Uncertainties plague Indonesia's gas development projects

A cloud of uncertainty hovers over prospects for Indonesia's natural gas sector.

Indonesia's economic recovery continues to be plagued by unfavorable domestic events that include bickering among the elite, separatist movements, clashes between religious groups, corruption scandals, and the never-ending demonstrations.

As far as economic recovery is concerned, these events hamper market confidence and certainly discourage foreign investment.

The government, under the democratically elected Pres. Abdurrahman Wahid, faces many challenges; yet it is believed that improved economic performance will ultimately be the key to successfully confronting these daunting domestic problems.

One of the few bright spots within Indonesia's economic parameters is its favorable external trade balance.

Trade balances continue to improve (Table 1), despite sluggish manufacturing export performance. This has, in turn, improved the balance of payments and foreign exchange reserves.

Higher prices for oil (and consequently for LNG) have played a major role in helping improve the country's trade balance. In 1999, Indonesia's oil and gas exports increased by 24% over the previous year, thereby increasing much-needed government receipts to meet the targeted budget.

However, it is obvious that the contribution of the oil trade continues to shrink relative to that of natural gas (Fig. 1). This is because stagnating crude oil production, amid increasing consumption, requires importation of both crude oil and refined products.

Because Indonesia's gas reserves are potentially much larger than its oil reserves, it is expected that natural gas will play an ever-increasing role in trade as well as in fueling domestic energy needs.

Despite its importance, however, the growth of Indonesia's natural gas sector is currently subject to many uncertainties. Major issues continue to affect natural gas development, including separatist movements in the resource-rich provinces, the unclear fate of the new oil and gas law, and the subsidy of petroleum product prices.

Separatist movements

The current domestic political crisis includes secession efforts by the resource-rich provinces of Aceh, Riau, East Kalimantan, and Papua (formerly known as Irian Jaya).

All current LNG supplies come from Aceh and East Kalimantan. And, in addition to being the source of almost half of the crude oil produced in the country, Riau Province includes the territory of the Natuna Islands, which have the largest gas reserves in the country.

With reference to its resources, Papua is better known for the Freeport copper (and gold) mine, but the recently discovered Tangguh gas field also is located there.

Combined, all these provinces contain more than 80% of the country's total gas reserves (Table 2).

Aceh and Papua pose the greatest threat of separation, although the government will try to keep the whole country intact by offering autonomy to the provinces, along with greater shares of income from the extraction of resources.

As a precedent, the government recently offered the Riau local government a participation in the development of the Coastal Plains Pakanbaru oil field after the production-sharing contract (PSC), currently held by Caltex Petroleum Corp., expires in 2001.

Prior to this newly proposed arrangement, the government had decided to have both Caltex and Indonesia's state-owned oil and gas company Pertamina jointly operate the field without any participation by the local governments.

Obviously, Aceh is the most critical concern. The problem in Aceh is not solely its unfair treatment regarding resource income but also discontent fed by years of governmental mishandling of the provincial population. During the rule of the Suharto government (1967-98), military oppression caused many human rights violations in Aceh.

The leaders of the separatist movement claim that the majority of Acehnese want to be totally separated from Indonesia. Consequently, the outcome of Aceh is very uncertain.

The other provinces, however, may be content with greater autonomy and higher shares of income from the extraction of their natural resources.

Nonetheless, the Indonesian government must come to terms with all of these issues before political confidence can be restored. The current state of unrest will likely delay any gas projects in these provinces, most notably development of BP's Tangguh field for LNG in Papua.

Oil subsidy vs. domestic gas incentive

The unclear fate of new oil and gas legislation also creates uncertainty from an institutional point of view.

The current government has proposed an oil and gas bill to establish a gas price based on market forces after a similar effort proposed by the previous government fell through in September 1999. The legislative body (DPR, or House of Representatives) was scheduled to deliberate the bill last month (OGJ Online, Sept. 14, 2000).

The major issues do not pertain only to the income shares between local and central government, as previously discussed. They also include, among other things, which institution will be responsible for issuing licenses for new PSCs (currently handled by Pertamina), deregulation in the oil sector, and Pertamina's role in the new set of rules and regulations.

