Offshore drilling schedules are subject to industry’s use of highly customized subsea trees, which can escalate project costs and delay tree deliveries compared with using standardized equipment.

The International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) promotes standardization of subsea trees and other equipment through its Joint industry Project 33 (JIP 33), supported by the World Economic Forum.

The JIP’s goal is to encourage operators to adopt standardization to cut overall costs and reduce tree delivery times for mulitwell subsea developments. While no single tree design will fit all projects, some companies believe frequent use of standardized tree designs can align manufacturing requirements, improving scheduling efficiencies for most new subsea projects.

Standardization can save 10-20% in cost over the life of a project and reduce equipment lead times by 20-40%, McKinsey Energy Insights said in an analysis commissioned by BP PLC, which chaired JIP 33 Phase 1.

JIP 33 web site documentation notes 75% of large exploration and production projects exceeded budget by 50% on average during 2010-14 while 50% of projects exceeded schedule by almost 40%.

In addition to subsea trees, the JIP is developing standards for the design, construction, and testing of air compressor packages, centrifugal pumps, gate valves, heat exchangers, high-voltage switch gear, pressure vessels, ball valves, and piping material.

Equinor ASA (formerly Statoil) attributed standardized equipment packages for helping lower breakeven on Johan Sverdrup field in the Norwegian North Sea. Project leaders selected standardized equipment over building customized components.

BP reported Thunder Horse field came on stream in the Gulf of Mexico about 15% under budget because the operator and its partners relied on standardized equipment and technology (Fig. 1).

Thunder Horse’s PDQ platform handles production from Thunder Horse North and Thunder Horse South in the Gulf of Mexico. BP said standardized parts helped bring Thunder Horse South on stream Dec. 8, 2016, nearly 1 year ahead of schedule and under budget (Fig. 1). Photo from BP.

IOGP’s JIP 33 “Standardization of Procurement Specifications for Equipment,” is in Phase 2. Participants include BP, Chevron Corp., Eni SPA, ExxonMobil Corp., Petroleo Brasileiro SA, Saudi Aramco, Equinor, Total SA, and Woodside Petroleum Ltd.

The JIP started in 2015 following an IOGP benchmark review and a meeting of oil and gas company chief executive officers in Davos, Switzerland, that year. Phase 2 launched in early July 2017 with Aker Solutions Ltd. providing project management. Chevron is chairing Phase 2, scheduled for completion by Dec. 31, 2018.

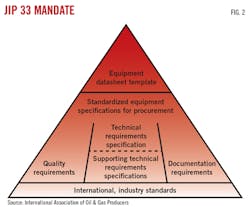

The next phase is expected to focus on standardizing packages such as compressors or pump packages although Phase 3’s scope has yet to be formally defined (Fig. 2).

Well delivery process

Thunder Horse South came on stream Dec. 8, 2016, about 11 months early and $150 million under budget. The extension was completed below budget by relying on proven standardized equipment and technology rather than building customized components.

Thunder Horse involves two fields, North and South, that tap into three main Upper Miocene turbidite sandstone reservoirs.

BP operates Thunderhorse with 75% working interest. ExxonMobil Corp. has 25% interest. A semisubmersible modularized production-drilling-quarters (PDQ) platform is 150 miles southeast of New Orleans on Mississippi Canyon Blocks 778/822.

During construction, BP called the Thunder Horse PDQ the largest platform of its type in the world with quarters for more than 300 people. The 50,000-ton platform sits in more than 6,000 ft of water and has a production capacity of 250,000 b/d of oil and 200 MMcfd of natural gas.

Equinor said earlier this year that it had, together with its partners, reduced Johan Sverdrup Phase 1 development costs by nearly 30% to $11.21 billion compared with the original plan for development and operation (PDO). The project’s breakeven price now is less than $15/bbl.

Equinor is the operator with 40.0267%. Partners are Lundin Norway, 22.6%; Petoro, 17.36%; Aker BP, 11.5733%; and Total, 8.44%.

Johan Sverdrup field involves two discoveries, Avaldsnes and Aldous, offshore Stavanger in 120 m of water. It is one of the largest discoveries made in the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Avaldsnes lies on Production License (PL) 501 while Aldous is part of PL265. The field later was extended into PL502. Appraisal activities showed the two discoveries constitute one giant field.

Project development has benefitted from a drilling and well improvement program, said Margareth Ovrum, Equinor executive vice-president for technology, projects, and drilling.

“We’ve drilled more wells than planned, more than 1 year ahead of plan, which has contributed greatly to cost reductions in the project,” Ovrum said in February. Equinor estimated recoverable resources for Phase 1 at 2.1-3.1 billion boe.

The company expects to submit a Phase 2 PDO by end-2018, with an anticipated cost of less than $5.73 billion, putting overall breakeven for full development at less than $20/bbl.

Project Director Kjetel Digre said, “Standardization of equipment packages, copying of good solutions, and doing things right the first time in collaboration with our suppliers has been critical to the positive developments that we see in the first phase of Johan Sverdrup. In Phase 2 we are taking this one step further, and we are starting to see the results of this.”

Equinor plans to bring Phase 1 on stream in late 2019 and reach 440,000 b/d. Phase 2 is scheduled to start up in 2022. Peak production after the Phase 2 startup is expected to be 660,000 b/d.

