Lifting the veil of Norwegian natural gas: One year of 'conventional' gas sales

The rapid implementation of a radically new natural gas transportation regime in Norway reflects a broader revolution getting under way in Europe's gas markets.

Lessons learned in Norway over the past 21/2 years can readily be applied to help shape the emerging new pan-European gas regime that the industry needs.

In May 2001, a "dawn raid" was conducted on the Norwegian oil and gas companies Statoil ASA and Norsk Hydro AS. In November of that year, the European Commission initiated proceedings1 against the GFU (Gas Negotiation Committee), "a Norwegian entity that negotiated natural gas sales and set prices, volumes, and other trading terms on behalf of 30 gas producers." On Aug. 8, 2002, the commission decided to accept2 the commitments offered by "certain Norwegian gas producers"3 (and indirectly other commitments by Norwegian authorities) to:

- Discontinue all joint marketing activities and sales activities, unless compatible with European law.

- Reserve certain gas volumes for new customers who in the past have not bought gas from the Norwegian gas suppliers.4

Certainly this was a shock to the industry, but at the same time it seemed as if the EC decision cleared the air for something that had been coming for a very long time (see box, p. 19).

The companies have bitten the bullet and simply said, "Okay, will do." Phenomenally, a new transportation ownership and transportation regime, along with associated dispatching solutions, were all in place at yearend 2002—the dispatching systems even were in place at the beginning of the gas year, on Oct. 1, 2002. In parallel, a splitting of joint gas sales contracts took place, which involved complex negotiations with buyers, many of whom saw the new contracts as commercially inferior to previous arrangements.

The changes in Norway are now part of a broad and radical new European way of doing business and thinking strategy.5 In the past 2 years, various initiatives have been made and changes made, but typically addressing only matters within each of the European Union and European Economic Area countries. Fundamentally, however, the issues have a pan-European scope, and the road ahead barely has been surveyed. The "systems think" needed for the design of the new European gas business model is extremely fragmentary and still immature.

Norway successfully liberalized its electricity markets overnight with the sweeping 1990 Energy Act, and the Norwegian solutions and ideas were gradually adopted in the Nordel6 countries Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, as well as providing inspiration to Europe generally.

A similar development now has started in natural gas. The changes that will be necessary are likely to be strongly rooted in the past 40 years of European natural gas history.

Strategy for small players

Oil is a complex international commodity handled by big international companies. Gas is largely a regional and smaller-scale commodity, but with a history of statutory monopolies or "privileges." The Norwegian arguments were simple from the start: Buyer power must be matched by seller power. Behind closed doors, the case often was made that the international oil and gas companies could not be trusted to protect Norwegian interests.7

The government's involvement in oil and gas was significant from the beginning (see box, p. 22).

Principles such as national sovereignty of natural resources, a depletion policy based on maximum extraction of reserves, and a Norwegian-led development formed the political and commercial agenda. The international oil companies definitely felt the culture clash. A "Nor-way" was developed that also was cemented in legislation, technical standards, and solutions, as well as commercial arrangements.

In this setting, the parliament was in effect the "board room," and the national oil company Statoil8 was the commercial tool and policy executive. Statoil became synonymous with Norwegian oil and gas, and effectively was also appointed the royal seller of Norwegian gas.

GFU and the Trolls

To Statoil's chagrin, Shell discovered Troll in 1979, a gigantic nonassociated 50 tcf gas field—a dream field both for the geologist and the gas seller. While Shell would develop Troll gas, Statoil was appointed by the government to commercialize and operate the field. It soon turned out that Troll would dramatically influence commercial gas strategy, European energy, and even cold-war politics.9

Statoil was politically downsized in 1984 after a series of events where Statoil appeared also to be running the political show. At the same time, the publicly listed but Norwegian companies Norsk Hydro and Saga Petroleum AS were given new responsibilities in the gas sales processes, which roughly coincided with the start of negotiations for the sale of gas from Troll.

In 1987—"on request from the authorities"—the sales cooperation was formalized by an agreement between the three companies to establish the GFU, but still headed by Statoil. The regime was formalized largely since Statoil was perceived to be too dominant in the seller group.

