Gasbol pipeline contract talks focus on pre-salt, regional integration

Dorival Suriano dos Santos Jr.

Research Center for Gas Innovation

Sao Paulo

Edmilson Moutinho dos Santos

University of Sao Paulo

Sao Paulo

Uncertainty regarding the volume of natural gas that can be commercialized from Brazil’s pre-salt has combined with other factors to complicate negotiations on renewing the 20-year contract between Bolivia and Brazil for supplies shipped through the Bolivia-Brazil (Gasbol) pipeline. Bolivia would have to add to its reserves to continue supplying the 16 million cu m/day (mcmd) sent to Brazil. While Brazil, even with anticipated increases in pre-salt production, will likely remain dependent on Gasbol for at least part of its post-2019 supplies.

A combination of huge natural gas reserves in Bolivia and a promising Brazilian consumer market led the two countries to build the 1.1-bcfd Gasbol and place it into service in 1999. Brazil’s natural gas consumption is expected to grow even more over the next two decades, potentially passing oil as the country’s primary fuel source between 2020 and 2030.

Nationalist policies by the Bolivian government, uncertainty regarding new gas reserves in the Andean state, and the approaching end of the purchase-and-sale agreement for gas transported through Gasbol have, however, been leading the Brazilian government to consider supply alternatives that would minimize the risk of supply interruptions to its consumer market, including its own pre-salt basins.

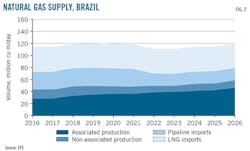

According to the Brazilian Energy Research Office (EPE), natural gas production in the country will increase about 40% between 2017 and 2026, to 60 mcmd from 43 mcmd. Technological innovations could lead to further production increases.

This article describes the main effects and difficulties associated with possibly replacing at least part of the Bolivian gas currently consumed in Brazil with domestically sourced material.

Background

Gasbol begins at Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales Bolivianos’s (YPFB) Rio Grande natural gas plant, 40 km from Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, and runs 3,056 km through six states in Brazil to Petrobras’s Alberto Pasqualini refinery (REFAP), in Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul (Fig. 1).

The supply agreement, signed in 1993, was part of Brazil’s strategy to increase natural gas’s role in its energy mix to 12% by 2012 from 2% in the early 1990s. Natural gas consumption in Brazil grew at an average rate of 12%/year from 1995 to 2000. Contracted volumes of 16 mcmd in 2005 were increased to 30 mcmd in 2007. By the end of 2016, Bolivia supplied 33% of natural gas consumed in Brazil. Besides supplying power plants and refineries, gas imported from Bolivia is delivered to seven local distributors, which together supply 1.2 million consumers.

In addition to its commercial importance for both countries, Gasbol plays a large role in the integration of South America’s energy market. Political leaders from across the ideological spectrum agree that energy integration in South America benefits the region. The contract covering shipments on Gasbol, however, ends in 2019, prompting Brazil to at least consider alternative sources of supply.

Pre-salt gas

According to Brazil’s “10-Year Energy Expansion Plan – 2026,” its domestic gas supplies will grow 37% in the next 10 years, to around 59 mcmd in 2026 from around 43 mcmd in 2017 (Fig. 2), only slightly below EPE’s figures.

Natural gas produced from Brazil’s pre-salt reserves moves to shore via three subsea pipelines:

• Rota 1 (359 km, 20 mcmd) consists of two parts, the Lula field-Mexilhao platform section and the section connecting Mexilhao platform to the Monteiro Lobato gas treatment unit in Caraguatatuba, Sao Paulo, and started service in 2011.

• Rota 2 (401 km, 13 mcmd) which started in 2016, carries 13 mcmd and at 401 km is the longest subsea pipeline operating in Brazil. It connects additional Santos basin production, via an interconnect with Rota 1, to the Cabiunas gas treatment terminal in Macae, Rio de Janeiro.

• Rota 3 (307 km, 21 mcmd) links Lula Norte field to Marica, Rio de Janeiro, with interconnections preinstalled for future production from Atapu, Berbigao, Buzios, Libra, Sepia, and Sururu fields.

Private natural gas distributor Cosan Ltd. has considered developing a fourth pipeline for pre-salt natural gas, connecting the Santos basin to São Paulo state, with a capacity of 15 mcmd. The Cosan line, if built, would supply gas to cities in the Baixada Santista region and elsewhere under the concession of distributor Companhia de Gas de Sao Paulo (Comgas).

Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Energy Economics Group expects total natural gas production in the pre-salt region of the Santos basin by 2025 to increase 87-120 mcmd. Deducting gas that is reinjected, flared, or consumed during exploration and production, however, this number is 28-55 mcmd, roughly equivalent to current Brazilian production.

Even though natural gas reserves in Bolivia have grown since 1998, they may be insufficient to simultaneously meet domestic demand and export commitments to Brazil and Argentina. EPE says some Bolivian fields have already entered final production and new fields have not been discovered to replace production.

