Violence, Crime Continue To Cast Shadow Over Future Oil Investment In Colombia

The then-president of Colombian state oil company Ecopetrol, Carlos Rodado, estimated in July 1999 that his country needs about $6 billion in foreign oil investment by 2010. Rodado was on an international tour to promote improved contractual terms for foreign oil companies. The tour coincided neatly with the scheduled start of formal peace talks with the country's largest leftist guerrilla group-the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Unfortunately, the peace talks were postponed. Once again, conflict-related violence and the uncertainty that surrounds the government's peace initiative cast a shadow over the prospect of future foreign oil investment in Colombia.

The notoriously difficult security environment and the problems it can create for foreign oil companies are among the reasons why the oil boom of the 1980s and 1990s has not been sustained. Large operators such as BP Amoco PLC have scaled back earlier investment plans, arguing that security concerns make them unviable. Some oil companies have left the country. Others are reluctant to enter the fray.

Colombia now faces the prospect of becoming a net oil importer for the first time since 1985, shortly before Occidental Petroleum Corp's large Cravo Norte (Cano Limón) fields came on stream. Significantly, Occidental and BP Amoco between them account 90% of Colombia's foreign-operated oil production. The response of foreign oil companies to Ecopetrol's new terms will test the extent to which the attraction of lower royalties, a reduced state share, and improved contractual terms outweigh adverse security conditions.

Those security issues include exposure to leftist guerrilla attacks and extortion, controversial but necessary relationships with the state security forces, and daily headaches caused by common crime in Bogotá. There is little indication that these risks-and the cost of mitigating them-will diminish in the near future.

Talk and bullets

Peace talks with the 15,000-strong FARC resumed in October, and peace talks with the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN) could progress in 2000. This will have little short-term impact for foreign oil companies.

Both groups have made clear that any talks will proceed without a ceasefire. Kidnapping, they say, will continue until "alternative" financing is provided for the rebel groups. The ELN has even suggested that payment to it of the money spent by foreign oil companies on security might, however, persuade the group to end abductions.

Oil companies will remain prime targets of rebel wrath because of their high-profile presence in remote rural areas and the size of their investments. They are an easy target. Allegations of multinational oil company greed are a convenient ideological banner and rallying cry for the guerrillas to drum up the support of local populations. The ELN quickly denounced Ecopetrol's new E&P terms as a sell-out to the multinationals, adding that it will intensify its sabotage campaign.

In 1999, the ELN fulfilled its pledge to intensify its attacks against oil infrastructure. By late November, it (and the FARC) had bombed the vulnerable overground Caño Limón-Coveñas oil pipeline 64 times, setting the rebels on course to break a record of 77 attacks in 1998. The attacks caused frequent stoppages of pumping operations from Occidental's Cravo Norte field and considerable environmental damage from oil spills. Occidental reported a significant drop in production in 1998 because of the rebel pipeline attacks.

Rebel bomb attacks can go horribly wrong. An ELN bombing of the Ocensa pipeline in late 1998 sparked off a fireball explosion that killed about 70 people in a nearby village. Yet the public outrage that ensued has not deterred the ELN from its campaign.

Over the years, oil company operations and rebel activity have become inextricably intertwined. It was ELN extortion carried out in the early 1980s during construction of the Caño Limón-Coveñas pipeline that facilitated the revival of the then almost-defeated group. Since then, funds extracted from oil-producing areas have been a key part of ELN revenues.

It will be difficult to wean the guerrillas of the high revenues they earn from criminal activities. A recent Colombian army report estimated that the FARC and ELN earned at least $5.3 billion in 1991-98 from drug-trafficking ($2.3 billion), extortion ($1.8 billion), and kidnapping ($1.2 billion).

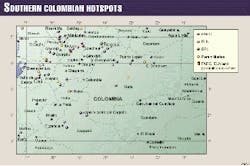

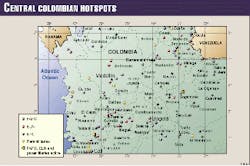

FARC also has stepped up its attacks against state and private oil infrastructure, especially in southern Colombia (Fig. 2). In March 1999, it intercepted and burned 18 tractor-trailers being used by Ecopetrol to transport drilling equipment; attacks against the Trasandino pipeline have become increasingly frequent. In August 1999, FARC bombed a 38,000 b/d oil pipeline in eastern Colombia that pumps crude from 14 small oil fields operated by Bahamas-based Perenco Colombia. FARC targeted one of BP Amoco's Cusiana-Cupiagua drilling rigs in August in another bomb attack.

