Study analyzes nine US, Canada shale gas plays

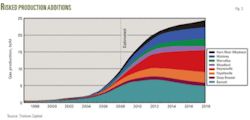

A recent study has estimated that nine US and Canada shale-gas plays may produce as much as 24 bcfd by 2018.

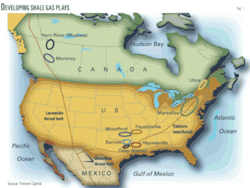

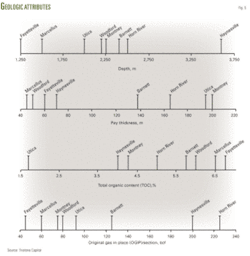

The Oct. 6, 2008, Tristone Capital Inc. study evaluated the gas resources in the Bamett (Fort Worth basin), Deep Bossier, Haynesville, Fayetteville, Woodford, and Marcellus shales in the US and the Montney, Hom River (Muskwa), and Utica shales in Canada (Fig. 1).

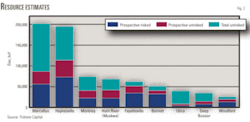

The study expects companies ultimately to recover from these resources 261 tcf of gas, based on various risk factors applied and a long-term average gas price of $8.50/MMbtu. Without the risk factors, Tristone Capital says these shales have a 743-tcf recovery potential (Fig. 2).

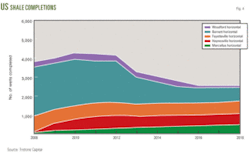

Fig. 3 shows the study’s estimated production from these plays, and Fig. 4 shows its US well completion forecast.

Several emerging shale plays with limited well control also may contribute additional gas to future production, according to the study. These include the Pearsall shales in the Maverick basin of South Texas, the Niobrara shales of Western Colorado, and the Barnett shale in the Delaware basin of West Texas.

Shale play comparison

The study says that shale-gas plays owe their success to a balance of various parameters along with constantly evolving drilling and completion techniques and infrastructure. “It is commonly said that no two shale gas plays are exactly alike,” the study says.

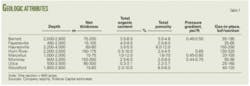

Table 1 summarizes shale-gas play attributes, and Fig. 5 compares the arithmetic average of the attributes. The study notes that the most productive core portions of plays may deviate from the averages.

Multistage hydraulic fracturing along a horizontal lateral and improvements in stimulation are main factors influencing shale-gas development economics. The study says these factors have improved economics by more than three times from that of vertical well developments by improving both ultimate recovery and initial production rates.

Table 2 compares typical lateral lengths and frac treatments for the nine plays.

The three types of frac fluid noted are slick water, CO2-polymer, and gelled cross-linked oil-based fluid.

Slick-water fracs use a nongelled fracturing fluid with low proppant concentrations and a friction-reducing chemical additive that allows pumping the water into the reservoir faster. The fluid often is a brine or potassium chloride (KCl) water to inhibit swelling of clays. The study notes that this fluid is less expensive than hydrocarbon-based fluid and works best in low-permeability reservoirs

Companies pioneered slick-water fracs first in the Fort Worth basin’s Barnett shale.

The CO2-polymer frac fluid contains emulsified CO2 in a methanol-water mixture of 5% water and 20% methanol. The study says the mixture appears to minimize reservoir damage and maximize fluid recovery from multiple diversions in the well. Including CO2 also reduces by 25% the fluid required and provides extra energy, as the gas expands, during frac fluid flow-back greatly to shorten cleanup time, the study says.

The Montney formation in British Columbia is where companies use this fluid. The study notes that stimulating a horizontal well in the Montney typically involves perforating, isolating, and fracturing 6-11 zones at a cost of about $100,000- 120,000/frac interval. It is common to spend more than $1 million for fracturing these wells, the study says. The study describes these jobs as needing 8-10 pump trucks or about 18,000-22,500 hp and taking more than 1 week to complete.

The study notes that companies initially used gelled cross-linked oil-based fluids as the “fluid of choice” for hydraulic fracturing because of its compatibility with most formations and its cold weather attributes. In several basins, slickwater fracs have replaced oil-based fracs because the slick water uses less water and costs less, the study says.

To prevent swelling and permeability loss in the shales, companies typically continue to use oil-based frac fluids in formations that contain extensive water-sensitive clays. The study notes that these fluids are used in the Fayetteville, Haynesville, and Woodford shales.

Fort Worth basin Barnett

Development activity continues to evolve with part of the current activity in urban sites such as Fort Worth and the Dallas-Fort Worth airports.

