IMO 2020 rules challenge European, Russian refiners—1

Ken Cowell

Tim Bennett

Ramin Lakani

Muse, Stancil & Co.

London

The confirmed reduction in sulfur content for marine bunker fuel to 0.5 wt % by Jan. 1, 2020, from a current 3.5 wt % by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) will hugely impact the refining industry’s ability to timely supply the required volume of low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO) and dispose of surplus high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO) that will no longer be saleable as marine bunker fuel. IMO is the United Nations agency that organizes the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).

While this change will affect refining operations worldwide, the new IMO regulations will acutely impact European and Russian refiners, which have large surpluses of HSFO that need to be placed elsewhere in the market. If the refineries producing HSFO don’t find a new outlet for it and cannot effectively blend or convert it, their future economic viability will become questionable.

Part 1 of this two-part article, presented here, examines challenges faced by European and Russian refineries and begins a discussion of potential mitigation plans under consideration by the affected industries and businesses ahead of the 2020 deadline.

Interdependent issues

An interdependency exists between refining and shipping industries; shippers rely on supply of heavy fuel oil (HFO) and marine diesel-gas oil from refineries, while refiners rely on shippers as an outlet for a large portion of their HSFO.

To put this into perspective, global HFO production in recent years has exceeded 400 million tonnes/year, with close to 47% of HFO production ultimately consumed as marine bunker fuel. As electricity generators move away from burning HSFO and switch to natural gas, the importance of the shipping industry increases even more for refiners. Because of the IMO changes:

• Refiners need to find a way to dispose of the HSFO they currently produce. The obvious solution is to blend it with lower-sulfur distillates to meet the 0.5 wt % limit, but this route poses additional difficulties to be discussed further in this article. Another disposal method would be to use a coker to process HSFO further, which would require large capital investments for refineries without the existing processing equipment to do so.

• Some refiners may switch to lower-sulfur crudes to meet the fuel oil sulfur limits. Most Russian refineries, however, are constrained to use Urals crude and will not have the option to switch to sweeter crudes. The price of sweet crudes is also likely to rise, creating unfavorable refinery economics.

• Shipowners of close to 70,000 vessels possibly affected must decide whether to switch to low-sulfur marine gas oil (LSFO, MGO) from HSFO, change fuel type to LNG, or install scrubbers to reduce exhaust emissions. Each of these options presents both problems and opportunities for associated industries such as scrubber manufacturers (who are working at full capacity to meet the demand) and port operators (who are evaluating the potential for storing LNG but still are unsure about how quickly the industry will adopt the fuel).

• The industry expects distillate or distillate-based LSFO to become the most sought-after fuel choice for ships, but unanswered questions remain regarding price, availability, and compatibility of such blends. Several large bunker-fuel marketing companies have warned about the ability of new blends to meet quality requirements for ship engines.

Regulatory background

Initiated in 2005 with a further revision in 2008, the IMO MARPOL Annex VI Protocol marine fuel oil sulfur-reduction program aims to improve air quality and reduce impacts of harmful emissions on human health by progressively reducing atmospheric emissions from ships. Specifically, reductions in sulfur-oxide emissions resulting from the reduced fuel-sulfur content will reduce production of sulfur-nitrogen compound particulates that cause or exacerbate lung diseases and related illnesses.

The IMO’s change to 0.5 wt % sulfur has caused difficulties for refiners due to the organization’s initial lack of clarity on the schedule for this change. When the regulation was first proposed in 2008, the target implementation date was stated as Jan. 1, 2020, but with a possible delay to as late as 2025, depending on an assessment—to be undertaken by 2018—of the likely availability of compliant fuel.

Most refiners were reluctant to commit to large investments in residue conversion projects for startup by 2020 when the benefits of such projects may not be realized for a further 5 years. The IMO implemented its review of likely compliant fuel availability in 2016, with a decision made in October 2016 to confirm the January 2020 implementation date. This decision came as a surprise to many refiners and shipowners, who had expected implementation to be delayed until 2025 and faced insufficient timescale to build new residue conversion capacity to reduce or eliminate HSFO production, projects which have a 4 to 5-year decision-to-startup cycle.

A further amendment to the Protocol is currently under discussion by IMO members to aid policing and compliance to the new global specifications. This amendment would ban the storage of HSFO on board vessels (except for tankers where the HSFO is a cargo) from April 2020.

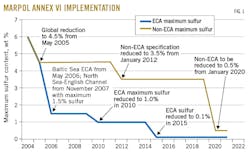

Fig. 1 shows the sequence of changes adopted by the IMO, including the establishment of emission control areas (ECAs).

Currently, there are four ECAs: the Baltic Sea, North Sea, North American US-Canada, and US Caribbean.