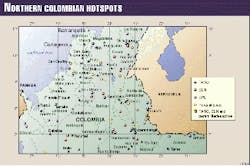

Recent reports suggest that the FARC in fact has overtaken the ELN in attacks on the oil sector. In the past 2 years, FARC has strengthened its presence in the oil-rich ABC area of eastern Colombia-Arauca, Boyaca and Casanare (Fig. 3)-with the express intention of escalating its anti-oil offensive.

"The FARC's Central Command has declared the oil pipeline (Caño Limón-Coveñas) a military objective as well as all foreign companies that exploit our natural resources," a statement from the FARC's 10th Front in Arauca announced as that group's attacks began to gather momentum in mid-1997.

The Army Hydrocarbons Office reports that FARC was responsible for 114 of the total 169 pipeline bombings in 1998, and for 55 of the 93 that took place in the first 9 months of 1999. The FARC's ascendance is compounded by the fact that their bombs tend to be bigger and, unlike the ELN, they remain in the area to ambush the soldiers sent to protect the repair crews.

Ideological goals

There is little indication that the guerrillas will let foreign oil companies slip from their sights. Both the ELN and FARC have made peace talks conditional on a revision of current oil policy. It is highly unlikely that any Colombian government would allow the guerrilla's nationalist, leftist ideology to influence oil policy, and government officials have said as much. Nonetheless, that the role of foreign oil companies should be open to debate in itself is a matter of concern. Oil policy potentially could become a sticking point in peace negotiations.

The ELN is categoric in its opposition to foreign investment in so-called strategic industries. In November 1999, for example, it issued the following communiqué in response to government plans to privatize two electricity companies: "If Isa and Isagen (the electricity companies) are transferred to private ownership, they will be declared permanent objectives of our legitimate sabotage." Foreign oil companies already enjoy this dubious privilege.

If foreign oil companies already are unwilling (and sometimes unwitting) actors in the civil conflict, they now run the risk of entering the agenda for the incipient peace talks.

Paramilitary complications

The FARC justify their attacks against the oil sector as retribution for alleged foreign oil company collaboration with their right-wing paramilitary foes. The oil companies' de facto involvement is undisputable, the rebels say, because of alleged links between the Colombian military that protect oil installations and the paramilitaries.

The controversial issue already has created serious reputational problems for BP Amoco. Both international human rights groups and the guerrillas have been quick to draw international attention to alleged human rights abuses by armed forces deployed to protect BP Amoco's installations in Casanare Department. Other allegations point to army collaboration with local right-wing paramilitary activity.

While the Colombian authorities have cleared BP Amoco of any involvement-direct or otherwise-in human rights abuses, as long as the conflict continues, oil companies face a risk of exposure to damaging allegations. It is inevitable that the guerrillas will exploit the presence of state security forces around oil installations to allege that paramilitary terror tactics are used to crush any local opposition to oil development and its consequences.

The recent growth of the paramilitaries-now grouped under the United Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC)-and their geographical expansion suggest that the paramilitary groups will continue to pose a serious reputational risk for foreign oil companies. Conflict between paramilitaries and guerrillas for territorial control of key regions have intensified. Much of this is taking place in and around oil-producing areas.

In short, as long as the civil conflict continues, allegations that foreign oil companies are in any way connected with human rights abuses will carry the potential to cause more-serious and longer-lasting damage to a company than occasional bombings, sabotage, and extortion.

Kidnapping

Colombia is notorious for its kidnapping rate for good reason. And there is no sign of a let-up.

According to official statistics published in early August 1999, there were 1,354 reported kidnappings in January-July, an increase of more than 20% compared with the same period in 1998. There was a total of 2,609 reported cases in 1998, up 30% from 1997. Rebels are responsible for two-thirds of the kidnappings reported as of early December 1999. Around 40 foreigners were abducted in 1998.

