Key Highlights

- PetCoke LWP, derived from petroleum coke, offers a lightweight, chemically stable proppant that enhances fracture reach and production uplift without requiring special pumping procedures.

- Field trials in Midland and Delaware basins show PetCoke LWP creates longer, more conductive fractures, resulting in increased oil recovery and improved fracture uniformity compared to traditional sand treatments.

- Ultralight ceramsite prevents premature bridging during horizontal gravel packing but may compromise long-term stability due to lower packing density, necessitating a balanced approach in material selection.

- Laboratory and simulation studies indicate that moderate reductions in gravel density improve dune migration and packing efficiency, while excessive lightness can lead to unstable gravel packs and reduced long-term performance.

New lightweight proppants (LWP) have been developed for fracturing and gravel packing service. ExxonMobil Corp. (XOM) developed a petroleum coke-derived product (PetCoke LWP) as an additive in propped fracture treatments for more effective packing of distal fracture extensions, and light weight ceramics have been used to more effectively pack horizontal wells.

Lab studies and field trials showed that Petcoke LWP enhanced fracture reach. It is chemically stable, operationally sound, and produces measurable production uplift. Operational trials confirmed that Petcoke LWP pumps like sand without special procedures.

A study of ultralight ceramic proppant (ceramsite) in horizontal-well service showed that it prevented premature bridging. At too light a density, however, it produced an unstable gravel pack which undermined long-term production stability. A medium-light ceramsite derivative struck a balance between effective dune migration and tight packing.

LWP for fracturing

Slickwater fracturing does not effectively prop the entire wetted fracture because slickwater poorly suspends proppant. Sand settles too quickly for deep horizontal and vertical transport into the fractures. This transport inefficiency restricts pathways through the fracture network. Unpropped fractures contain orders-of-magnitude less conductivity than propped fractures, and this low conductivity declines further with depletion. Inefficient proppant transport also limits the reach of effective fractures, resulting in non-ideal well spacing and smaller effective stimulated reservoir volume than the overall fracture network would suggest.

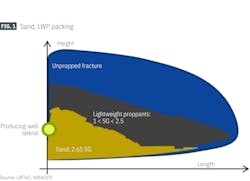

Conventional ceramic- or porous-media lightweight and ultralightweight proppants suffer from high cost, low compressive strength, or unsuitable particle size for fracture applications. Petcoke LWP meets fracturing requirements but is not proposed as an entire replacement for traditional sand or ceramic proppants. Petcoke LWP should be tailed into the fracture job as an additive to the overall proppant package. During the job, the traditional proppant will settle on the low and relatively near-wellbore area of the fracture network, while Petcoke LWP flows upward and outward into the fracture, extending the overall conductive area (Fig. 1).

Petcoke LWP properties

Petcoke LWP density measures 1.4-1.6 g/cc, almost half the average sand density of 2.65 g/cc. Petcoke LWP sieved for fracture service has a 0.155-mm mean particle diameter, which closely matches 100 mesh (0.149 mm), and its size distribution is tighter than typical Permian basin regional sand. API K-crush tests show that Petcoke LWP has a similar crush strength as regional Permian basin sands.

Although 100-mesh Petcoke LWP has lower conductivity than 100-mesh sand under API conductivity test conditions, the difference is less than an order of magnitude even at high closure stress. Petcoke LWP and sand mixtures performed similarly to sand alone, and fractures propped with either Petcoke LWP or Petcoke LWP-sand mixtures have conductivities several orders of magnitude higher than wetted but unpropped fractures.

Petcoke LWP’s lighter density exhibits 7-10 times less terminal settling velocity in Permian basin produced water than similarly sized sand. Flow tests through a slot-flow apparatus which simulates a 4-ft high x 8-ft long x ⅛-in. wide fracture confirmed that Petcoke LWP remains suspended and travels farther into fractures than sand under a range of injection rates.

Petcoke LWP is inert under normal fracturing and producing conditions. It contains long-chain hydrocarbons with nonorganic elements bound within the hydrocarbon chain, and potentially reactive functional groups cleave during the coking process.

Extended soak tests in water, acid, and base solutions representing typical chemicals in fracturing treatments showed minimal leeching or changes in chemical structure. Petcoke LWP also did not react with HCl, a common stimulation chemical.

Additional exposure tests to hydrocarbons typically encountered in producing wells evaluated material stability in producing environments. Samples of Petcoke LWP soaked in Permian basin produced oil for up to 8 weeks at elevated temperature and pressure (150° F. and 5,000 psi) showed no degradation, discoloration, or loss of strength. The material’s stress-strain profile matched that of a control sample.

Petcoke LWP operations

After qualifying the material for use, a logistics trial tested the feasibility of commercially sieving, transporting, storing, and pumping Petcoke LWP in a fracture stimulation. The initially produced product contains particles >1 mm in size and requires sieving to 100–mesh size. Additionally, fines must be removed to minimize dust during transport and interstitial plugging in the pack.

