Natural gas pipeline operators’ net incomes jump 68%

Natural gas pipeline operators’ revenues and net incomes both surged in 2018. Revenues were up for a second straight year, while profits jumped nearly 68% to reach an all-time high in excess of $10.5 billion. Additions to gas pipeline operators’ systems nearly doubled from 2017, with activity buoyed by lower estimated pipeline construction costs.

US oil pipeline operators’ revenues and profits were both also up, but trailed the strength seen in the natural gas segment. Net incomes increased more than 19%. Revenues rose for the thirteenth time in as many years, up more than 14% from 2017.

Details

The rise in oil pipeline profits as compared with revenues caused earnings as a percent of revenue climb to nearly 57%. The spike in natural gas pipeline operators’ net incomes meanwhile moved earnings (Fig. 1) as a share of revenue up more than 12.5 percentage points to roughly 38.6%.

Proposed new-build natural gas mileage was down from 2018’s announced build, despite the lower construction costs. Compression costs dropped by nearly 22% and planned horsepower additions were strong and steady, approaching 300,000 hp.

Dramatic decreases in all land pipeline construction cost areas except right-of-way combined for overall costs less than half of what was estimated in 2018. Miscellaneous costs plunged to $1.3 million/mile from $4.2 million/mile, while estimated labor costs dropped to $2.2 million/mile from $4 million. Material costs fell by almost 50% to roughly $700,000/mile. The $5.3-million decrease in total estimated $/mile land pipeline construction costs moved them to $4.6 million per mile, 54% less than 2017.

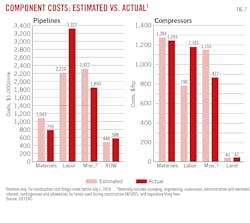

Actual land pipeline construction costs for projects completed in the 12 months ending June 30, 2019, were roughly $500,000/mile (8%) more than estimated costs. Labor costs alone were more than $1 million/mile more than estimates, more than making up for lower material and miscellaneous expenses. Actual compressor station costs were just 2.5% more than estimated costs for projects completed by June 30, 2019.

US pipeline data

At the end of this article, two large tables (beginning on p. 54) offer a variety of data for US oil and gas pipeline companies: revenue, income, volumes transported, miles operated, and investments in physical plants. These data are gathered from annual reports filed with FERC by regulated oil and natural gas pipeline companies for the previous calendar year.

Data are also gathered from periodic filings with FERC by those regulated natural gas pipeline companies seeking FERC approval to expand capacity. OGJ keeps a record of these filings for each 12-month period ending June 30.

Combined, these data allow an analysis of the US regulated interstate pipeline system.- Annual reports. Companies that FERC classifies as involved in the interstate movement of oil or natural gas for a fee are jurisdictional to FERC, must apply to FERC for approval of transportation rates, and therefore must file a FERC annual report: Form 2 or 2A, respectively, for major or nonmajor natural gas pipelines; Form 6 for oil (crude or product) pipelines.

The distinction between “major” and “nonmajor” is defined by FERC and appears as a note at the end of the table listing all FERC-regulated natural gas pipeline companies for 2018 at the end of this article.

The deadline to file these reports each year is in April. For a variety of reasons, companies often miss that deadline and apply for extensions, but eventually file an annual report. That deadline and the numerous delayed filings explain why publication of this OGJ report on pipeline economics occurs later in each year. Earlier publication would exclude many companies’ information.

- Periodic reports. When a FERC-regulated natural gas pipeline company wants to modify its system, it must apply for a “certificate of public convenience and necessity.” This filing must explain in detail the planned construction, justify it, and––except in certain instances—specify what the company estimates construction will cost.

Not all applications are approved. Not all that are approved are built. But, assuming a company receives its certificate and builds its facilities, it must—again, with some exceptions—report back to FERC how its original cost estimates compared with what it spent.