Most kidnap victims are Colombian, and the statistics are inflated by the high number of security force personnel held by the guerrillas. But kidnappings of foreign oil company employees occasionally hit the headlines, especially when the victim is foreign. The logic is simple: the rebels' war chest is better filled by the larger ransom that a foreigner commands.

There were 23 oil-sector related kidnappings in the first 10 months of 1999, 11 of which were of foreigners. Abductions range from short-term detentions to long-term selective kidnappings for ransom that can last for months. They sometimes result in death.

Some abductions of foreign oil workers are planned, but many occur when basic security precautions are not observed. In November 1998, French geologist Claude Steinmetz was seized in Agua Azul in Casanare. Steinmetz was kidnapped while running outside BP Amoco's main Cupiagua oil installation. According to local press reports, the local front of the ELN in March 1999 called the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to recover his body. Steinmetz reportedly died of a heart attack while in captivity.

More recently, suspected guerrillas kidnapped British oil worker Alistair Taylor as he traveled from Yopal, the capital of Casanare, to a nearby village. Taylor was working for the industrial engineering firm Weatherford Colombia under contract to BP Amoco.

For the victim, the experience can be traumatic. For the company, a kidnapping can have a number of negative consequences: unwelcome media exposure, management time spent dealing with the incident, protracted exposure to extortion demands, a negative impact on worker morale, and both ethical and financial considerations about how a company should best protect its personnel.

In the early stages of peace talks, the guerrillas have expressed a willingness to negotiate their stance on kidnapping, but only if difficult conditions are met. Ideologically, the rebels remain committed to kidnapping, which they see as just another justifiable form of war tax. For the foreseeable future, abduction of personnel and the attendant consequences will remain a real risk for foreign oil companies operating in Colombia.

Guerrilla tactics

The guerrillas employ various tactics to target and extract economic benefit at different stages of an oil project's development. Their strategy is to maintain control over economic activities that they consider as falling within their territory.

At the preliminary study stage, the guerrillas identify projects under consideration and contact the people responsible for gathering preliminary information. The guerrillas facilitate travel in the area and provide operational support, claiming that they do this because they consider the project offers economic and social benefits for the region.

At this stage, the guerrillas are unlikely to attack or try to impede the oil-related development. However, subcontractors have sometimes been targeted if they have had problems with insurgent groups in other parts of the country. On other occasions, subcontractors have been targeted by loosely organized criminal groups.

The guerrillas facilitate the preliminary studies in order to generate confidence and make contacts. This enables them to gather information on the projects and the companies involved. The guerrillas want to assess the possibility of infiltrating the companies or of participating in the projects by using front companies. In some cases, subversive groups take control of land in the project area in order to profit from its subsequent exploitation.

At the exploration, construction, and well-drilling stages, the guerrillas seek to make contact with the operating company, either directly or through the local community, in an effort to influence the social and economic investments related to the project. Simultaneously, the guerrillas initiate a three-pronged pressure campaign:

- Dissemination of written communications (boleteo) requesting provisions, medical supplies, or the implementation of social projects.

- Extortion, through direct, telephone, or written contact, demanding financial contributions to their armed struggle.

- Low-level terrorist attacks.

These actions are usually directed against subcontractors, which are usually from outside the region or foreign. Only rarely are such actions taken against the operating company.

At this stage, the subversive groups want to demonstrate to the companies their regional power and their capacity to destabilize a project and to show that they can use this to extract economic benefits from an oil project when it enters the production phase.

If the project does not progress to production, the guerrillas will use extortion or kidnapping to pressure the operating company or international oil company into withdrawing from the region. If this is not viable, the guerrillas may declare the operating company to be a military objective, using terrorist attacks to cause the greatest possible damage. This can have repercussions in other parts of the country where the company may have operations.

At the production stage, the guerrillas employ the following strategies to exert their influence over an oil project. It includes the following tactics:

- Infiltrate the various companies participating in a project.

- Organize and influence the local community groups and unions.

- Through these groups, the guerrillas exert pressure in order to attain economic benefits. They create front companies; divert oil royalties; pressure for the implementation of local development projects; and influence labor policies, directly or by manipulating unions in matters affecting wages, severance pay, equal treatment for foreigners and Colombians, etc.

