North Africa carbonates exhibit unique geomechanical properties

Nadia Haddoum

Belkacem Lotfi Sekat

Akli Abdennour

Farid Belfar

Sonatrach

Algiers

Fethi Bensenouci

Vincenzo De Gennarro

Rabah Lamali

Schlumberger

Algiers

Geomechanical analysis of North Africa carbonates revealed rock property correlations which significantly deviated from those in analog fields. The results confirm the singularity of these carbonates and highlight the importance of conducting laboratory tests before drilling or field development.

Carbonate formations in North Africa are difficult to drill, leading to wellbore instability. Nonproductive time, poor wellbore quality, and reservoir damage have all occurred from insufficient understanding of rock mechanical behavior. Rock properties provide input for stress calculations and wellbore stability analyses, but none were available for the North Africa Upper Cretaceous carbonate formations of interest.

Core properties previously been obtained in North Africa came from carbonate formations, the only type of reservoir presently producing. To address deficient core data for North Africa carbonates, a geomechanical study tested 44 cores for Young’s modulus (E), Poisson’s ratio (PR), Biot constant, unconfined compressive strength (UCS), internal friction angle, and tensile strength.

Typically, these properties are not acquired through cores but calculated using sonic and density log data with empirical models. However, the study results show that without core data, models derived from log data and empirical correlations from literature can lead to significant errors.

Material, methods

After drilling each exploration well, cores were removed, cleansed with water, and stored in the company core shack. A mixed team of geologists, petrophysicists, and geomechanic engineers selected cores for geomechanical analysis to cover maximum vertical and lateral heterogeneity in the limestones. Core selection was based on location in the reservoirs, open-hole log availability, well quality, and core description (e.g. lithology and presence of fractures, Fig. 1). Test cores consisted mainly of Upper Cretaceous limestones. These bioclastic carbonates are hard-to-medium hard and characterized by white, beige and gray-to-dark gray colors. Porosity (f) varies from 3% to 29% and permeability (k) varies from 0.4 mD to 100 mD.

The 44 cores from 11 wells yielded 377 plugs. Before cores were destructively tested, petrophysical and acoustic tests measured porosity, density, permeability, compressional velocity, and shear wave velocity.

UCS testing of core samples preceded triaxial tests. During these tests, axial and lateral rock deformation were simultaneously measured when loading, using a strain gauge glued to the core.

The 2 × 1-in. rock plugs underwent conventional triaxial compression tests. The triaxial cell is a transparent polycarbonate chamber which has a piston assembly on top and a double flange base on bottom. Triaxial compression tests are conducted at constant axial stress rate of 0.2 MegaPascals/min (MPa/min). Confining pressures are half, equal, and double lithostatic stress, estimated from field overburden stress of each plug location, and Poisson’s ratio, estimated from the UCS.

Results

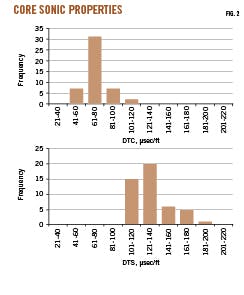

The carbonate cores exhibited consistent 3% porosity with an average density of 2.65 g/cu cm. Acoustic measurements were expressed as acoustic slowness instead of velocity (Fig. 2). Compressional slowness (DTC) varied from 50 µsec/ft to 102 µsec/ft, averaging 72 µsec/ft. Shear slowness (DTS) varied from 103 µsec/ft to 184 µsec/ft, averaging 131 µsec/ft. These values are in the same range of acoustic slowness measured in carbonates around the world.1-3

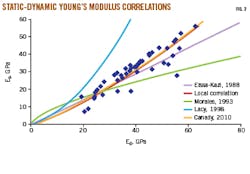

Fig. 3 compares dynamic Young’s modulus (Ed) calculated from core sonic properties using Gassman equations with static Young’s modulus (Es) obtained from core measurements.4 Compared with literature correlations, the cores showed different tendencies, except for Canady’s correlation which aligned with previous data.5 Canady’s correlation was constructed on a wide range of rock and can be calibrated for specific lithotype. The inconsistencies between the local and most literature correlations confirmed the wider heterogeneity of limestones compared to sandstones.

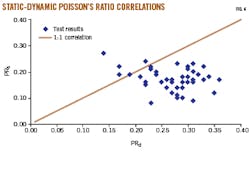

Fig. 4 compares dynamic Poisson’s ratio (PRd) from logs to static measurements (PRs) from cores. There is no clear correlation between static and dynamic Poisson’s ratio. Overall, dynamic Poisson’s ratio values calculated from acoustic measurements exhibited higher values than static Poisson’s ratio by an average of +0.12. This difference is substantial knowing that dynamic and static Poisson’s ratio often are considered similar in geomechanical studies.6 The results show that this assumption is misleading and can result in erroneous stress calculations. The results are also consistent with the observation that Gassmann-derived Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio usually need correcting due to the high frequencies under which the measurement of acoustic velocities is performed as compared with compression tests.