OGJ monitors these filings from July 1 to June 30 each year, collecting them, and analyzing their numbers.

Reporting changes

The number of companies required to file annual reports with FERC may change from year-to-year, with some companies becoming jurisdictional, others nonjurisdictional, and still others merging or being consolidated out of existence. Such changes require care be taken in comparing annual US petroleum and natural gas pipeline statistics.

Only major gas pipelines are required to file miles operated in a given year. The other companies may indicate miles operated but are not specifically required to do so.

Reports for 2018 show an increase in FERC-defined major gas pipeline companies: 100 companies of 180 filing, from 93 of 166 for 2017.

The FERC made a change to reporting requirements in 1995 for both crude oil and petroleum products pipelines. Exempt from requirements to prepare and file a Form 6 were those pipelines with operating revenues at or less than $350,000 for each of the 3 preceding calendar years. These companies must now file only an “Annual Cost of Service Based Analysis Schedule,” which provides only total annual cost of service, actual operating revenues, and total throughput in both deliveries and barrel-miles.

In 1996 major natural gas pipeline companies were no longer required to report miles of gathering and storage systems separately from transmission. Thus, total miles operated for gas pipelines consist almost entirely of transmission mileage.

FERC-regulated major natural gas pipeline mileage grew in 2018 (Table 1), final data showing a rise of 2,409 miles, or 1.29%. Growth in oil mileage was even stronger, 2,923 additional regulated miles marking a 1.76% increase.

Rankings; activity

Natural gas pipeline companies in 2018 saw operating revenues rise by more than $4 billion or roughly 17% from 2017, reversing a large part of the previous year’s declines. Net incomes spiked nearly $4.3 billion (68%).

Oil pipeline earnings also jumped, rising by $2.7 billion (19%), the third consecutive year of net income growth at least that high following a sharp decline in 2015. Revenues rose $3.6 billion or 14% (Table 2).

Crude deliveries for 2018 increased by nearly 1.8 billion bbl or 16%, while product deliveries rose more than 650 million bbl (8.2%).

OGJ uses the FERC annual report data to rank the Top 10 pipeline companies in three categories (miles operated, trunkline traffic, and operating income) for oil pipeline companies and three categories (miles operated, gas transported for others, and net income) for natural gas pipeline companies.

Positions in these rankings shift year to year, reflecting normal fluctuations in companies’ activities and fortunes. But also, because these companies comprise such a large portion of their respective groups, the listings provide snapshots of overall industry trends and events.

For instance, earnings for the Top 10 oil pipeline companies rose 12.75% compared with the 19% overall increase, suggesting that the upswing was both broad-based and led by smaller operators. The Top 10 companies’ share of the segment’s total earnings shrank accordingly, standing at 44% vs. the 46% share of earnings held in 2017.

Net income as a portion of natural gas pipeline operating revenues improved to 39% in 2018, the highest level in more than 11 years. Income as operating revenues for oil pipelines climbed to 57%, the highest ever.

Net income as a portion of gas-plant investment rose to 5.3%, continuing the growth to 3.7% that occurred in 2017. Net income as a portion of investment in oil pipeline carrier property reached 13.5%, eclipsing 2017’s recent high of 12.4%.

Major and nonmajor natural gas pipelines in 2018 reported total gas-plant investment of roughly $197 billion, the highest level ever, up from $171 billion in 2017, $158.5 billion in 2016, $158 billon in 2015, $152 billion in 2014, about $147 billion in 2013, more than $142 billion in 2012, $139 billion in 2011, $125 billion in 2010, and more than $121 billion in 2009.

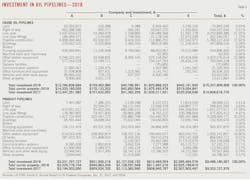

Investment in oil pipeline carrier property continued to surge in 2018, surpassing $122 billion, more than double the values seen just 6 years before. Carrier property in 2017 totaled $112 billion, up from 2016’s $99.5 billion, after reaching $93 billion in 2015, nearly $85 billion in 2014, $68 billion in 2013, topping $54 billion in 2012, hitting roughly $49 billion in 2011, more than $45 billion in 2010, and roughly $42 billion in 2009.

