US LNG exports set for rapid expansion

Michael C. Lynch

Energy Policy Research Foundation

Washington, DC

Although most forecasts for natural gas consumption and LNG trade foresee modest growth, and even decline due to climate change policies, the more likely case is that cheaper, more flexible LNG supplies—especially from the US—will experience rapid growth. Competing with cheap coal in India or Russian gas in Europe might prove difficult, but a combination of changes in technology and the growth of infrastructure will make imports of LNG much more attractive to a broader range of customers, from shipping operators to coastal power plants.

Long-term price forecasting has proven difficult, to say the least, but the International Energy Agency (IEA) and many others expect that oil and natural gas prices will increase over the long term, except for US natural gas, making US LNG exports ever-more attractive. Even if these forecasts prove too optimistic, the competitive spirit of US exporters should enable them to exploit larger and larger niche markets.

Background

In the first few decades of the LNG business, stability was the norm and in many ways the business was very low risk. Suppliers didn’t initiate investments until they had sales locked in (usually 20-years worth) and customers didn’t sign contracts until enough reserves had been proved to meet them. Although prices were not guaranteed, by being linked to oil prices they were almost always high enough to allow producers to make a profit, sometimes a handsome one. Competition with coal or pipeline gas was typically limited, especially in Asia, and gas’ market share in importing nations was typically low enough that there was little demand risk.

Now, the world is turned upside down. After crashing early last year to below $3/MMbtu, prices for spot cargoes have soared to as high as $30/MMbtu in Asia and projects that had been struggling due to weak demand are now flourishing despite the pandemic. Interest in new export projects has heightened, including in the Eastern Mediterranean (where pipelines could be used instead), East Africa, and for additional plants in Russia and the US.

The evolution of the LNG business is profound and its future will look very different from its past, with significant uncertainty as to the paths producers will take in their business plans. There are, however, certain developments that are suggestive of the industry’s future.

Transformation

Several major changes have occurred in the LNG business over the past two decades, accelerating in recent years. First, as mentioned, the increasingly mercantile nature of the busines, shifting from a regulated, oligopolistic market to something closer to a commodity market with a large amount of spot sales, merchant producers, and price volatility. Demand risk has increased significantly in the past few years as well.

As recently as 2000, five importing countries made up 87% of the market and five producing countries supplied 78% of the material being sold. In 2019, the top five importers made up only 62% while the top five exporters made up 69%. But the exporters now include Australia and the US, in which a wide variety of individual companies with minimal state control are the actual sellers. Sales from these companies increased to 33% of the export market in 2019 from 9% of exports in 2000.

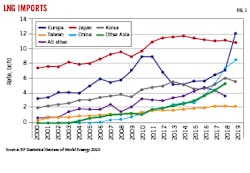

The availability of huge stranded natural gas reserves (those without nearby customers), combined with an increasing number of countries in which wealth and environmental concerns have grown, have significantly expanded LNG trade. The market had previously been dominated by Asian nations without access to pipeline gas. In 2000, 72% of LNG was imported by just three countries: Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. By 2018, their share had dropped to 45% and there was much more gas-on-gas competition, especially in Europe (Fig. 1).

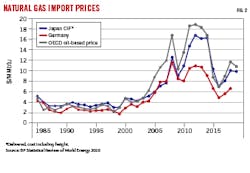

The three Asian countries had no competing sources of supply and were in effect facing an oligopolistic market, in which prices were almost always well above the cost of production, liquefaction, and transport. This is part of the reason Asian prices were traditionally above European prices (Fig. 2). Japanese prices were often about 30% above German prices until 2011, when the Fukushima incident resulted in a shutdown of the country’s nuclear power plants and a scramble for alternative fuel supplies. The LNG market being relatively inflexible, prices soared but the increase was transient (Oil & Gas Journal, Mar. 4, 2013).

Pandemic’s demand impact

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has suggested to some that energy demand, and especially demand for fossil fuels, will be depressed over the long-term because of a combination of weaker economic growth, behavioral changes by consumers, and renewed attention to the threat of climate change. All of these are possible, but the arguments should be considered carefully.

Post-pandemic stimulus packages could mean that economic growth is not significantly weakened and there may in fact be a rebound effect, as is often seen from recessions. In countries like China where the pandemic was brought under control, most people reverted to pre-pandemic behavior, rather than working and shopping from home. And while climate change might receive extra attention as the next crisis demanding urgent action, and infrastructure spending could boost investment in renewable power, it is also possible that pandemic-derived debt overload will mean less spending on expensive renewables.1

The pandemic has affected demand for natural gas much less than for oil: reduced commuting and travel actually has increased demand for residential energy. US energy consumption through October 2020 was down year-on-year by 7.5%, but natural gas consumption only dropped 1%, according to US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. And any boost in spending on renewable energy will mean at least some years of growing demand for natural gas to power back-up generators.