This stage affects the operating company and subcontractors and can generate social, economic and security problems that may force the company to withdraw from the areas.

Cautionary tales

The following case studies show how some oil companies have managed or failed to manage the security risks posed by the guerrillas.

What to do?

The above scenarios illustrate how difficult it is for oil companies to operate successfully in Colombia. Most of the oil companies working in Colombia have, to a greater or lesser degree, experienced the above problems. Many continue working profitably despite the security problems and attempt to minimize the risks. Other companies reduce the scale of their operations or leave the country for, among other considerations, security reasons.

Nonetheless, it is possible to reduce security risks considerably. The first step is to undertake an in-depth study of the social, economic, political, and security situation in the region concerned. This should be done before seeking environmental and other permits. Such a study will help the company to pre-empt the risks in each area. However, it must be stressed that the risks vary considerably from one region to another.

The company can now draw up security schemes that are preventive rather than reactive. This may involve constant intelligence-gathering and working with regional environmental and community groups. The approach does not involve extreme physical security or extensive use of private or state security forces. Instead, it involves a mix of preventive security measures that will oblige the guerrillas to keep a distance from the project.

Recent developments

Few companies are carrying out significant down-sizing of their operations in Colombia, despite the gravity of the security situation. Where the size of an operation has been reduced, it is usually as part of the company's long-term strategy. This is particularly true in the oil sector. Completion of the construction phase of BP Amoco's Cusiana-Cupiagua oil project is the main reason for the reduction of that company's personnel in Colombia. BP remains firmly committed to the project because of its high profitability.

However, the overall consensus among foreign companies is that the security environment has deteriorated considerably in the past 18 months and that this could act as a brake on future investments.

Some companies are reducing the number of expatriates that are deployed, especially those in remote regions that are particularly vulnerable to terrorist and criminal attacks. This mostly applies to companies involved in the extractive sectors. These companies are increasingly using the strategy of so-called "Colombianization" of operations. This involves wherever possible using Colombian nationals rather than expatriates to manage operations in dangerous areas. But most foreign companies are not considering a total withdrawal of the expatriate work force at the present time.

Another important factor is the difference of opinion between head offices (particularly in the US), and executives on the ground in Colombia. Expatriate executives in Colombia do not generally believe that the current situation is as bad as is sometimes reported. Executives in head offices are more inclined to consider a reduction or withdrawal of the expatriate work force.

Because of the current heightened security risk, many companies are preparing or revising contingency and crisis management plans. These actions are based on the perception that the situation is likely to deteriorate further over the next 12 months. Some companies as a precautionary measure are preparing evacuation plans for their staff and for the possible future relocation of operations.

Companies are imposing tight restrictions on travel by their personnel. As the travel situation can change daily, companies are also seeking to improve their information-gathering. Some companies have restricted the movement of expatriate personnel within and close to Bogotá, insisting that they take common sense precautions such as not going out after dark and not visiting high-risk areas at times when guerrilla attacks are anticipated.

Companies are also reassessing whether visitors and executive personnel need to come to Colombia. Some have stopped non-essential travel to Colombia. Those who do travel to Colombia tend to stay only for a minimal period and avoid spending extra time or remaining in the country for recreational activities.

BP Amoco, for example, has adopted a policy of flying expatriate employees directly in and out of Casanare in order to avoid expatriate families having to live in Bogotá, which the company considers to be a high-risk location.

But the attitude of the regional manager of one US-based oil services company is perhaps typical. Although he warns that the security situation in Casanare and Bogotá has deteriorated sharply in the past 2 years, he would only consider withdrawing from the country for economic reasons such as a collapse in demand for the company's services.

His company in 1999 received threatening telephone calls warning that the local manager in Yopal (Casanare) should leave the country within 24 hr. The regional manager thought that a disgruntled former employee, who was known to have had links with the local guerrillas and paramilitaries, was probably responsible. The company did not take any action, and the threat was not carried out.

Nevertheless, the manager considers that the guerrillas maintain detailed information about foreign companies operating in Colombia and about their expatriate and local employees, and that control of such information is critical.

The Author

John Wade is Senior Analyst (Americas) for Control Risks Group information services. He specializes in analysis of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. Before joining Control Risks Group in 1996, he worked as a journalist in Venezuela.