The major long-term Troll sales contracts were signed in the GFU golden period of 1986-92. Statoil, of course, found it a nuisance to have to deal with Norsk Hydro and Saga, and it took a couple of years for the new system to settle. By 1989, the GFU was fairly well harmonized and largely presented a single face to the outside.10 Several new Troll-based contracts had been signed or were in the works.

In 1988, BASF AG, the giant German chemicals company, found that its gas costs were too high for profitable operations at its main operations at Wilhelmshaven, Germany, near Frankfurt. BASF first negotiated unsuccessfully with Ruhrgas AG for cheaper gas, alternatively "commercial" access to its pipelines. BASF then decided to establish Wingas for the purpose of building its own pipeline system and to secure gas directly from producers.

GFU and the Norwegian gas companies were given an opportunity to be major part-owners of Wingas, provided they would sell gas to Wingas. At yearend 1989, GFU declined to negotiate and sell gas to Wingas, as Wingas stated at rostrums across Europe at every opportunity. Later, Statoil and Norsk Hydro instead became part owners of the Ruhrgas NETRA pipeline.

Wingas eventually got its gas from Russia's OAO Gazprom and has built a major pipeline system spanning all of Germany. Having been snubbed by GFU left deep marks in Wingas and BASF, and the case found its way to Brussels. At the time, the European Commission lacked a legal mandate for proceeding, but the case formed an important backdrop and driver for the drafting of directives to liberalize the EU natural gas market.

Fighting change

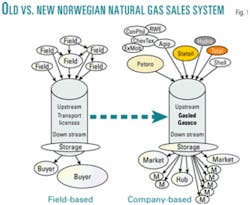

After the passage of the 1998 EU directive on completion of the internal market for natural gas, the pressure on the Norwegian sales system intensified. From the EC's point of view, there was also an issue about the exploration and production licensing system on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, which it considered not to be "open, transparent, and fair." On its side, Norwegian authorities justified its system on the grounds of safety and efficient resource management (Fig. 1).

Norway was square-headed about the long-established system that gave the Ministry for Oil and Energy a tremendous amount of discretion and power. Norwegians feared that market liberalization automatically would lead to a permanent price drop, to coal-equivalence levels, disappearance of take-or-pay clauses, and a collapse of revenues. This was at least the perspective in 1999, when oil prices were threatening to hit $10/bbl.

On its side, the EC had a problem of finding effective arguments, since Norway was clearly an E&P success story, and Norway's ownership of its natural resources was undisputed.

The early commission argumentation and frame of reference was based on US and UK experience, not adjusted for the realities on the NCS. The commission and Norwegian authorities were arguing across a philosophical Grand Canyon.

The case against the GFU companies threw another ball in the Norwegian authorities' court, since they had "requested" that Statoil and Norsk Hydro11 form the GFU. Neither Statoil nor Norsk Hydro felt like paying 10% of their global revenues as a fine for possibly having violated EU competition rules at Norwegian authorities' instruction. As publicly listed companies, this would not exactly boost the share price, either. It was inconceivable that the two companies, which had public ownership shares of 80% and 40%, respectively, would sue their majority owner.

Up to the last, the Norwegian companies publicly defended and openly rallied to the support of the GFU and Norwegian position.12 Norsk Hydro was maybe the most aggressive defender and probably stood to lose the most, at least in terms of prestige.

The case also was made that as long as the downstream structure is still monopolistic, Norway should not change its stance. After 1998, the EU commission's new powers enabled it to finally move on a broad front. The GFU was formally abolished13 on Jan. 1, 2002.

New institutions and systems

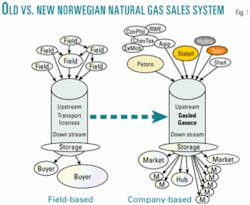

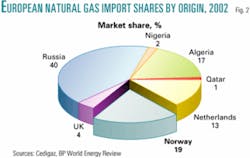

Norway now exports about 3 tcf/year of gas. Out of the current 15 tcf/year demand in Western Europe, this gives Norway a 20%14 market share, with a very large market position in the new and key trading hubs at Bunde in northern Germany and at Zeebrugge, Belgium.

Major new interconnected pipeline systems have been constructed: Europipe, Zeepipe, and Franpipe, as well as the Haltenpipe gathering system, linking mid-Norway fields to the North Sea infrastructure (Fig. 2).