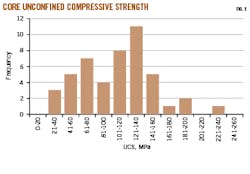

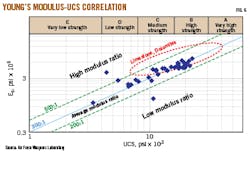

UCS measured from core ranged from 23 MPa to 200 MPa with an outlier at 230 MPa (Fig. 5). In the graph by Deere and Miller, 75% of the results lie within carbonate boundaries for intact sedimentary rocks (Fig. 6).7

Fig. 6 also shows that most of the data fall in the average, medium, and high strength modulus ratio zones. This position is a response to both the texture and mineralogy of limestone. Remaining lab data showed a lower strength zone (D zone) which falls out of the limestone envelope, possibly from marls or clayey material in the selected plugs.

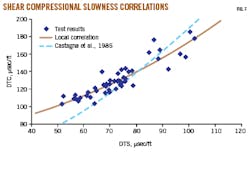

Table 1 summarizes correlations between the different parameters. Equation 1 can be used to derive shear slowness from compressional logs. Shear slowness logs are often lacking in well data sets and are usually acquired from gamma ray (GR) during logging operations in exploration or development wells. Fig. 7 shows that acoustic data are aligned along an exponential correlation with a good correlation coefficient. By comparison, the commonly-used Castagna’s correlation crosses the local DTS vs. DTC correlation at DTC = 80 µsec/ft, overestimating shear slowness above, and underestimating below, this value.8

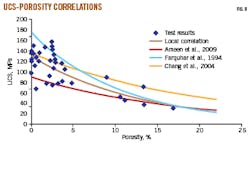

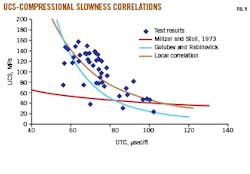

Calculating UCS in carbonates using wireline or LWD logs requires a series of empirical correlations linking UCS to porosity, DTC, and Es.9-18 These correlations are plotted in Figs. 8-10 based on the corresponding correlation equations in the table. Empirical literature carbonate formation relationships are shown for comparison.

Fig. 8 shows that UCS is inversely proportional to porosity. The data follow an exponential trend with correlation coefficient R2 = 0.66. The same trend has been proposed by Farquhar, Ameen, and Chang. Note that equations of Farquhar and Ameen bracket the present results at higher and lower UCS, respectively. Considering the low measured porosities and discrepancy of corresponding UCS values, the use of these literature correlations to calculate UCS for all of a given formation is questionable.

UCS, DTC

As DTC is the most available log with GR, correlations grouping UCS and DTC have been proposed in several studies to obtain UCS from well logs. In the case of North Africa carbonates, UCS is inversely proportional to DTC, following a power trend line with a correlation coefficient R2 = 0.54 (Fig. 9). The Golubev and Robinovich correlation suggests a similar trend but underestimates core measured UCS. On the other hand, the correlation of Milizer and Stoll presents much less variability of UCS with acoustic slowness. It tends to drastically underestimate UCS for DTC of less than 80 µsec/ ft.

UCS, Es

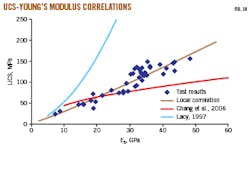

UCS appears better correlated with static Young’s modulus compared to compressional slowness and porosity (Fig. 10). Es shows large variability compatible with the wide range of measured UCS. The UCS vs. Es relation is a power law with correlation coefficient R2 = 0.9. Correlations of Chang and Lacy are inconsistent with the trend and tend either to overestimate (Lacy) or underestimate (Chang) UCS.

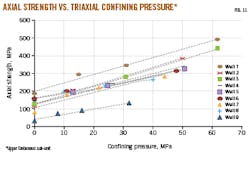

Fig. 11 shows UCS compared with axial strength from triaxial tests. Overall, axial strengths derived at zero confinement from triaxial tests match measured UCS. Moreover, and with minor discrepancy, the failure curves are straight lines in agreement with linear failure models like Mohr-Coulomb.

References

- Chang, C., Zoback, M.D., and Khaksar, A., “Empirical relations between rock strength and physical properties in sedimentary rocks,” Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Vol. 51, No. 3-4, May 16, 2006, pp. 223–237.

- Carmichael, R.S., “Handbook of Physical Properties of Rocks,” Vol. 2, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla., 1982.

- Lama, R.D. and Vutukuri, V.S., “Handbook on Mechanical Properties of Rocks,” Vol. 2, Trans Tech Publications, Clausthal, Germany, 1978.

- Gassmann, F., “Uber die Elastizitat poroser Medien,” Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellscaft in Zurich, Vol. 96, No. 1, 1951, pp. 1-23.