The study notes that as of Aug. 18, 2008, the Barnett had 8,416 gas wells drilled in 19 counties. Production had increased to 3.8 bcfd in first-quarter 2008 from 219 MMcfd in 2000. The study expects the shale to produce 6-7 bcfd in the next 5 years.

Some of the newer techniques in the play noted in the study are:

- Longer horizontal laterals, up to 3,500 ft, often drilled from pads with multiple wells, especially in the urban areas.

- Testing of tighter well density with laterals, spaced 250-ft apart (25-30) compared with 500 ft between laterals (50-acre spacing).

- Simultaneous fracing of wells to increase recovery.

Deep Bossier

Wells in Deep Bossier of East Texas reach a 15,000-20,000 ft depth, have pressures of about 15,000 psi, and have tested at 65 MMcfd. The study notes that these wells are expensive, costing $10-20/million for a vertical well.

Currently the play has six main fields in four counties: Robertson, Leon, Freestone, and Limestone.

Fayetteville

The Fayetteville shale in Arkansas is the shallower and thinner equivalent of the Barnett shale. The core of the play is in five counties in central Arkansas: Cleburne, Van Buren, Conway, Faulkner, and White.

The study says as of May 31, 2008, the play had 877 producing wells, with production in July of 740 MMcfd compared to only 90 MMcfd in December 2006. The study expects the play to produce 3.15 bcfd by 2018.

Haynesville

The Haynesville shale is in northwestern Louisiana and East Texas. Wells in the play initially have produced 5-20 MMcfd, the study said. The study expects wells to have ultimate gas recovers of 4-8 bcf.

Currently, companies have drilled about 20-25 horizontal wells in the play, and the study expects about 60-80 rigs could be active in the play by yearend 2008, with most of the drilling in Caddo and DeSoto Parishes in Louisiana.

Woodford

The Devonian-aged Woodford shale lies at 6,000-14,000 ft depths in the Arkoma basin of southeast Oklahoma. The study notes that the $6 million well cost in the Woodford is more than the $2-3/million/well cost in the Fayetteville and Barnett shales.

The study estimates that an 80-acre well in the Woodford will recover about 4 bcf of gas.

Marcellus

The Marcellus shale in the Appalachia basin extends over several states, although most wells drilled to date have been in Pennsylvania, the study notes.

It says Marcellus production has been minimal to date because of the need to expand the existing infrastructure to accommodate the high-pressure gas that the gas transportation system in Appalachia cannot at this time handle.

Most companies have so far drilled mostly vertical wells to delineate the play, but the study expects horizontal wells to be the primary means for developing the formation.

Montney

The Montney shale lies in the east-central part of British Columbia. The study notes that continued drilling should increase production to 1 bcfd by yearend 2009 from the current 600 MMscfd in early 2008.

Operators typical include five to eight fracs/well, and the study expects estimated ultimate gas recovery to increase to 7 bcf/well from the current 5 bcf/well as technology innovation continues.

Horn River basin

The Horn River basin in Northeastern British Columbia extends into the Northwest Territories. The Devonian Muskwa shale is the main play although the basin also has other shales with large original gas in place such as the Fort Simpson, the study says.

Initial well production rates have ranged from 2 to 8.8 MMcfd with wells with more fracs stages producing better, the study notes. The study says estimated ultimate gas recovery ranges from 4 to 6 bcf/section.

Utica

The Utica and the overlying Lorraine shales are relatively new plays in Quebec with only a few wells testing the formations to date. The study estimates that recoverable gas could be as much as 40 tcf (150 bcf/section).

An initial vertical well tested at 1 MMcfd; rates should be higher for horizontal wells with multiple fracs, according to the study.

Emerging plays

Three emerging shale plays listed by the study are Pearsall shales in the Maverick basin of South Texas, the Niobrara shales of Western Colorado, and the Barnett shale in the Delaware basin of West Texas.

The study says the Pearsall is as deep as 3,500 m in places, has a 200-300 m thickness, and contains about 30-175 bcf/section of original gas in place. It notes reports that say initial horizontal wells flowed at 0.8-3.8 MMcfd.

The Niobrara shales outcrop in Kansas and Nebraska, but are at more than 2,500 m depths in western Colorado. The study notes that in the eastern shallower portion of the play, the shales are underpressured and wells have low initial rates, while in the deeper overpressure portion, wells may produced at 1 MMcfd and recover 100-150 bcf of gas/section.

The Barnett in the Delaware basin is twice a deep as the Barnett in the Fort Worth basin and therefore holds much more gas per section. One estimate is that the Delaware Barnett has 500 bcf/section compared with 150 bcf/section in the Fort Worth basin. The study notes that developing Delaware Barnett gas will be more complicated and costly.