Gassco is now the transmission system operator on the NCS,15 Petoro is the government's "holding company" for direct state engagement16 in oil and gas, and gas producers have direct daily commercial relationship with buyers. On Oct. 1, 2002, the new-era gas year started its unbundled life without a hitch. In a massive effort over 12 months, Statoil and ConocoPhillips had adjusted their legacy dispatching systems; Norsk Hydro, Shell, and Total adopted the expanded HGA (Heimdal Gas Administration) system, while other companies chose to outsource dispatching services from UK-based Gas Management Services Ltd.17 Message formats and content were changed as late as September of that year. Amazingly, the system worked without having gone through a formal testing and validation period—there was simply no time.

The next step in the process took place on Jan. 1, 2003, when Gassco opened its online GasViaGasled capacity booking system. Without much ado, the entry-exit model had been chosen. In the course of 2003 the system was gradually expanded to provide both primary capacity reservation and a system for a secondary "retrading" market for capacity. The entire shipper code and transportation regime was put in place in a matter of months in an intense set of meetings involving Gassco, the producers, and the ministry.

Rather amazingly, there has been absolutely no discussion about copying or adopting existing US or UK systems or network codes, or even the award-winning 3-year-old UK-European Continent Interconnector ISIS (Interconnector Shipper Information System). The philosophy pretty much has been to get it working 80%, with no bells and whistles, and then get to how the system really should look when there is more time.

After just 1 year of "producer-based gas sales" in Norway, Gassco and shippers are now broadly reviewing their experiences and future directions. Gassco already has embarked on the so-called Origo project to replace all transactional systems into an integrated data model and tightly cooperating components by 2004-05.18

Statoil, who before was the leading "shippers' representative,"19 wishes to develop modern solutions to both trading systems and to its 10-year-old legacy dispatching systems.

Companies such as Norsk Hydro, Total, and Shell find that the temporary HGA solution, combined with a plethora of spreadsheets, just won't cut it in a pan-European energy setting. Current physical systems miss a key thing such as integrated capacity management and optimization, with virtually no linkage to trading systems (Fig. 3).

The picture is pretty much the same everywhere in Western Europe, with the perspective of a full market opening in 2006. Last year, it became a corporate "must" to create gas hubs20 in the image of Henry Hub, La., the UK's National Balancing Point, and Zeebrugge.

Currently, second-tier hubs such as Gaselys, EuroHub, NWE HubCo, and Gas Hub Baumgarten play important roles as organized title transfer points with some associated services but are not yet trading hubs in the traditional sense.

Wanted: Pan-European standards

One of the key arguments against liberalization in natural gas and electricity has been based on conflicting and incompatible standards and processes in every member country, some larger than in others. In the initial rounds, the EC did not pay much attention to such arguments, but one of the benefits of the extended time it has taken to decide on the course of liberalization has in fact been a recognition of the importance of these factors.

Initially, most of the discussion around open access related to point-to-point transportation access driven by large end-users. These were not concerned by nor understood the technicalities of bringing physical gas from one grid to another, daily dispatching and balancing with constantly changing demand, and an occasional system or field failure.

With the experience from countries such as the US and UK as well as Norway, initiatives have been taken to stimulate the harmonization of technical standards in gas across Europe. As part of this, EASEE21 gas was established by the EU-sponsored Madrid Club in 2001 (Fig. 4).

As early as 1994, several European gas companies sought to create electronic equivalents to telefax and telex-based commercial communications. EDIG@S was established to maintain and promote the EDIFACT-based initial set of messages that had been developed under the United Nations Directories for Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce, and Transport. Its closest US analogy would be the GISB/NAESB (Gas Industry Standards Board/North American Energy Standards Board Electronic Delivery Mechanism). Currently, there are some 40 standard messages defined in EDIG@S (as of version 2.1). Several gas companies have not implemented an EDIG@S-based messaging system at all, either because of a limited transaction volume, lack of standardized software, high technical threshold, and, of course, cost.

Much of the standardization drive now appears to be in a state of committee limbo, awaiting some kind of resolution of standards. As it is, Europe is very much nonstandard, and only the development of new business processes, trading, and the push from implementing efficient and optimized new business systems is likely to break the current slow progress.