Scale of HSFO-disposal problem

IMO will apply the regulation reducing maximum-sulfur content in marine bunker fuel to 0.5 wt % globally. Inside ECAs this limit is already reduced to 0.1 wt %. The regulation change, however, will pose a problem for European and Russian refiners because of the relatively high yield of HFO produced by European and Russian refineries compared to the refining sector in other developed countries and the high proportion of European and Russian HFO production currently consumed as marine bunker fuel.

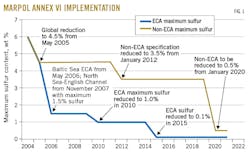

Fig. 2 compares the average HFO yield for 2016 for the refining industries in the US, Canada, South Korea, Japan, OECD Europe, and Russia.

The HFO yield for the US and Canadian refining industries is low due to the large amount of residue upgrading capacity in place at many refineries, particularly delayed cokers. This low-HFO yield is achieved despite some US refiners running large volumes of heavy Canadian, Mexican, and Venezuelan crudes. The increasing volumes of light tight oil (LTO) from shale operations will further reduce both the amount of sulfur that North American refineries need to treat and their fuel oil yields.

Refineries in South Korea and Japan have on average somewhat higher HFO yields than the North American refining sector but have relatively strong inland demand for HFO: 59% and 77% of their refinery HFO production consumed inland, respectively, in 2016.

The European refining sector in 2016 had an average HFO yield of 11.4 wt % on refinery input, reflecting the relatively small coking and residue hydroprocessing capacity in place in European refineries compared to North America. A small number of new residue upgrading projects are due to be completed and commissioned in European refineries before January 2020, reducing European HFO yield by an estimated 4-5 million tpy to under 10% of refinery input.

The HFO yield for the Russian refinery sector has declined for the past 5 years due to commissioning of upgrading projects at several refineries but remains high even by comparison to the European refiners. Average Russian refinery HFO yield in 2013 was almost 28 wt %, declining to a slightly more than 18 wt % in 2017 based on preliminary industry data. Historically, many Russian refineries had a relatively simple hydroskimming configuration, resulting in atmospheric residue exported notionally as HFO, with some of this material also purchased by European and North American refiners as a feedstock. The Russian refinery upgrade projects completed in recent years and currently under construction are mainly vacuum distillation and FCC-hydrocracker projects, which—while reducing HFO production by cracking vacuum gas oil (VGO) to more valuable, lighter products—don’t eliminate HSFO production completely. Only a small number of residue cracking-coking projects have been built or are currently planned in the Former Soviet Union (FSU).

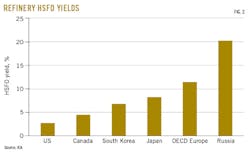

Fig. 3 shows European and Russian HFO production, notional disposition of that HFO production as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA), and Muse estimates of the final use of that production.

Total HFO production in OECD Europe and the FSU in 2016 was about 145 million tonnes, split roughly evenly between the two regions. Inland consumption for power generation and industrial-heating use is a relatively small proportion of total production in both regions, at about 16.5 million tonnes in OECD Europe and 9 million tonnes in the FSU.

Most of the inland HFO consumed in Europe meets the 1 wt % maximum-sulfur content required by the European Union Large Combustion Plant Directive. Some HSFO is burned at power plants with flue gas scrubbers. HFO consumption for power generation in the FSU is relatively small due to the ready availability of low-cost natural gas and coal. A large volume of HSFO is sold as marine bunker fuel at European and FSU ports, particularly in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp (ARA) region.

In 2016, OECD Europe’s HFO marine bunker sales were almost 34 million tonnes, with FSU sales more than 5 million tonnes.

Surplus HFO production not consumed in the inland market or sold as marine bunker fuel in European-FSU ports must be exported. Overall HFO exports from OECD Europe and the FSU in 2016 totaled more than 70 million tonnes.

HFO disposition data as reported by the IEA understate the dependence of the European and FSU refining sectors on marine bunker fuel sales as an outlet for surplus HSFO. While IEA data identify around 40 million tpy of HFO sold as marine bunker fuel in European and FSU ports, the data don’t readily show how 70 million+ tpy of HFO exports are ultimately consumed. IEA provides detailed data for export destinations for OECD Europe but not for Russia-FSU. Muse has analyzed available data on final disposition of the export volumes and estimates that about 45 million tpy is ultimately sold and consumed as marine bunker fuel in other regions:

• In 2016, more than 15 million tonnes of HFO was exported from OECD Europe to Asia Pacific, primarily to Singapore. About 85-90% of Singapore HFO imports and production are consumed in the local marine bunkering market.

• About 3 million tonnes was exported to the Middle East for marine bunker fuel blending at Fujairah, UAE, a major marine bunkering location.