- Canady, W., “A Method for Full-Range Young’s Modulus Correlation,” SPE 143604, North American Unconventional Gas Conference, The Woodlands, Tex., June 14-16, 2011.

- Burshtein, L.S., “Static and Dynamic Rock Tests [in Russian],” Izd. Nedra, Moscow, 1970.

- Deere, D.U. and Miller, R.P., “Engineering Classification and Index Properties for Intact Rock,” Technical Report No. AFWL-TR-65-116, Air Force Weapons Laboratory, Kirtland, NM, 1966.

- Castagna, J.P., Batzle, M.L., and Eastwood, R.L., “Relationships between compressional-wave and shear-wave velocities in elastic silicate rocks,” Geophysics, Vol. 50, No. 4, Apr. 1, 1985, pp. 571-581.

- Smorodinov, M.I., Motovilov, E.A., and Volkov, V.A., “Determination of Correlation Relationships Between Strength and Some Physical Characteristics of Rocks,” Proceeding of the Second Congress of the International Society for Rock Mechanics, Beograd, Sept. 21-26, 1970.

- Rzhevsky, V. and Novick, G., “The Physics of Rocks,” Mir Publishers, Moscow, 1971.

- Militzer, H. and Stoll, R., “Einige Beitrageder geophysics zur primadatenerfassung im Bergbau,” Neue Bergbautechnik, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1973, pp. 21–25.

- Golubev, A.A. and Rabinovich, G.Y., “Resultaty primeneia appartury akusticeskogo karotasa dlja predeleina proconstych svoistv gornych porod na mestorosdeniaach tverdych isjopaemych.” Prikl. Geofiz. Moskva, Vol. 73, 1976, pp. 109–116.

- Edlmann, K., Somerville, J.M., Smart, B.G.D., Hamiton, S.A., and Crawford, B.R., “Predicting Rock Mechanical Properties from Wireline Porosities,” SPE/ISRM 47344, SPE/ISRM Eurock ‘98, Trondheim, Norway, July 8-10, 1998.

- Eissa, E.A. and Kazi, A., “Technical Note: Relation Between Static and Dynamic Young’s Moduli of Rocks.” International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences and Geomechanics, Vol. 25, No. 6, December 1988, pp. 479-482.

- Farquhar, R.A., Somerville J.M., and Smart, B.G.D., “Porosity as a Geomechanical Indicator: An Application of Core and Log Data and Rock Mechanics,” SPE-28853, European Petroleum Conference, London, Oct. 25- 27, 1994.

- Lacy, L.L., “Dynamic Rock Mechanics Testing for Optimized Fracture Designs,” SPE-38716, 71st SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, Tex., Oct. 5-8, 1996.

- Ameen, M.S., Smart, B.G.D., Somerville, J.M., Hamilton, S., and Naji, N.A., “Predicting Rock Mechanical Properties of Carbonates from Wireline Logs (A Case Study: Arab-D Reservoir, Ghawar Field, Saudi Arabia),” Marine and Petroleum Geology, Vol. 6, No. 4, April 2009, pp. 430-444.

- Santos, E. S. R. and Ferreira, F.H., “Mechanical Behavior of a Brazilian Off-Shore Carbonate Reservoir,” ARMA 10-199, 44th US Rock Mechanics Symposium and 5th U.S.-Canada Rock Mechanics Symposium, Salt Lake City, Utah, June 27–30, 2010.

The authors

Nadia Haddoum-Kherfellah ([email protected]) is a Sonatrach drilling project manager. She obtained her BS (1993) and MA (1998) in physics from Algiers University. She has a PhD (2017) in sciences and engineering materials from Boumerdes University, Algeria.

Fethi Bensenouci ([email protected]) is a Schlumberger senior geomechanics engineer for North Africa zone. He has an BS (1999) in civil engineering and PhD (2010) in earth sciences from the University of Paris-Sud.

Belkacem Lotfi Sekat ([email protected]) is a Sonatrach drilling engineer. He holds a BS (2003) in geology from USTHB university and an MS (2006) in drilling engineering from Sonatrach/IAP Boumerdes university.

Akli Abdennour ([email protected]) is a Sonatrach petrophysicist Engineer. He holds a BS in geophysics from Bab Ezzouar University (Algiers).

Farid Belfar ([email protected]) is a Sonatrach geologist project manager. He has a BS (1996) in geological engineering from the University of Algiers and a MS (2000) in geology of sedimentary basins.

Vincenzo De Gennarro ([email protected]) is geomechanics advisor, technical and business manager UK and continental Europe for Schlumberger. He graduated with a civil and geomechanical engineering degree (1992) and received his PhD (1999) at the Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussees – ParisTech, Paris.

Rabah Lamali ([email protected]) is senior geoscientist in SIS/data services for Schlumberger. He holds a geological engineer degree (2004) and MS in geology (2006) from Sciences and Technology, University of Algiers.