A pilot-scale sieving facility received raw Petcoke from a nearby ExxonMobil affiliate refinery in Canada. Conventional sand-sieving equipment sieved the material to 100 mesh. On-spec product was shipped via closed-top hopper railcars to the Permian basin where it was stored, metered, and blended at the wellsite using similar processes and equipment for sand.

Petcoke LWP required similar PPE and pumping procedures as sand, without special variances. Pumping trials confirmed that Petcoke LWP pumped like a typical sand slurry, requiring no special procedures. Treating pressures were slightly lower than expected, possibly due to improved material transport or reduced friction.

Midland basin field trail

Two field trials conducted in Midland basin evaluated fracture density, depletion, and production from treatments using mixtures of Petcoke LWP and sand.

The first trial compared alternating sand-only stages with Petcoke LWP-sand stages in a treatment well. All treatments used 100-mesh material in slickwater. The Petcoke LWP stages mixed the material with standard 100-mesh sand. A dedicated slant monitoring well, equipped with fiber optics and pressure gauges at the same landing depth as the treatment well, measured lengths of the created and conductive fractures. This trial could only measure fracture geometry in one dimension.

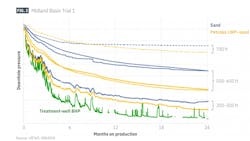

Both treatment designs exhibited similar fracture density near the wellbore, but the density dropped faster with distance for the sand-only completions. Petcoke LWP created longer conductive fractures which extended beyond 600 ft.

After 2 months of production, the Petcoke LWP design showed about 20% longer average conductive frac length than the sand-only design. Fig. 2 shows that depletion trends between the two designs consistently diverge from 500-650 ft, where the Petcoke LWP treatment depletes more rapidly. Beyond 700 ft, the sand-only completion did not exhibit a long-term pressure decline, indicating that the treatment did not produce effective fractures at this distance. The Petcoke LWP completion, however, showed depletion at this distance during a 2-year monitoring period.

The second trial compared one well treated with Petcoke LWP with two sand-only wells on either side. Total proppant and fluid volumes were equivalent in all three wells. The wells exhibited no interference and were considered independent.

After 1 year of production, the Petcoke LWP treated well exhibited a 10% uplift in cumulative oil compared with sand-only wells. Examination of flowback solids showed only trace Petcoke LWP at surface with less Petcoke LWP/sand volume fraction than originally pumped. These results indicated that the increased buoyancy of the Petcoke product did not result in flowback problems.

Delaware basin field trail

Three Delaware basin trials evaluated Petcoke completions with respect to fracture density, depletion, and production. In the first trial, two slant monitoring wells determined the length of in-bench fractures and extent of vertical fractures in a test well containing alternating sand-only and mixed Petcoke LWP-sand stages. The mixed stages varied in ratios of sand and Petcoke LWP, but each stage contained the same total proppant and fluid loading.

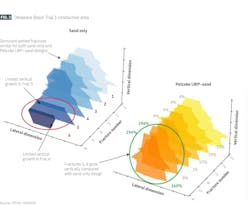

Addition of Petcoke LWP to the stages improved fracture uniformity and increased conductive area by 40% (Fig. 3). Conductive Petcoke LWP-containing fractures extended 100-200 ft further away than the volume equivalent sand-only stages. Fiber optics observed greater fracture uniformity during stimulation with Petcoke LWP-sand stages than for sand-only completions.

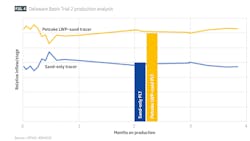

A second Delaware basin trial stimulated a well with alternating sand-only and Petcoke LWP-sand stages but with stage-level variations in the Petcoke-sand ratio. Total proppant and fluid loading remained constant per stage.

Oil soluble tracer added in each stage and a production logging tool (PLT) run provided production profile analysis. The PLT provided quantitative assessment of relative inflow performance for a single point in time, while tracers monitored long-term trends before and after running the PLT.

Tracers and PLT analyses showed that the average per-stage production contribution from the Petcoke LWP-sand stages outperformed sand-only stages by at least 20% (Fig. 4). This behavior did not change during the first several months of production.

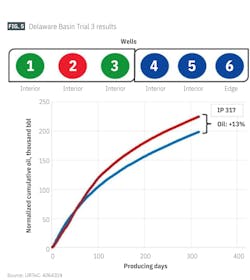

A third Delaware basin trial, conducted in the deepest developed bench in the region, included six wells: five interior and 1 edge. Well 2 on the interior contained a Petcoke LWP-sand mixture, while the other wells contained only sand. The total volume of proppant was constant in all six wells.

The wells were in an isolated bench with limited interbench pressure communication but moderate intrabench pressure communication. Because Petcoke LWP probably created an enhanced fracture network affecting adjacent control wells, a more complicated analysis was required than the Midland multi-well with isolated wells. As indicated in Fig. 5, Wells 1, 2, and 3 were grouped together (green and red) as Petcoke LWP-influenced wells. Their average production during 317 producing days was compared with sand-only Wells 4, 5, and 6 (blue).