There is hope. There is already a much higher volume of transactions coming from the increased number of users or counterparties—in particular through capacity trading. Belgian Fluxys, which has met the need for a simple system due to the Interconnector, is dedicated to pushing standardization. European gas companies generally soon will have to push towards a tighter electronic-business-based communications model, just like what is now happening in Norway.

The new "hubs" were created with little regard for standardization of the underlying solutions. However, since they are based on a completely new information technology infrastructure (although still only form-based, secure hypertext markup language), they are likely to be important elements in the new emerging e-business messaging infrastructure.

The mental model of a pan-European market for natural gas (and electricity) has taken root quickly in oil and gas companies. Earlier, the corporate model was largely one of a holding company on top of national subsidiaries with fairly loose coordination. Most of these companies now appear to define future success by their ability to "play Europe" in an integrated fashion. In a sense it is the Enron Corp. approach reborn.

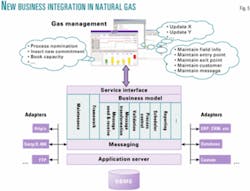

This business idea is easy to draw on paper and very difficult to realize. Getting there requires not only major commercial and organizational restructuring but also the development of integrated systems for trading and risk management and systems to handle the physical execution. Systems for financial and physical management must work together, but, paradoxically, the financial systems appear to be better-developed than the physical ones. Without the physical systems in place, there really is nothing for the financial systems to work with (Fig. 5).

Until now, there have been six groups of systems with limited overlap: production planning, capacity administration, dispatching, physical trading, financial trading, and risk management. When one combines natural gas, electricity, and oil, it becomes a massive challenge. The leading European players are fundamentally technocratic, and post-Enron most of them are working on new and stricter risk management systems. Auditors are forcing this attention, but it may be the wrong business focus right now.

There is a logical sequence, and we believe that the pioneering new gas IT infrastructure projects now under way in Norway are good examples of what will also emerge in Europe in the next 2-3 years.

Some observations about the current status of the road to a pan-European gas industry include the following:

- Transactional requirements in a multistage environment are not yet clear; pipeline and storage capacity, and trading products and regimes are very heterogeneous and immature, making it virtually impossible to be pan-European.

- We are far from a European messaging standard in natural gas; EDIG@S may be only a short-term solution; for the time being, companies will need to handle multiple "protocols" and message standards, even the purely manual, fax, and X.400/SMTP with legacy fixed-format telex.

- The business models are likely to be modified significantly in the years ahead; a need for flexibility is paramount.

- Trading and financial risk management systems are already highly developed—not quite standardized but still bordering on being "shelf-ware"; gas companies instead should give more priority to getting efficient physical systems in place and let trading and trading systems be phased in naturally.

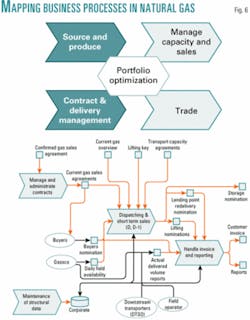

We are presently working with oil and gas companies in designing business processes in natural gas and developing the systems that support them. The separation between systems oriented to the management of physical gas and capacity on one side, and the trading and financial risk management on the other, is very natural. Importantly, it is also a very natural division in terms of the sequence of steps in the change management process (Fig. 6).

Because of the new environment, the common mind set, business understanding and culture of the gas companies have been hit heavily. We have found that a formal mapping of business processes gives a good basis for re-establishing a common terminology and vision of the future, but also for designing and deciding on new business-supporting systems.

Western gas market parallels

The US started its natural gas market liberalization in the early 1980s and spearheaded the development of sophisticated tradable physical and financial energy products, supporting industry messaging and communication standards and systems, as well as risk management concepts. The UK followed a similar process in the early 1990s, borrowing heavily from the US.22

When Norway "kneeled" to the EC in 2001, Enron and other key US energy companies active in Europe were returning home, heavily overextended. Several US and UK companies believed that their early domestic experience with new markets would give them a competitive advantage on the European continent. In reality, the financial engineering was powerful, but they lacked the substance that physical assets give. What is left is a much less exciting Energy Europe, but a market with perhaps a better long-term perspective.