• Almost 6 million tonnes was reported as exported to non-OECD Europe-Eurasia. Most of this material was used as marine fuel in bunkering centers such as Gibraltar and Malta.

• About 6 million tonnes was reported as exported to African destinations. Analysis of Africa’s historical HFO consumption suggests a large part of this volume was consumed as marine fuel oil.

Overall, Muse estimates that, out of the 145 million tonnes of HFO produced in 2016 by OECD Europe and Russian-FSU refining industries, about 86 million tonnes (roughly 59%) was consumed as marine bunker fuel, highlighting the scale of potential disruption for these refineries.

Meeting 2020 IMO regulations

Ship owners have three main options to meet the requirements of the 2020 IMO bunker fuel sulfur emission regulations:

• Fitting flue gas scrubbers to remove sulfur oxides, while continuing to burn HSFO.

• Switching to using LNG as a marine fuel.

• Buying 0.5 wt.% sulfur fuel oil or MGO distillate fuel.

While details of these options will be addressed in Part 2 of this two-part article, suffice it to say that the extent to which each of these options is adopted by the shipping industry has an impact on the response of refiners, adding to refining-sector uncertainty.

Muse believes that most existing vessels will look to comply with the IMO regulation from January 2020 by switching to LSFO or distillate fuel with a sulfur content of 0.5 wt % or less, presenting the European and Russian refining industries with two questions: how can sufficient 0.5 wt % sulfur marine fuel oil be produced to meet the shipping market demand in European and FSU ports? And what will be the alternative disposition for HSFO currently sold as marine bunker fuel?

Major oil companies have been researching options to produce some amount of compliant bunker fuel through segregation and blending of low-sulfur heavy distillate and residue streams. Different refineries will use different component blends of cracked and straight-run material to produce compliant marine bunker fuel, raising issues of compatibility between marine bunker fuel batches supplied from different sources.

It is likely that much of the demand for 0.5 wt % sulfur bunker fuel will be met by shipowners switching to MGO, which will require an increase in distillate imports into Europe from other regions. Blending LSFO bunker fuel with low-sulfur distillate and substituting HSFO bunkers with MGO will result in rejection of high-sulfur residue streams from the marine bunker fuel blending pool.

The positions of the European and Russian-FSU refining industries in terms of potential solutions to the bunker fuel problem differ. The European refinery fleet is at a mix of inland and coastal sites. The inland refineries generally produce a relatively low yield of HSFO, most of which has less than 1.0 wt % sulfur and is mainly consumed in local markets. This is achieved by refiners selecting a low-sulfur crude slate, having residue upgrading-destruction capacity, or a combination.

European coastal refineries can process a wide range of seaborne crudes and are currently able to dispose of surplus HSFO via export to distant markets. Some European coastal refineries have residue conversion installations, produce little HSFO, and, therefore won’t be greatly impacted by the 2020 marine bunker fuel sulfur specification change. Other coastal refineries without residue upgrading and higher HFO yields, however, have the technical option to switch their crude slate to very low-sulfur crudes to produce HFO compliant with the IMO regulations.

Given market expectations that the sweet-sour crude oil price spread will widen amid increased demand for low-sulfur crudes, those refineries with residue upgrading capability that can continue to process more sour crudes (and thereby penalize those refineries that must switch to a very low-sulfur crude slate) will benefit. The ability of refiners to change to a low-sulfur crude slate, however, also is limited by the availability of suitable crude oils.

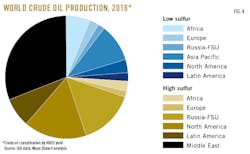

Fig. 4 shows global crude oil production data for 2016, with Muse’s estimated breakdown by region and sulfur content.

For the purposes of its analysis, Muse classified crude oils as low-sulfur if a 0.5 wt %-sulfur HFO could be produced by blending the vacuum residue with a low-sulfur distillate blend stock, with the distillate comprising less than 35.0 wt % of the blend. Based on this analysis, only 26% of crude oil produced globally meets the criteria for the low-sulfur classification. Some of these crudes will not be readily available to European refiners since they are already sold into markets where a low-sulfur content is a key parameter.

For example, most crude oils produced in the Asia Pacific are consumed within the region, either in the producing country’s own refining system or at nearby refineries to produce low-sulfur fuels compliant with national regulations for onshore use, including an HFO sulfur limit. Much of US LTO also is processed at inland refineries and is not available for export, while China is a competitive buyer for many West African crudes.

Conversely, in some regions that are generally considered low-sulfur crude producers (e.g., the North Sea), a large proportion of production has a vacuum-residue sulfur content well exceeding 1.0 wt % (e.g., Forties, at typically around 2.5 wt %).

