiver of the oxygen standard.

Second, MTBE is a high-octane blending component. The loss of octane will have to be offset by increased use of alkylate and isomerate. Because the octane ratings of these components are not as high as that of MTBE, even more volume will be needed to make up the difference. OGJ´s Worldwide Construction survey (OGJ, Oct. 29, 2001) identified only 10,000 b/d of new alkylation capacity as coming on line in 2002.

Third, MTBE contributes a significant volume of the RFG barrel; in California it constitutes 12% of RFG. Refiners therefore will need additional crude and reforming capacity to make up the volume difference.

Fourth, the butanes previously used to produce MTBE must either be blended into gasoline or used to produce alkylate. The former option creates a substantial octane loss and a much higher gasoline Reid vapor pressure. Present alkylation capacities limit the latter option.

US refiners will deal with the excess MTBE capacity by exporting to countries needing octane due to gasoline lead phase-outs, simply shutting down the unit, or converting the MTBE unit to an oligomerization, isomerization, or alkylation unit. The OGJ construction survey shows none of these projects currently under way in the US.

Sulfur in gasoline

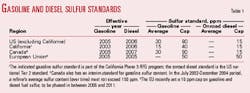

Table 1 lists gasoline and diesel sulfur regulations by region. The US average gasoline sulfur level is 300 ppm, and the average US diesel sulfur level is 350 ppm.

The sulfur standards are technically feasible but will take substantial capital investments to achieve. In fact, some refiners in California are already producing gasoline with less than 20 ppm of sulfur, in compliance with Phase 2 RFG standards.

Because a vast majority of the sulfur in gasoline passes through the FCC unit, strategies to reduce gasoline sulfur focus on FCC feed hydrotreating or FCC naphtha hydrotreating. Most refiners have chosen the latter option because it requires less capital investment and lower operating costs.

In 2001, a number of units treating naphtha to ultralow-sulfur levels came on line. One new technology is Phillips Petroleum Co.´s S Zorb gasoline process. Phillips started up a 6,000 b/d unit in its Borger, Tex., refinery (OGJ, Nov. 19, 2001, p. 72).

The S Zorb process can also be applied to diesel streams.

Sulfur in diesel

Reducing the sulfur in diesel is a greater technical challenge than it is for gasoline. Because the sulfur exists in much larger molecules, deeper desulfurization and, in some cases, hydrocracking are required.

The US Environmental Protection Agency has mandated a 15-ppm sulfur limit for on-road diesel, to be enforced starting in 2006. The European standard is set at 50 ppm with a 2005 deadline, but some refiners there are already producing diesel with significantly lower sulfur levels to take advantage of lower taxes.

For example, a 10-ppm sulfur diesel grade is being marketed in Sweden.

Even more hydrotreating capacity, for both gasoline and diesel, will come on line in 2002. In North America alone, more than 460,000 b/d of hydrotreating capacity is scheduled to come on line, according to the OGJ construction survey. The Middle East is second, with more than 290,000 b/d. Worldwide, almost 900,000 b/d of hydrotreating capacity will be added.

Overall, estimates show that US refiners could spend more than $10 billion to comply with diesel regulations (OGJ, June 25, 2001, p. 56)

Future refining capacity

In 2001, two major mergers involving top refiner-marketers were finalized. Phillips Petroleum Co. acquired Tosco Corp., and the merger of Chevron Corp. and Texaco Inc. was completed.

This trend will continue in 2002, as some further mergers and acquisitions have already been announced.

Valero Energy Corp. will complete its acquisition of Ultramar Diamond Shamrock (UDS) in early 2002, after divesting UDS´s 168,000 b/d Golden Eagle refinery in the San Francisco Bay area.

In early December 2001, Valero Chairman and CEO William Greehey said that he would rather swap the refinery than sell it outright.

Phillips and Conoco agreed to a "merger of equals" in November 2001 and expect to complete the merger in second half 2002.

The combined company may have to divest some downstream assets but will still become one of the top two refiners in the US (competing with ExxonMobil Corp.) and one of the top 10 worldwide.

The more-stringent fuel specifications will take a toll on refining capacity and be especially difficult for small refiners with limited capital. One example is the St. Louis-based Premcor Refining Group Inc.´s Blue Island, Ill., refinery that shut down in January 2001.

Premcor said that, although it had spent $70 million on the refinery over the last 5 years, the plant does not generate a return sufficient to justify the additional investment needed to meet "the next wave of low-sulfur, cleaner-burning fuels" (OGJ, Jan. 29, 2001).

Some small refiners, however, can follow less-stringent sulfur standards for an extra 2 years if they can meet "economic hardship" requirements (OGJ, Nov. 19, 2001, p. 67).

As Fig. 1 shows, US refinery capacity has increased since 1994, but capacity utilization is still near all-time highs.

Any additional loss in capacity, therefore, could lead to regional price spikes in gasoline or diesel fuel as was experienced this past summer in the US Midwest. Additional crude capacity coming on line in 2002, according to the OGJ construction survey, will reach 140,000 b/d.