By now the US has solved many of the fundamental issues that Europe still struggles with, also due to the advantage of having had interstate gas commerce and interstate gas transmission companies for decades. There still is no North American standard, which the discussions around ebXML indicate. Similarly, the UK has resolved many issues, but from the perspective of a single insular and harmonized system. The insular nature of gas grids in Europe and the total weight of the established systems make it unrealistic to expect US and UK solutions to be readily adopted throughout Europe.

Instead, Europe is likely to move through the same phases that the US did, but probably a little faster, also helped by new technology. The major "second-mover advantage" is that, it is hoped, many of the problems and unsuccessful experiments can be avoided. As a frame of reference and perhaps a thought leader, the US will remain important, and in a few years and in a more mature, liberalized European market, perhaps US companies will reenter European energy shores again.

The role of Norway and Norwegian producers will be important, partly because of the many gas business linkages across Europe, but also because of its technological orientation. It has always taken two to tango, and an intensified cooperation and standardization among gas companies throughout Europe is the only way forward.

References

1. The commission sent a "statement of objections" (ref. IP/01/830) to Statoil and Hydro on June 13, 2001, as a formal notification of its views on the GFU system.

2. Originally communicated by the commission in an announcement on July 17, 2002 (ref. IP/02/1084).

3. As regards the other Norwegian companies concerned by the GFU case, the commission received commitments from six groups of Norwegian gas companies, which were sellers of Norwegian gas negotiated under the GFU scheme, namely, ExxonMobil Corp., Royal Dutch/Shell Group, TotalFinaElf SA, Conoco Inc., Fortum Oy, and Agip SPA. For these companies, the settlement consists of written commitments to discontinue all joint marketing and sales activities similar to those given by Statoil and Norsk Hydro.

4. Statoil (including the SDØE, the state's direct financial involvement) committed 13 billion cu m and Hydro 2.2 billion cu m for sale in the period to September 2005.

5. Not only is the coming split of Gasunie into Shell and ExxonMobil parts monumental in terms of volume, the commercial strategies chosen by Shell and ExxonMobil also will be determinative for future industry trends. The scale and implementation of the expected new Shell and ExxonMobil gas operations is itself of tremendous interest to EU competition authorities.

6. The association of synchronous grids in the Nordic countries.

7. The distrust of foreign oil companies escalated after the collapse of the 1984 Sleipner gas sales agreement with British Gas PLC. It was argued that some of these companies looked more to their UK and downstream interests than to their Norwegian positions. The companies fundamentally "most distrusted" seemed to have been BP PLC, Exxon Corp. unit Esso, Shell, and Conoco. Total SA and Elf SA had long appeared to be genuinely concerned about good-citizen status in Norway. Shell, while often seen as a "troublemaker" still is accepted, probably because of its exploration success and in being seen as a company that plays "clean." BP appears to have benefited in Norway's licensing rounds from its (odd) international cooperation with Statoil. Both Conoco and Esso have played their American-ness well.

8. Den norske stats oljeselskap, Statoil, was established in 1973 and would be the state's commercial instrument in matters related to oil and gas exploration, production, refining, and marketing.

9. Troll powerfully set Norway on the political scene when the "evil empire" cold-war rhetoric between the US and Russia was at its peak. After the initial Troll contracts were signed in May 1986, then US Sec. of State Alexander Haig, quoted in an article in the New York Times, took full credit for helping Europe avoid energy dependency on Russia.

10. Arve Johnsen was replaced by Harald Norvik as Statoil CEO in 1988, following turbulence related to cost overruns for the expansion of the Mongstad refinery. Harald Norvik's entrance also started the period of a "gentler," more international and open Statoil.

11. Saga Petroleum was acquired by Norsk Hydro in 1999.

12. After 1998, foreign companies were selectively "permitted" into sales processes where their gas was involved, but this was hardly more than a cosmetic exercise.

13. GFU was abolished by the approval of the ministry's proposition to the parliament:"St.prp. nr. 1 (2001-02)."

14. In year 1752, the bishop of Bergen, Erik Pontoppidan, in his book on the natural history of Norway wrote about the "Upeculiar property of the North SeaUthat in places has rivers of oil or streamsUof bituminous and oil-like juices." In 1958, the Institute of Norwegian Geological Explorations stated categorically that "there is no likelihood of finding oil or gas in the North Sea." That picture was shattered in 1959 when the giant Groningen field was found in the Netherlands, ushering in a new view of the world, or in geologists' parlance, a new "geological model."