Besides uncertainties regarding future production, the 2006 nationalization of the Bolivian oil and gas industry has raised concerns in Brazil regarding potential supply interruptions. Coupled with growth prospects for Brazilian pre-salt production B.razil is now questioning the need for a new 20-year contract.

At the same time, natural gas production potential in the pre-salt basins faces technical and financial troubles. The fields’ distance from the Brazilian shore increases transportation costs. The pre-salt gas also has higher levels of CO2 contamination. Depending on its concentration, the corrosive properties of the extra CO2 can make it impossible to transport the gas, making expensive offshore separation necessary instead.

Such investments would face a consolidated Brazilian downstream market for natural gas. Petrobras, which had a monopoly over the gas industry until 1997, was still as of 2016 responsible for 92% of domestic production and more than 95% of the pipeline network in the country. It also has stakes in 19 of Brazil’s 27 distribution companies and holds 52% of the country’s gas-fired power generation capacity.

These factors have caused the level of reinjected natural gas in Brazilian offshore fields to triple between 2010 and 2016. The volume of pre-salt natural gas that can be commercially used, therefore, is still uncertain.

Other factors

Regardless of developments in Brazilian supply, the energy integration created by Gasbol has been beneficial for both Bolivia and Brazil. It allowed Bolivia to monetize its reserves, increase investments, and expand the scope of its natural gas industry. The gas imported through the pipeline, meanwhile, made it possible for Brazil to develop a consumer market that did not exist.

Bolivia’s economy remains heavily reliant on natural gas. According to data from Bolivia’a Institute of External Commerce, gas made up roughly 50% of the country’s $12.9 million of 2014 exports. To maximize continued benefits for both countries, Sylvie D’Apote, founder and managing partner of the consulting group Prysma E&T Consultores, in an interview for Jornal Valor Econômico, suggested that short or medium-term pipeline agreements should be considered instead of a renewal of the 20-year deal.

Bibliography

Almeida, E., Colomer, M., and Vitto, W., “Gás do Pré-Sal: Oportunidades, Desafios e Perspectivas,” Texto para Discussão IBP, Mar. 17, 2017.

Chavez-Rodriguez, M.F., Garaffa, R., Andrade, G., Cardenas, G., Szklo, A., Lucena, A.F.P., “Can Bolivia Keep Its Role as a Major Natural Gas Exporter in South America?” Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, Vol. 33, July 2016, pp. 717-730.

Economides, M.J. and Wood, D.A., “The State of Natural Gas,” Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering. Vo1. 1, Nos. 1-2, July 2009, pp. 1-13.

EPE, “Plano Decenal de Expansao de Energia – 2026,” July 2017.

EPE, “Plano Decenal de Expansao de Energia – 2024,” July 2015.

Fuser, I., “Conflitos e contratos – A Petrobras, o nacionalismo boliviano e a interdependência do gás natural (2002 – 2010),” post-graduate dissertation, University of Sao Paulo, 2011.

IBCE, “Cifras del Comercio Exterior Boliviano – Gestión 2014,” Santa Cruz, Bolívia, 2015.

Oxilia, V., “Socioeconomic Roots of Energy Integration in South America: Analysis of Itaipu, Gasbol, and Gasandes Projects,” doctoral thesis, University of Sao Paulo, 2009.

Petrobras, “FPSO Cidade de Marica Enters Operation in the Santos Basin Pre-Salt,” Feb. 16, 2016.

Petrobras, “Unidade de Processamento de Gás Natural Boliviano e investimentos no Estado do MS,” August 2013, http://slideplayer.com.br/slide/7295645/.

Rochedo, P., Costa, I., Imperio, M., Hoffman, B., Merschmann, P., Oliveira, C., Szklo, A., Schaeffer, R., “Carbon Capture Potential and Costs in Brazil,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 131, Sept. 10, 2016, pp. 280-295.

Santos, E.M., Gomes, A., Faria, E., Oliveira, H., “Gasoduto Bolivia-Brasil,” Banco Nacional do Desenvolvimento, Infrastructure Projects No. 45, April 2000.

The authors

Dorival Suriano dos Santos Jr. ([email protected]) is a researcher at Brazil’s Research Center for Gas Innovation (RCGI) – Economics and Energy Policy Program and an MS candidate in energy science at the Energy and Environment Institutute, University of Sao Paulo. He has 10 years of experience in the mining and energy industry. Santos holds a BS in chemical engineering from the Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil, where he won the Scientific Initiation Merit Prize at the 6th Brazilian Congress of Chemical Engineering.

Edmilson Moutinho dos Santos ([email protected]) is an associate professor in the graduate energy program at the University of Sao Paulo and co-investigating principal at RCGI’s Economics and Energy Policy Program. He holds an MS in energy systems and policy from the University of Campinas, Brazil, an MS in energy management and policy from the University of Pennsylvania, and a PhD in energy economics from the French Petroleum Institute, Rueil-Malmaison. Santos is former president of both the Brazilian Society of Energy Planning and the Brazilian Association of Energy Studies.