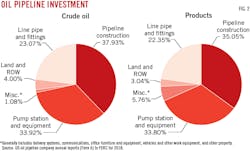

OGJ for many years has tracked carrier-property investment by five crude oil pipeline and five products pipeline companies chosen as representative in terms of physical systems and expenditures (Table 3).

The five crude oil pipeline companies in 2018 increased their overall investment in carrier property by more than $639 million (4.4%), bettering the gains seen the previous year but lagging the segment. All companies but one increased investment in carrier property, the outlier reducing its investment by roughly $600,000.

The five products pipeline companies, by contrast, saw their overall investment in carrier property slow in 2018, adding more than $162 million, or 1.7%.

Comparisons of data in Table 3 with previous years must be done with caution as mergers, acquisitions, and sales can make comparisons with previous years’ data difficult.

Fig. 2 illustrates how investments in the crude oil and products pipeline companies were divided.

Construction mixed

Applications to FERC by regulated interstate natural gas pipeline companies to modify certain systems must, except in certain instances, provide estimated costs of these modifications in varying degrees of details.

Tracking the mileage and compression horsepower applied for and the estimated costs can indicate levels of construction activity over 2-4 years. Tables 4 and 5 show companies’ estimates during the period July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2019, for what it will cost to construct a pipeline or install new or additional compression.

These tables cover a variety of locations, pipeline sizes, and compressor-horsepower ratings.

Not all projects proposed are approved. And not all projects approved are eventually built.

- Roughly 246 miles of pipeline were proposed for land construction, with no offshore work submitted. The land level was sharply lower than the roughly 545 miles proposed for land construction in 2017, the nearly 2,500 miles proposed for land construction in 2016 and the 2,192 miles proposed for land construction in 2015.

- New or additional compression proposed by the end of June 2019 measured nearly 292,000 hp, only slightly above the 287,000 hp proposed the year before, which was down sharply from the nearly 600,000 hp proposed in 2017 and the 2.2 million hp proposed in 2016.

Putting the reduced US gas pipeline construction in perspective, Table 4 lists 18 land-pipeline “spreads,” or mileage segments, and 0 marine project compared with:

- 11 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Oct. 1, 2018, p. 60).

- 27 land and 1 marine projects (OGJ, Oct. 2, 2017, p. 71).

- 33 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 5, 2016, p. 89).

- 46 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 7, 2015, p. 114).

- 31 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 1, 2014, p. 122).

- 26 land and 2 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 2, 2013, p. 117).

- 11 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 3, 2012, p. 118).

- 31 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 5, 2011, p. 97).

- 8 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Nov. 1, 2010, p. 108).

- 21 land and 0 marine projects (OGJ, Sept. 14, 2009, p. 66).

None of the spreads in 2019 measured 100 miles or more, the longest proposed project being 42 miles in Virginia. Two of the spreads in 2018 measured 100 miles or more, their combined mileage constituting the bulk of that year’s proposed work.

For the 12 months ending June 30, 2019, the 18 land projects filed would coast an estimated $1.1 billion, as compared with 11 land projects for $5.4 billion a year earlier.

These statistics cover only FERC-regulated pipelines. Many other pipeline construction projects were announced in the 12 months ending June 30, 2019, but lied outside FERC’s jurisdiction.

A report released June 2018 on behalf of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America concluded that the US and Canada will require annual average midstream natural gas, crude oil, and NGL infrastructure investment of roughly $44 billion/year, or $791 billion (in 2016 dollars) total, from 2018 to 2035, up sharply from the $546 billion projected in the 2016 edition of the report. Most of this expenditure (roughly 53%) will be dedicated to natural gas development, with crude oil getting roughly 41% and NGL-related assets the remaining 6%.

