“I really don’t think there’s been a time since I’ve been in our industry where inventories and spare capacity are both very low.”

Vicki Hollub’s statement on Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s second-quarter earnings conference call in mid-May was a bold one. But the 35-year veteran of the $26 billion Houston-based company—and its president and chief executive officer since 2016—has the roots to make that call. Speaking to analysts about the headwinds producers face as they look to raise output, she said the cost of materials, equipment, and workers have created something worse than a zero-sum situation.

“We can’t destroy value and it’s almost value destruction if you try to accelerate anything now,” Hollub noted. “Some of the longer-term projects just can’t get started because of the cost involved.”

Pipes, valves, sand, and trucks all are part of the tight supply situation, but one could make the argument that suppliers will in the coming months find ways to alleviate the shortages of those goods. Another key factor, labor, could be a longer-term problem as producers look to grow. Research firm Rystad Energy says US oil and gas companies trimmed their payrolls by about 200,000 drilling, construction, support, and services jobs in 2020 and 2021. And while they’re on pace to recover half of that number this year, the remaining gap is substantial and will be difficult to fill.

Rystad analysts said in May that oil and gas employment in the US should this year climb more than 12% to 971,000. But that number will still be nearly 10% below the sector’s pre-COVID level, a mark the Rystad team thinks will be passed only in 2027. That equates to a forecasted annual growth rate of 2.3% for the next 5-plus years.

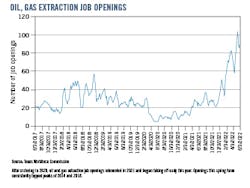

The need for workers started to manifest early this year in the Permian basin as world markets bid up crude prices past $100/bbl after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Oil and gas extraction job openings tracked by the Texas Workforce Commission climbed to a weekly average of about 80 in March from 43 in the first 6 weeks of the year and were well above 90 in May. Those numbers are about triple the average from 2018-19 (see accompanying figure).

The push is on (again) to find workers, and quickly, given comments from Hollub and several of her peers about the competition and beggar-thy-neighbor nature of investment in the Permian basin and beyond. And companies will have to pay more for that talent for much of this decade: Rystad is expecting annual wage growth of more than 7% through 2027. That’s in part because the industry is going to have to replace veteran workers who have moved on in recent years and because companies will need to compete more strenuously for young talent that is increasingly looking to the renewable energy sector or other industries on an upswing.

Experts say succeeding in that environment will require some good storytelling from industry stakeholders, both about the nature of today’s work and the opportunities to be a part of the massive shifts that lie ahead.

“These jobs still have a stigma of being dirty and dangerous even though there’s a huge safety culture and they’re becoming more automated,” said Jeff Pearce, coordinator of education and workforce efforts for the LyondellBasell Center for Petrochemical, Energy & Technology at San Jacinto College in the Houston area. “But we’re breaking that stigma and see a lot more women and people with nontraditional backgrounds coming in.”

The scope of many jobs also has evolved, Pearce said. Like many other industries, candidates and young professionals looking to succeed today often need software, analytics, and operating systems skills that their peers of a few years ago could overlook. And that has more companies delving deeper into the educational system and connecting with STEM-interested students in high schools and junior high schools, Pearce said. With technology companies as well as sectors such as manufacturing and logistics providing greater competition for students with science and mechanical leanings, the oil and gas sector is having to recruit more fiercely than ever.

“I don’t see the number of field workers needed coming down, but companies are being more selective,” he said. “Workers have to know what they’re looking for and looking at. They have to have a little more of an educational background.”

They also have to be open to additional post-degree training. Students Pearce and his team at San Jacinto College send into the working world typically get between 6 months and 2 years of additional training in technical skills and safety measures. Tracy Josefovsky, vice-president of human resources at Halliburton Co., says the oilfield services giant knows it needs to do its part to build on the foundations of young or new-to-the company employees. The combination of electrical or mechanical aptitude and digital literacy “can be hard to find in this labor market,” Josefovsky said, but Halliburton leans on its training programs to round out workers’ skills sets. Last year, workers clocked more than 1.4 million hrs of training, including at Halliburton’s Data Science Academy.

“This allows us to focus less on specific degrees that constrain our talent pools and more on hiring bright, hard-working people,” she said. “If someone is hard-working and eager to learn, we can help with the rest.”

Watching the big picture

Training programs also serve the dual purpose of improving employee retention rates and lifting the productivity of various teams, with both of those factors growing in importance as labor and production costs climb. David Meats, director of research on energy and utilities at Morningstar, noted that a handful of executives of publicly traded producers this spring guided to the high end of their companies’ projected 2022 capital spending ranges because of inflation pressures, not because they’re adding projects.

All-in well costs are expected to climb 10-15% this year, but Meats said that number could change because it includes some costs from contracts signed late last year that have risen since. Updates to various contracts will begin to show up in second-half 2022, Meats said, and really show themselves in 2023.

Hence the need and desire for efficiency gains along the lines of what Robert Geddes, president and chief operating officer of Ensign Energy Services Inc., described on his team’s May conference call. Asked about cost pressures and the potential for them to cause client losses, Geddes was confident.

“We’re drilling wells in a third of the time that we did five, six years ago” he said. “So, we’ve been creating real value to the client. They understand the market. They understand the wage increases for the crews.”

While such efficiencies are often hard-won and there is a time lag to bringing new labor to an appropriately productive level, Meats said the trend could continue.

“If you had bet on labor efficiency being down at any point in the past 10 years, you would’ve been wrong,” he said. “And it would be a mistake now to assume that the low-hanging fruit is gone.”

It’s a good story for the industry to tell in the recruiting wars: “We’ve made real changes to how we operate. We have better equipment that we run more smartly. We’ve become cleaner and will continue to do so.”

That last angle holds huge promise, San Jacinto’s Pearce said. Many of the technical and safety skills engineers and other production workers learn for oil-and-gas work transfer nicely to clean-energy projects. And companies moving into carbon capture and sequestration have a leg up in selling themselves to young talent. Halliburton’s Josefovsky said the company has had success bringing new people to the industry by highlighting its work on geothermal, decarbonization, and other emissions-reducing projects as well as its Hal Labs clean-tech accelerator.

“They know it’s a big deal and they want to be sure they’re doing their part,” Pearce said of notable names investing in transition initiatives. “What we hear regularly is, ‘We really want to be good neighbors.’”

As hiring companies increasingly get in front of younger students, Pearce said they’ll do well to show their involvement in green investments. It is key, he said, to get word out early during this changing energy age.

“It’s not activists or governments that will make this transition happen,” he said. “It’s the companies. Their initiatives will be the ones that make this work.”

About the Author

Geert De Lombaerde

Senior Editor

A native of Belgium, Geert De Lombaerde has more than two decades of business journalism experience and writes about markets and economic trends for Endeavor Business Media publications Healthcare Innovation, IndustryWeek, FleetOwner, Oil & Gas Journal and T&D World. With a degree in journalism from the University of Missouri, he began his reporting career at the Business Courier in Cincinnati and later was managing editor and editor of the Nashville Business Journal. Most recently, he oversaw the online and print products of the Nashville Post and reported primarily on Middle Tennessee’s finance sector as well as many of its publicly traded companies.