One of the issues in the deregulation of the downstream oil sector is whether the domestic market will eventually be liberalized. Indeed, one of the major hindrances to the use of natural gas in the domestic market is the extremely low price of petroleum products, most notably middle distillates (Table 3).

The government was supposed to raise the prices by an average of 10% last April, but it backed down due to fierce opposition by political parties and mass demonstrations against the move.

Although the government has pledged that it will eventually phase out the subsidy, implementation during the economic crisis will be sketchy at best, especially when the Indonesian currency continues to depreciate against the US dollar.

Despite this inherent constraint, the industry and the government continue to find ways to increase domestic gas use.

Following the suggestions of the Indonesian Petroleum Association, the government has agreed to give more incentives for domestic gas use by lowering the total receipt from the government take (i.e., government share plus taxes) while maintaining the net take of production-sharing contractors.

Consequently, the price of natural gas to the domestic consumer can be reduced by as much as 50¢/MMbtu. The target prices include $2.00 for electric power generation and about $1.50 for other industrial uses, including feedstocks for fertilizers.

Although the government agrees to this scheme in principle, implementation will still require some institutional setting derived from the new oil and gas law.

Export market

In the export market, Indonesia is still the world's largest LNG exporter, and despite the apparent decline of production from ExxonMobil Corp.'s supergiant Arun field in Aceh (OGJ Online, July 17, 2000), the country will have no problems meeting its contractual obligations.

Given the continuing new gas finds, the rising production from East Kalimantan will apparently make up for the reduced production from Arun.

Fig. 2 shows the development of LNG production from both Arun and Bontang in East Kalimantan. Because Arun also supplies the area's gas processing plants, its decline in production has been reflected in total LPG exports (Fig. 3).

Future expansion of LNG exports depends not only on whether there will be any additional demand from potential buyers but also whether the country is able to develop the vast and uncommitted gas resources in time to penetrate the market.

The uncertainty within Papua Province will hamper development of BP's Tangguh field, which has a proven reserve of at least 15 tcf. Given its proximity to Far Eastern buyers, Tangguh has a good chance of materializing amidst fierce competition from other LNG suppliers.

Meanwhile, the potential for supply from ExxonMobil's Natuna gas field is still considered a long shot because its high CO2 content makes the cost of operation there high.

Continuing new gas finds in East Kalimantan warrants at least one additional LNG train at Bontang. However, expansions beyond one train may face a site constraint.

In the meantime, exporting gas via pipeline is becoming a reality. Pertamina has signed a contract to deliver 325 MMscfd of gas to Sembawang Gas Corp. in Singapore for 22 years.

The gas will be delivered via a 650-km subsea pipeline from West Natuna starting in 2001 (OGJ Online, May 11, 2000). A consortium that includes Conoco Inc., Gulf Indonesia Resources Ltd., and Premier Oil PLC will supply the gas.

Another potential supply of pipeline gas to Singapore is on the horizon as well. Pertamina signed a letter of intent in September 1999 with PowerGas Ltd., a unit of Singapore Power Co., to supply natural gas to Singapore Power for 20 years (OGJ, Oct. 4, 1999, p. 38).

Other involved parties include producers Gulf Indonesia and Santa Fe Snyder Corp., which will deliver gas from their fields in Central Sumatra. The Indonesian gas distribution company PT Perusahaan Gas Negara will transport the gas to the Singapore border.

According to the gas sales plan, Singapore Power will initially purchase 150 MMscfd starting in mid-2002 and will gradually increase purchases to 350 MMscfd by 2008. Under the letter of intent, the price of the piped gas will be pegged to 115% of the Singapore spot price for high-sulfur fuel oil.

Major players in Indonesia

Given the demographics of Indonesia, natural gas reserves near the demand centers are utilized domestically, while reserves that are remotely located, away from domestic consumption, are destined for export. Therefore, most of the gas reserves have been developed in or near Java, the most populated island.