Contractors will tie eight wells drilled in 2016 (Fig 3) back to the drilling platform late this year and early in 2019. Drilling from the platform will begin after the tie-backs. As many as 48 wells will be drilled in the first and second development phases.

Eight wells drilled on Johan Sverdrup field will be tied back to the platform by early 2019. Equinor used standardized equipment packages and collaborated with partners during Phase 1, which is scheduled to come on stream in late 2019 (Fig. 3). Photo by Kjetil Eide from Equinor.

Subsea documentation

IOGP reported during a 2014 workshop in Madrid that an average of 466 specifications existed per company per project.

Separately, DNV GL directed an earlier JIP standardization collaboration that resulted in recommended practice (RP) DNVGL RP-0101 regarding technical documentation for engineering, procurement, and construction of subsea projects.

Participants in DNV’s JIP sought minimum paperwork between oil companies, contractors, and suppliers. Martha Viteri, DNV head of subsea and well systems, said replication across the supply chain adds very little, if any, value to the safety or performance of subsea equipment.

Jan Ragnvald Torsvik, Equinor’s lead engineer of life cycle information and JIP co-chair, said Johan Sverdrup project managers implemented a draft RP version to cut waste in handling technical information and help with standardization, efficiency, and quality.

IOGP’s JIP participants note subsea tree standardization requires a cultural shift in industry’s approach because oil and gas companies often are attached to their internally developed standards, which are believed to provide a competitive advantage.

Chris Hawkes, IOGP safety director, said a move away from individual company specifications toward standardization will reduce equipment costs and lead time and help increase reliability.

The more a subsea tree is built to the same specifications, the more companies can learn about potential problems, which will enable equipment manufacturers over time to improve equipment reliability.

Hawkes believes that JIP participants envision eventually having wells and floating production, storage, and offloading vessels constructed to a set of industry standards. This would reduce the time and cost of bringing projects on stream by reducing the engineering work and helping manufacturers deliver components quicker and cheaper.

But Hawkes warns it probably will take years to reach an accepted industry standard for equipment packages. He acknowledges there cannot be a one-size-fits-all tree for installation on every well completion worldwide.

“Clearly, there are differences in reservoirs and fluid composition,” he said. “But there is no reason to have completely different valves or compressors as long as they’re rated for the appropriate conditions and requirements.”

Common architecture

Baker Hughes, a GE company, offers levels of standardization in its completion tools. The most standardized level involves off-the-shelf tools such as packers, liner hangers, flow-control systems, sand-control systems, and valves.

Another standardization level is for “configure to order” tools where about 80% of a tool already is built, leaving frequently customized parts, like threads on a liner hanger, unfinished. The tool is completed based on a customer’s specific order, enabling delivery as soon as finishing touches are made.

BHGE said configure-to-order tools can be delivered up to 65% faster than a highly customized tool.

Schlumberger Ltd. takes what it calls a platform approach to completion equipment, including packers, intelligent completions, safety valves, and isolation valves. Equipment is built using common building blocks that can be modified easily with standard components.

For instance, Schlumberger offers production packer designs in which certain packer components can be customized within an overall common architecture. An operator can select a packer for a well, ordering certain components configured specifically for that well.

Cost reductions

Rystad Energy recently analyzed oil companies’ greenfield project cost performance and concluded that investors can find confidence in BP’s, Eni’s, and Shell’s increased wave of new projects despite the oil price downturn that started in 2014. Matthew Fitzsimmons, Rystad Energy vice-president, said, “The largest difference between the top and bottom performers was engineering, procurement, construction, and installation costs. These costs are most influenced during a project’s design stage.”

For projects that started up since 2014, majors collectively achieved greenfield costs of $13.50/boe. These development costs were in addition to $8.80/boe lifting costs.

Since 2015, BP, Eni, and Shell approved some $64 billion worth of greenfield projects with BP alone approving more than $27.6 billion during the oil-price slump.

Fitzsimmons said BP’s $6 billion investment in Khazzan Phase 1 in Oman achieved greenfield costs below $5/boe. He said the project applied proven gas technologies from a different region, which helped reduce costs.

He calls Royal Dutch Shell PLC’s Malikai project offshore Malaysia another “good example of applying and improving proven technologies in new locations. The company improved its existing tension leg platform pipe design and saved significant development costs.”

The Malikai project shows a clear understanding of holistic-project costs, Fitzsimmons said, adding that increased pipe costs led to cost-reduction efforts on other elements of the project.

“Unfortunately, we’ve seen some operators be ‘penny-wise, pound-foolish,’” in that they saved upfront costs by reducing material quality, which led to significant lifting-cost increases,” he said.

He said oil majors are undertaking fit-for-purpose engineering standardization efforts to improve project executives.

“That is, they have been reviewing engineering specifications and applying critical thinking to eliminate project ‘gold plating,’” Fitzsimmons said.

About the Author

Paula Dittrick

Senior Staff Writer

Paula Dittrick has covered oil and gas from Houston for more than 20 years. Starting in May 2007, she developed a health, safety, and environment beat for Oil & Gas Journal. Dittrick is familiar with the industry’s financial aspects. She also monitors issues associated with carbon sequestration and renewable energy.

Dittrick joined OGJ in February 2001. Previously, she worked for Dow Jones and United Press International. She began writing about oil and gas as UPI’s West Texas bureau chief during the 1980s. She earned a Bachelor’s of Science degree in journalism from the University of Nebraska in 1974.