It should also be emphasized that forecasters have a habit of projecting short-term, transient events into the distant future. Many argued that the 1979 oil price spike was due not to the disruption of oil supply from Iran, but rather the simple insufficiency of oil resources, and that prices would continue rising.2 The 1998 oil price collapse was thought by some to represent a lasting glut rather than a temporary price war between Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.3 Many of the same people promulgating this theory backtracked when oil prices spiked in 2008.

At this stage, it is all but impossible to predict whether economic growth will rebound and people will return to pre-pandemic levels of commuting and in-person shopping, as well as whether spending on renewables will affect global natural gas demand, but at the very least skepticism regarding arguments that the world has permanently changed is warranted.

Potential LNG boom

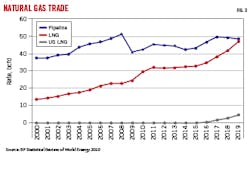

LNG trade has soared in the past decade, to the point where volumes are roughly the same as pipeline gas exports (Fig. 3). The development of floating storage and regasification units (FSRU), which allow supplies to be delivered to areas without large-scale regasification terminals, has greatly expanded the market.

Natural gas’s role in the global economy has been boosted by two factors: its cleanliness and its utility in power plants, especially gas turbines, which have high efficiency and are very flexible. As such, natural gas is often the preferred fossil fuel for power generation and ideal for providing backup to renewable power supply (wind and solar) which are inherently variable and unpredictable. Even forecasts that predict a near-term peak in oil demand foresee a continuing role for natural gas, at least for well after the oil peak. For example, DNV GL’s 2020 forecast predicts that oil demand peaked in 2019, but that natural gas demand, after overtaking oil in 2026, will not peak until 2035.4

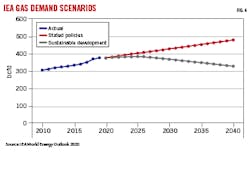

The role of natural gas in combatting climate change becomes readily apparent when considering the US shale revolution, in which switching from coal to natural gas in power generation has greatly outweighed the rise in renewables in reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Even so, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that in a sustainable development scenario, which implies compliance with the Paris Accords, natural gas use will begin declining soon (Fig. 4), but only by 15% through 2040, versus nearly twice that decline in oil use.

New markets

The twin problems of climate change and energy poverty suggest room for a significant expansion of natural gas markets in general. The world still uses approximately 5.5 billion tonnes of coal/year, which produces the most GHG/btu, along with numerous other pollutants. There are 770 million people without access to electricity and 2.6 billion people without access to clean cooking.5 Even aside from the problem of global warming, pollution from coal is a major factor in premature deaths, with the World Health Organization estimating that 4.2 million such deaths occur annually from outdoor pollution, although the breakout for coal is not given.6

More specifically, different markets are attractive for different reasons. Although there is likely to be slow growth in existing LNG markets, namely utilities in Europe and Asia, a major expansion can be expected to occur in five areas:

- Competing with pipeline gas, especially in Europe but increasingly elsewhere.

- Competing with cheap coal in countries like China and India.

- Meeting peaking demand due to seasonal swings in the need for heating and cooling.

- Displacing bunker fuels in large vessels and equipment.

- Providing small markets with power, particularly in the southern hemisphere and initially along the coastlines.

As was shown in Fig. 2, gas prices are lower in areas like Western Europe where the primary competition is not oil but pipeline gas. Although pipeline gas is, by definition, fixed in its location it nonetheless is very successful at providing reliable supply at relatively low cost. The oligopolistic nature of gas supply to Europe, dominated by Algeria, Norway, and Russia, has kept prices well above marginal costs, allowing producers leeway to undercut imports of LNG and prevent larger market penetration. Granted, some countries seek diversity of supply, especially in Eastern Europe, but the amount they are willing to pay above market prices is undoubtedly limited, making this one of the more difficult markets to penetrate.

The potential for massive increases in natural gas use is clear given the need to reduce coal consumption. A quarter of the world’s energy use is still met by coal, which creates substantial local pollution as well as contributing to global warming. Unfortunately, the low price of coal especially in China and India, which comprise more than 60% of the world’s coal consumption, will make it difficult to penetrate these markets as well.