The Russian refining industry has limited options in terms of changing crude slate to reduce HFO sulfur content. Almost all major refineries in Russia are at inland locations and run Urals crude oil supplied by pipelines. HFO produced from Urals crude processing typically has a sulfur content of about 2.5 wt %. It would be technically impractical and economically unviable to change to a low-sulfur crude slate for almost all of Russia’s refineries, and coker or residue hydrocracking-hydrotreating projects that would be required to convert or destroy HSFO produced by Russian refineries take 4-5 years to install. Projects not currently at an advanced stage of construction will not be commissioned before January 2020.

After the change in marine bunker fuel specifications on Jan. 1, 2020, most Russian refineries will rely on selling their HSFO into the limited market for vessels fitted with scrubbers that can still use it or into export markets for onshore consumption, where environmental regulations allow burning HSFO.

Alternative outlets will need to be found for surplus HSFO displaced from the marine bunker fuel market. There will be potential to increase onshore HSFO consumption for power generation if HSFO prices fall to an energy cost at parity with coal and natural gas. In the short to medium term, however, the volume of increased power plant consumption will be limited to increasing utilization rates for existing oil-fired power plants (for peak loading) since power companies will be unlikely to build new oil-fired plants for economic and environmental reasons, and certainly not by 2020. In some of the developed economies (e.g., the UK), oil-fired power plants were deemed uneconomic and shuttered in the 1980s and 1990s and are no longer available for operation.

As mentioned earlier in this article, on average, US refineries, particularly those at the US Gulf Coast (USGC) are more complex than European and Russian refineries, with many having delayed coking or other residue upgrading processes. US refiners already import VGO and atmospheric residue feedstocks to fill spare capacity in their upgrading units. Increasing use of LTO in USGC refineries will tend to underload coking capacity, providing an opportunity for US refiners to buy surplus low-cost HSFO from Europe and the FSU as supplementary coker and residue hydrotreater-hydrocracker feedstock.

Many Russian refineries will need to invest in residue conversion capacity to eliminate HSFO production or face closure due to the decline in HSFO market volume. The extent of this investment will depend on choices by shipowners (in terms of installation of exhaust gas scrubbers and use of LNG as a fuel) and the volume of HSFO complex US refineries can process as supplementary feedstock.

Ongoing concerns

In recent years, refiners have succeeded in facing many events involving adapting operations and investing in new installations to comply with environmental and health-driven changes in product quality, particularly with respect to reducing sulfur content of automotive fuels. Most of these changes, however, were implemented on a regional basis, providing refiners with the option of exporting noncompliant production to regions with less stringent specifications, at least for a transitional period. The IMO marine bunker fuel specification change to 0.5 wt % sulfur is different given that the change is global and affects both the shipping and refining industries simultaneously.

The investment options for refiners to convert-destroy HSFO are effectively an order of magnitude more expensive and complex than those implemented to produce low-sulfur gasoline and distillate fuels. Uncertainty over the number of vessels that will fit scrubbers or switch to LNG as a fuel, as well as the timing of these changes, adds to the uncertainty for refiners in terms of the size of the remaining HSFO market and the overall demand for marine fuel oil and MGO in the future.

An added complexity is the direct interaction between the refining, shipping, and port industries that needs to be managed. The relatively short time-limit on industries that traditionally work on 5 to 10-year investment cycles is a further concern.

Part 2 of this article will address potential mitigation plans for both the refining and shipping industries.

The authors

Ken Cowell ([email protected]) serves as managing consultant at Muse, Stancil & Co., London, where, since 1996, he has completed technical and valuation assignments for various midstream and downstream assets in Europe, the Former Soviet Union, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific regions. Before joining Muse, Cowell worked for BP PLC and Mobil Oil Co. Ltd. for more than 20 years in a wide range of refinery operations, technical, supply, distribution, and trading positions. He holds a BS in chemical engineering.

Tim Bennett ([email protected]) is a principal consultant at Muse, Stancil & Co.’s London office, where he has worked for more than 20 years and completed a wide range of consulting assignments in the oil and gas sector in Europe, the Former Soviet Union, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific regions. With more than 37 years’ industry experience, he previously worked for Mobil Oil Co. Ltd. and M.W. Kellogg Co. Bennett holds a BS (1980) in chemical engineering from Loughborough University, UK.

Ramin Lakani ([email protected]) is an energy industry advisor at Muse, Stancil & Co., London. With more than 28 years’ experience in upstream, midstream, and downstream projects, Lakani previously worked for Esso Petroleum, Premier Oil PLC, BG Group, Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Schlumberger Ltd., Petro-Canada, Gaffney, Cline & Associates, and Halliburton Co. and has worked closely with both national and international oil companies to develop their assets. A Chartered Engineer, he holds a BS (1990) in chemical engineering from University College London and an MS (1994) in petroleum engineering from Imperial College London.