Included in the $44 billion/year are:

- $15 billion/year for new oil and gas lease equipment.

- $14.7 billion/year for oil, gas, and NGL pipeline development.

- $8.4 billion/year for gathering and processing investment.

- $5.8 billion/year to support refining, storage, and export activities.

The report also forecast the need for about 41,000 miles of pipeline and 7 million hp of compression and pumping to transport oil, gas, and NGLs from 2018 through 2035 and an additional 139,000 miles of gathering line and 10 million hp of compression and pumping to support gathering, processing, and storage.1

The report assumes US GDP growth of 2.1%/year, Henry Hub natural gas prices averaging $3.30/MMbtu through 2035, and West Texas Intermediate crude prices averaging $75/bbl by 2025.

Against this backdrop, estimated $/mile costs for new projects as filed by operators with FERC returned to historical norms from last year’s highs. For proposed onshore US gas pipeline projects in 2018-19 the average cost was $4.6 million/mile, down sharply from the $9.95 million/mile average estimates from 2017-18 and also lower than the 2016-17 average cost of $5.9 million/mile, the $7.65 million/mile 2015-16 average costs, and the 2014-15 average cost of $5.2 million/mile. In 2013-14 the average cost was $6.6 million/mile as compared with $4.1 million/mile in 2012-13, $3.1 million/mile in 2011-12; $4.4 million/mile in 2010-11; and $5.1 million/mile in 2009-10.

Cost components

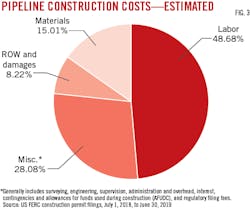

Variations over time in the four major categories of pipeline construction costs—material, labor, miscellaneous, and right-of-way (ROW)—can also suggest trends within each group.

Materials can include line pipe, pipe coating, and cathodic protection.

“Miscellaneous” costs generally cover surveying, engineering, supervision, contingencies, telecommunications equipment, freight, taxes, allowances for funds used during construction (AFUDC), administration and overheads, and regulatory filing fees.

ROW costs include obtaining rights-of-way and allowing for damages.

For the 18 spreads filed for in 2018-19, cost-per-mile projections fell in all categories except ROW. In 2011 miscellaneous charges passed material to become the second most expensive cost category and in 2017 they passed labor costs to become the most expensive category. This year, however, labor cost reclaimed its throne despite falling more than 44.5%:

- Material—$691,474/mile, down from $1,305,974/mile for 2017-18.

- Labor—$2,243,051/mile, off sharply from $4,042,625/mile for 2017-18.

- Miscellaneous—$1,294,388/mile, plunging lower from $4,238,543/mile for 2017-18.

- ROW and damages—$379,154/mile, relatively unchanged from $366,622/mile for 2017-18.

The reversal of labor and miscellaneous costs’ rankings was driven by continued high demand for labor at the same time proposed projects got smaller, limiting the amount needed for contingencies in operators’ estimates.

Table 4 lists proposed pipelines in order of increasing size (OD) and decreasing lengths within each size.

The average cost-per-mile for the projects rarely shows clear-cut trends related to either length or geographic area. In general, however, the cost-per-mile within a given diameter decreases as the number of miles rises. Lines built nearer populated areas also tend to have higher unit costs.

Additionally, road, highway, river, or channel crossings and marshy or rocky terrain each strongly affect pipeline construction costs.

Fig. 3, derived from Table 4, shows the cost-component splits for pipeline construction.

Labor is the most expensive category and the most volatile. Labor’s portion of estimated costs for land pipelines rose to a recent high of 48.7% in 2019 from 40.6% in 2018, 35.8% in 2017, 47% in 2016, 37.8% in 2015, 42.4% in 2014, 38.8% in 2013, 44.6% in 2012, 44.3% in 2011, and 44.5% in 2010. Material costs for land pipelines, meanwhile, rose to 15% of the total from 13.1% in 2018, 22.4% in 2017, 13% in 2016, 19.3% in 2015, 13.6% in 2014, 23.2% in 2013, 16% in 2012, and 14.5% in 2011.