15. The producers own the pipeline system though a vehicle named Gasled in rough proportion to their production levels and historical investments. This also roughly formed the basis of their initial capacity entitlements, calculated via the ATU (ability to use) concept.

16. Formally the owner of the previous SDØE, which was established in 1984 when the power of Statoil was politically and commercially reduced.

17. Of the 20 or so producers on the NCS, 5 companies run dispatching organizations in Norway, 2 are outside of Norway, and the rest have outsourced the service. Except for Petoro, which has an agreement with Statoil, it appears that companies with annual gas sales over 100 bcf have decided to handle their own dispatching.

18. Transco started its "Gemini" project about 1 year ago, well after Gassco, and still has not concluded its design phase.

19. Since Statoil was established after Ekofisk and Frigg were found, Phillips Petroleum Co. and Elf maintained a dispatching and commercial role on behalf of the nonoperating sellers.

20. Several of the key players may, in the spirit of past power, possibly believe that they can "control" the new marketplaces and forget that trading is a voluntary thing. At this time, only the NPB in the UK and Zeebrugge, Belgium, can claim to be reference-quality, reasonably liquid marketplaces for gas.

21. European Association for the Standardization of Energy Exchange.

22. This also applied to the initial versions of the UK-Link capacity booking and gas administration system that used a number of modules adapted from the Panhandle Eastern Pipeline bulletin board system. Because of the language and culture, several US energy companies, commodity traders, and financial institutions also found it interesting to establish gas-related activities in the UK.

Europe's gas regime antecedents

In 1985, the European Union's "Cecchini white paper" described advantages of realizing an "internal market" and gave 300 steps to remove barriers to trade, which included various measures related to natural gas. The Single European Act followed in the same year and confirmed a radically revitalized EU.

The landmark 1998 EU directive "Internal market for energy: Common rules for the internal market in natural gas" gave the European Commission its long-desired legal authority and mandate. Effectively the directive matches US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Order 436 in 1985, and the 1986 and 1995 UK Gas Acts.

Norway is an associate member of the EU via the European Economic Area treaty and can—at least formally—reserve itself against various directives.

Europe's natural gas industry evolution

After the initial large onshore discoveries of natural gas in Europe during the 1950s and 1960s, gas demand surged, gradually replacing much oil and coal. In particular, Dutch gas drove forward the pan-European gas regime development with long-term export contracts with West Germany, Italy, and France, totaling about 1 tcf/year.

Norway seriously came into focus of the world oil and gas industry on Dec. 24, 1969, when Phillips Petroleum Co. announced the discovery of giant Ekofisk field in the southern North Sea. In 1971, Elf Aquitaine SA found Frigg, a 15 tcf nonassociated gas field in the northern North Sea.

The first decade-long wave of expansion driven by Dutch and local gas was followed by a second wave in the early 1970s, largely involving Algerian and Norwegian gas. By 1977, 36-in. and 32-in. gas pipelines to Emden in Germany and St. Fergus in the UK, respectively, were in place, and several LNG regasification terminals for Algerian gas had been constructed. The third gas contracting wave started around 1976-77 and resulted in with large, new long-term contracts with Russia, the Netherlands, and Norway—in all representing volumes totaling about 2 tcf/year.

Following a boom of exploration activity on the Norwegian continental shelf after the 1973-74 oil price shock, paralleling that on the UK continental Shelf, northern North Sea fields such as Statfjord, Gullfaks, Sleipner, and Heimdal were discovered. These fields provided the basis for the infamous 1979 Statfjord contracts. These high-priced contracts, with heavy take-or-pay provisions, underpinned the construction of Statpipe, which was commissioned in 1984.

The author

Kjell Eikland heads the energy practice of Ementor ASA, a Nordic management consultancy and IT services company headquartered in Oslo. He has more than 20 years' experience in the natural gas industry in the US and Europe and previously has been with Jensen Associates, McKinsey & Co., and Norsk Hydro.