As Table 1 shows, expectations are for coal prices to remain low over the next 20 years, and it will be difficult for US LNG to compete on the basis of commodity price alone. Carbon taxes in OECD countries would significantly increase the competitiveness of LNG but are less likely to be imposed in non-OECD countries such as India. Still, Chinese efforts to reduce local pollution will increase demand for LNG in that market. The remaining coal use still amounts to nearly 50 tcf of natural gas equivalent, about one-third the current global gas consumption, and even minor displacement of this coal will greatly increase LNG demand.

The implementation of the IMO 2020 restrictions on ship emissions has encouraged development of LNG-fueled vessels which, in the US especially, are very attractive economically because of low natural gas prices. At present, most of the market is restricted to local shipping such as ferries and cruise lines, since LNG fueling stations are not widespread, but as infrastructure develops, and especially as FSRU come into widespread use, this market should become sizable. Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates there could be as much as 500 bcf/yr of demand for bunkering LNG by 2025, for example, and demand should accelerate as availability of LNG in more ports grows.7

The relatively recent development of FSRU has opened a major new market, as they have a number of advantages over conventional regasification terminals. For example, site preparation is minimal. Excelerate Energy estimates that an FSRU can be developed in 1-3 years, versus 4-6 for an on-land regasification terminal. There is obviously much less risk of local opposition to siting an FSRU than an onshore plant, reducing political risk.

At present, there are only about 40 operating, but as the number grows it will be possible to buy an idle unit rather than building from scratch.8 Combined with barge-loaded power plants, coastal cities with no access to pipeline gas will be able to acquire power generation in a short period of time, and at competitive prices with most other sources. The market potential is enormous and could fuel LNG demand growth for many years to come.

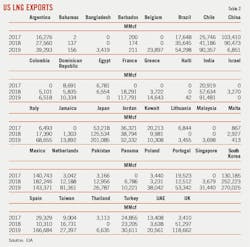

The 1996 founding of Cheniere Energy, the first merchant LNG company, seemed a small tremor at the time, but has generated massive change in the industry; most notably, when it became an LNG exporter rather than importer. American LNG producers have taken a completely different approach to the market than their competitors who, as mentioned, relied almost entirely on long-term contracts and point-to-point sales at oil-indexed prices. US companies, by being willing to price their LNG on a cost-plus basis have been able to compete more effectively with oil, pipeline gas, and even sometimes coal. As Table 2 shows, sales have fluctuated wildly and often include small volumes to niche markets, including barge delivery in the Caribbean.

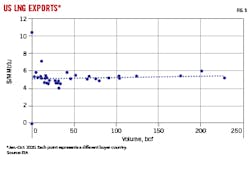

US exporters also have been much more willing to make spot or short-term trades, which have gone from minimal amounts in the early decades of the LNG business to about one-third of transactions now.9 Although this meant sales from the US cratered last year when the pandemic and a warm 2019-20 winter left markets oversupplied, the recent cold weather has prompted much higher spot prices of which US exporters can take advantage. Still, as Fig. 5 shows, a significant amount of US LNG sales last year were to small buyers.

References

- Sandrea, I. and Lynch, M.C., “The Pandemic, Peak Oil Demand, and the Oil Industry,” EPRINC, Feb. 11, 2021.

- Lynch, M.C., “The Peak Oil Scare and the Coming Oil Flood,” 2016, Prager Publishers, Santa Barbara, Calif.

- “Drowning in Oil,” The Economist, Mar. 6, 1999.

- DNV-GL, “Energy Transition Outlook 2020: A Global and Regional Forecast to 2050,” Hovik, Norway.

- International Energy Agency, “World Energy Outlook 2020,” p. 40.

- World Health Organization, “Outdoor (Ambient) Air Pollution,” May 2, 2018.

- International Gas Union, “Global Gas Report 2020,” p. 22.

- McCaul, J., “FLNG and FSRU Market Outlook,” Offshore Engineer, Vol. 44, No. 1, January-February 2019, pp. 17-20.

- International Gas Union, “Global Gas Report 2020,” p. 17.

The author

Michael Lynch is a Distinguished Fellow with the Energy Policy Research Foundation in Washington, DC, and president of Strategic Energy & Economic Research. He has worked on energy economics and policy for over 40 years, much of it at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (from which he also received multiple degrees), is published in seven languages, and is the author of 2016’s “The Peak Oil Scare and the Coming Oil Flood.” He serves on the editorial board of several publications, including Oil & Gas Journal, and is a senior contributor for Forbes.