Fig. 4 plots a 10-year comparison of land-construction unit costs for material and labor.

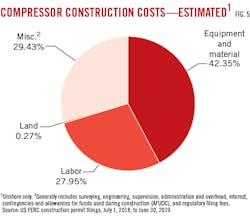

Fig. 5 shows the cost split for land compressor stations based on data in Table 5.

Table 6 lists 10 years of unit land-construction costs for natural gas pipeline with diameters ranging from 8 to 36 in. The table’s data consist of estimated costs filed under CP dockets with FERC, the same data shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 6 shows that the average cost per mile for any given diameter may fluctuate year-to-year as projects’ costs are affected by geographic location, terrain, population density, and other factors.

Completed projects’ costs

In most instances, a natural gas pipeline company must file with FERC what it ended up spending on an approved and built project. This filing must occur within 6 months after a pipeline’s successful hydrostatic testing or a compressor’s being put in service.

Fig. 6 shows 10 years of estimated vs. actual costs on cost-per-mile bases for project totals. The spike in both categories for 2014 and 2017 stemmed from a larger-than-usual proportion of mileage completed being in high-cost urban northeast US settings.

Tables 7 and 8 show actual costs for pipeline and compressor projects reported to FERC during the 12 months ending June 30, 2019. Fig. 7, for the same period, depicts how total actual costs ($/mile) for each category compare with estimated costs.

Actual costs for pipeline construction were almost $500,000/mile more than estimated costs for the same projects. The bulk of this difference came in labor costs, which were roughly $1.1 million/mile (50%) more than projected for the 12 months ending June 30, 2019. Both labor and right-of-way costs were greater than estimated.

Two pipeline projects completed in the 2018-19 window reported more than $1 billion in labor alone. Sabal Trail Transmission LLC—a joint venture of Spectra Energy Partners, NextEra Energy Inc., and Duke Energy—laid 509 miles of 24 and 36-in. OD pipe in Alabama and Florida at an overall cost of nearly $2.6 billion, including labor costs of almost $1.1 billion. Despite contractor costs, however, that ran $328 million over estimates, the project was completed for $85 million less than had been forecast.

The Central Penn Line South portion of Williams’ 1.7-bcfd Atlantic Sunrise project used 125.2 miles of 42-in. OD pipe. Labor costs of roughly $1 billion were more than double filed estimates and made up the bulk of the project’s total $1.6 billion price, $437 million more than had been estimated. FERC approved Atlantic Sunrise in February 2017. Construction was dogged by protests and legal challenges but the line entered service in October 2018.

Some projects listed in Table 7 (like Atlantic Sunrise) may have been proposed and even approved much earlier than the 1-year survey period. Others may have been filed for, approved, and built during the survey period.

If a project was reported in construction spreads in its initial filing, that’s how projects are broken out in Table 4. Completed projects’ cost data, however, are typically reported to FERC for an entire filing, usually but not always separating pipeline from compressor-station (or metering site) costs and lumping various diameters together.

The 12 months ending June 30, 2019, saw more than 680,000 hp completed, roughly 62% more than the year before. Actual compression costs of $3,352 were 2.5% higher than estimates, driven by labor costs nearly 50% above what initially had been filed (Table 8).

References

- ICF International, “North American Midstream Infrastructure Through 2035; Significant Development Continues,” June 18, 2018.

About the Author

Christopher E. Smith

Editor in Chief

Chris joined Oil & Gas Journal in 2005 as Pipeline Editor, having already worked for more than a decade in a variety of oil and gas industry analysis and reporting roles. He became editor-in-chief in 2019 and head of content in 2025.