Indonesia currently produces about 8.5 bscfd of natural gas. LNG plants dominate gas utilization (Fig. 4) by using over 50% of the country's total gross production.

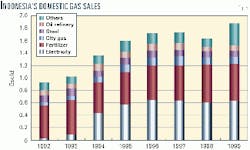

However, the domestic use of natural gas has continued to rise, especially before the economic crisis. During 1992-97, domestic sales increased by 13%/year. As a result of the crisis, domestic gas sales declined in 1998 but had again picked up in 1999. Fig. 5 shows domestic sales of gas by major buyers.

Electric power generation and fertilizer production are currently the two sectors providing the base demand for Indonesia's gas consumption. However, the future outlook for these two sectors will likely differ.

Fertilizer plants have enjoyed some price subsidies, paying as little as $1/MMbtu, whereas the electric power generation industry pays the market price. It will therefore be difficult for producers to supply the fertilizer industry if the price will not warrant it.

Consequently, the power sector will be the primary target for gas market penetration, especially when the government implements the domestic gas incentive. Currently, the power sector is characterized by oversupply, but demand will once again increase as economic growth increases.

In 1999, a pronounced rise in demand in the "Others" category in Fig. 5 was the result of the massive steamflood project in giant Duri oil field that consumes about 260 MMscfd of natural gas. Prior to the use of gas, as much as 50,000 b/d of Duri crude was burned directly as fuel to generate the steam.

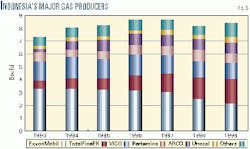

In Indonesia, foreign oil companies produce most of the gas. Currently, these firms produce more than 90%-whereas Pertamina produces about 8%-of the country's gross production.

Mobil Oil Corp. (now ExxonMobil) used to dominate production, but the decline in Arun deteriorated its share of total production. Given its ever-increasing production in East Kalimantan, TotalFinaElf SA is expected to overtake the position of the largest gas producer in Indonesia in 2000 (see related article, p. 50). Fig. 6 shows Indonesia's major gas producers.

In 1999, ExxonMobil's share of Indonesia's total gas production was about 26%, followed by TotalFinaElf, 22%; Virginia Indonesia Co., 16%; ARCO (now BP), 10%; Pertamina, 8%; and Unocal Corp., 5%. Other producers have the remaining shares. With foreign companies playing such an important role in the production of Indonesia's gas, further exploration and development are imperative, but they are subject to the companies' perceptions of the previously mentioned uncertainties.

Conclusion

In the contribution of the hydrocarbon sector to external trade, Indonesia will have to rely more on gas export revenues, because net oil receipts will continue to shrink. Indeed, the oil sector will likely generate negative receipts in the near future.

Compared with its oil, Indonesia's natural gas reserves are quite ample. However, future development of gas resources, both for export and domestic use, will face many uncertainties.

First and foremost, the country needs to solve its problems related to the unhappy provinces that host most of the gas resources. Second, a more appropriate oil and gas law will be necessary to accommodate the new setting.

All of these will be necessary conditions for the future participation of foreign firms that will provide capital expenditures in the exploration and production of Indonesia's resources.

And last, the subsidy of petroleum products must eventually be eliminated if gas is to play a more significant role in Indonesia's domestic energy mix.

The author

Widhyawan Prawiraatmadja is a senior associate and project director with Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services Inc. (FACTS), Honolulu, and is director of projects for East West Consultants International Ltd. He also is coordinator of the petroleum market and refining project of the East-West Center energy program. In the commercial energy sector, he has conducted research relating to economic, environmental, and government policy issues. In the oil sector, his research focuses on deregulation and privatization policy, crude oil and petroleum products pricing, refinery modeling and economic analyses, and environmental considerations in petroleum products specification. He has authored several publications and journal articles and serves on the board of the Indonesian Institute for Energy Economics. Prior to coming to the US in 1989, Prawiraatmadja was energy division manager with PT Redecon in Jakarta. He has an MA in economics from the University of Hawaii and a BS in industrial engineering from Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia.