Egypt cutting arrears to spur natural gas exploration

Anthony Skinner

Verisk Maplecroft

Bath, UK

Egypt remains at the top of the list for international oil companies (IOC), mid-caps, and small exploration and production (E&P) companies considering new concessions. The prospectivity of the offshore Mediterranean has already been proven and Egypt’s Western Desert has a track record of low-cost oil discoveries. While the country’s government continues to cut oil and gas company arrears and increase the efficiency of state-run oil and gas institutions, political continuity is also taking hold.

Eni SPA’s discovery in 2015 of the offshore giant Zohr natural gas field—the largest ever to be made in the Mediterranean—was a game-changer for IOCs and central authorities alike. A joint venture between Italy’s Eni and Egypt’s Tharwa Petroleum plans to begin exploratory drilling in North Sinai’s offshore Noor field imminently, raising hopes that Egypt will have another supergiant gas find.

Even if Noor disappoints, Egypt will remain highly gas prospective, a situation the government is attempting to reinforce by taking a range of measures to boost IOC interest. The government’s efforts are undeniably positive, but problems persist. Chief among these are the outstanding though diminished arrears oil and gas investors still face. Tough fiscal terms and delays in projects due to slow decision-making by middle managers are also problems.

Satiating domestic demand

Despite its estimated 850 billion cu m (bcm) of gas, Zohr will not provide a silver bullet for Egypt’s expanding energy needs over the coming decades. Egypt’s Dolphinus Holdings has inked a $15 billion contract to import Israeli gas over the next 10 years for both domestic use and export, but Egypt does not want to become overly dependent on gas imports. The country is pursuing long-term energy self-sufficiency, with almost 100 million Egyptian consumers adding more than 2 million people to their ranks each year.

Estimates by Wood Mackenzie, our sister company, indicate that annual natural gas demand will grow by a staggering 69% between 2015 and 2020. Demand growth will continue to rise into the next decade, notwithstanding the improbable possibility that the government’s two-child initiative effectively contains population growth. Energy diversification, which includes an ambitious government target to generate 20% of electricity from renewables by 2022, will help address domestic needs but only partially.

These circumstances explain why attracting even more foreign direct investment (FDI) to the oil and gas sector and aggressively driving E&P are top strategic priorities for Egypt’s government. State-owned Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Co. (EGAS) unveiled a licensing round for as many as 16 concessions—13 in the Mediterranean and three in offshore Nile Delta—in May 2018. This accompanied the launch of 11 concessions by the Egyptian General Petroleum Corp. (EGPC), for acreage in the Gulf of Suez, Western Desert, and Eastern Desert.

IOC confidence indicators

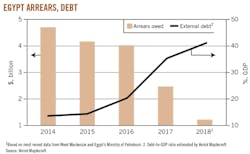

The Egyptian government’s commitment to servicing arrears owed to IOCs reflects its determination to spur E&P activity. As of July 2018, Egypt owed industry investors $1.2 billion, down from almost $4.7 billion in 2014 (see figure). Operators with a large portfolio in Egypt such as BP PLC, Eni, and Apache Corp. tend to be paid more quickly than other companies. Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, Tarek Al-Mulla, however, says that all outstanding debt will be repaid by the end of 2019 as part of International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan commitments.

That is of course if Egypt manages to avoid an external debt crisis, which both Verisk Maplecroft and the IMF believe it will. Egypt’s external debt exceeds 42% of GDP but the Egyptian government has accumulated a strong foreign exchange buffer exceeding $42 billion as of June 2018 and has a flexible exchange rate. Importantly, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s team is effectively pursuing much-needed structural economic reforms and aims to achieve a primary budget surplus of 2% by the end of the current fiscal year, up from 0.2% in fiscal year 2017-18.

Egypt’s biggest macroeconomic problem is external market forces, as starkly defined by much-anticipated US Federal Reserve interest rate hikes later this year. Such forces increase the risk that capital will move away from Egypt, potentially frustrating the government’s ability to roll-over debt on its bonds and treasury bills and by extension souring investor sentiment.

But the Egyptian central bank is pursuing a cautious monetary policy, one in keeping with the IMF reform agenda and designed to avoid scaring sovereign debt investors and IOCs alike. Although Egypt’s sovereign debt will continue to rise over the course of 2019, the government and IMF expect it to come down in subsequent years thanks to ongoing structural economic reforms.

Oil, gas reformation

Egyptian authorities have not only focused their energies on servicing IOC arrears to encourage FDI. Al-Mulla has set an ambitious reform agenda under Egypt’s Oil and Gas Modernization Project. The initiative includes a commitment to reducing the number of bid round cycles and improving efficiency of evaluations.

Oil and gas executives have also complimented the government’s pro-business messaging. Since 2017, a greater number of senior Egyptian officials in the energy sector, including chairmen of joint ventures, have more closely aligned their words and actions with those of Al-Mulla, a former Chevron executive.

A senior manager working for a contractor with a long-standing presence in Egypt told Verisk Maplecroft in April that “the positive, pro-business mind-set has spread at a senior level of government.” He added, however, that “decision-making at the lower levels of EGPC and probably EGAS can still be slow. Individuals are concerned about being held to account for calls which may be scrutinized by an aggressive audit.”

This problem is, however, acknowledged by the Ministry of Petroleum, which in a November 2017 presentation identified complex and slow decision-making and resistance to change as primary difficulties. Reforming its “deeply rooted ways of working” and improving upstream efficiency is a self-assigned objective for the ministry.

Investors are also closely monitoring Egypt’s progress in developing a liberalized domestic gas market. In February 2018, former Prime Minister Sherif Ismail issued an executive regulation to permit private-sector market participation. The reform cleared the way for private firms to import LNG and piped gas while also enabling upstream companies to sell profit-share gas to end-users.

Fiscal-term changes limited

In contrast to the ministry’s desire to improve efficiencies in EGPC and EGAS, its willingness to make large concessions on fiscal terms offered to exploration companies is limited. Egypt’s harsh fiscal terms are defined by low cost-recovery and a high government take. Wood Mackenzie has calculated the average government take at around 80%, well above the global average of 63%.

The Ministry of Petroleum feels that it is fully justified in retaining a large portion of oil and gas-related income, especially with Egypt regarded as the most exciting prospect for gas exploration in North Africa. But potential returns from oil and gas investment can vary significantly, depending on where exploration and production take place. While the odds of good returns in the Western Desert are relatively high, the Gulf of Suez and Red Sea are more of a financial gamble.

Broadly speaking, companies looking for higher returns may opt for concessions in countries that not only have the prerequisite geology but also attractive fiscal terms.

The author

Anthony Skinner ([email protected]) is director for Middle East and North Africa research at risk advisory and analytics company Verisk Maplecroft. He previously worked as a senior editor and consultant in Egypt, Tunisia, Kuwait, and Turkey. Anthony holds an MA (Hons) from the University of Edinburgh and an MSc from the London School of Economics.