The three Petcoke LWP-influenced wells outperformed the control wells by 13%. The higher uplift numbers seen with this methodology was likely due to a larger effective fracture network created around the Petcoke LWP well, impacting the surrounding wells.

Production analysis of wells in true isolation analysis compared cumulative oil from Well 2 with Well 6 at the edge. Typically, edge wells outperform interior wells. In this case, however, the interior Petcoke LWP well outperformed Well 6 by 18%.

ExxonMobil estimates that it used Petcoke LWP in about a quarter of its wells in Permian basin in 2025 and will use it for about half of new wells in 2026. At peak usage, the company expects to pump about 2 million tons/year of LWP in the Permian basin.

LWP for horizontal gravel packing

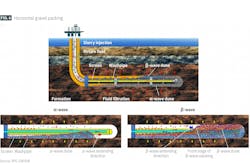

Gravel packing is a widely adopted technique in oilfield operations to prevent sand production. Horizontal gravel packing is a specialized completion scheme which requires pumping gravel laterally to achieve full screen coverage in the well. The first phase of the process deposits a gravel bed on the bottom of the well through sand-dune migration in an initial wave (α-wave, Fig. 6). The dunes are ideally no higher than 2/3 of the wellbore to provide space for gravel to flow across the top to continually deposit as a wave to the end of the well.

Once the a-wave reaches the end of the well, a secondary β-wave backfills the space above the bed, starting from the end of the well and completing at the heel. A premature screenout occurs if the α-wave hits the top of the wellbore before it reaches the end of the well. The β-wave immediately packs the well before the bridge to the toe, but the pack remains incomplete beyond the bridge.

Effective horizontal gravel packing requires balancing fluid rate, gravel-fluid density ratios, fluid viscosity, gravel concentration, and pumping pressures in real time. Lightweight proppants have been used in this application, to varying degrees of success.

A recent technical study evaluated how density differences between the sand-carrying fluid and the gravel affect horizontal packing. The studies focused on dune migration patterns, packing efficiency, and long-term pack stability using large-scale simulation experiments with water as the sand-carrying fluid and conventional, light, and ultralight densities of ceramic gravel.

The experimental system was designed to replicate real-world conditions and included a well simulation unit, reservoir simulation unit, pumps, tanks, mixers, sensors, and flowmeters. Real-time monitoring of pressure, flow rate, filtration loss, and other parameters analyzed the packing process.

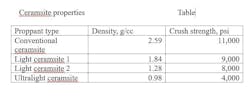

The experiments used 16-30 mesh gravel and prepared slurries with varying viscosities of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide. In keeping with ISO 13503-2 standards, compressive strength tests were performed on different ceramsite (a ceramic proppant material) densities. Ultralight ceramsite, with a density of 0.98 g/cc, exhibited the lowest compressive strength at 4,000 psi, while conventional ceramsite, with a density of 2.58 g/cc, had a compressive strength of 11,000 psi (Table).

The study compared the packing effects of these materials and revealed distinct differences in dune formation and migration patterns. With conventional ceramsite, the high gravitational force and lower buoyance between particle and fluid resulted in downward-deposited dunes during the α-wave packing process. These dunes rose quickly, forming premature bridges that blocked slurry migration toward the toe of the wellbore, leaving sections unpacked.

Light ceramsite, with a density of 1.28 g/cc, experienced higher buoyancy and lower gravitational force in the well. The material prevented premature bridge formation and allowed dunes to migrate further, extending the sandbed length and enabling normal β-wave reverse packing.

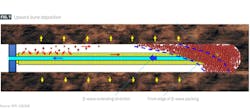

Ultralight ceramsite behaved differently. With a density lower than the fluid, it remained suspended and formed upward-deposited dunes (Fig. 7). These dunes migrated rapidly to the toe of the wellbore and then slowly reversed toward the heel, redistributing the pack unevenly. While it prevented premature bridging, it compromised packing density and reduced long-term stability. This finding highlighted the trade-off between preventing premature bridging and achieving adequate compaction.

Pump-pressure data confirmed these observations. With ultralight ceramsite, pressure remained stable until the suspended bed reached the toe, after which resistance increased and pressure rose gradually. By contrast, higher density ceramsite increased slurry resistance and pump pressure more quickly, with premature bridging occurring at distances from the heel at which the fluid velocity could no longer effectively carry the particles forward.

The study concluded that moderate reduction in gravel density broadens the operational window and improves packing, but excessive reduction has negative consequences. Quantitative analysis showed that increasing ceramsite density to 2.59 g/cc from 0.98 g/cc decreased packing ratio (ratio of actual packed gravel volume to wellbore annulus volume) by 39% and safety index (measure of likelihood of premature screenout) by 21%. The heavier gravel, however, improved packing density (ratio of packed density to individual gravel particle density) by 100%.

Fig. 8 shows how low packing density can lead to areas with exposed holes in the pack. These areas expose the screen, and subsequent sand production either erodes the screen or fills the hole in the gravel pack with low-permeability material, altering efficient drainage and drawdown patterns.

Although higher packing density enhances deposition and compaction, depositing this sort of pack narrows the safe operating window due to increased resistance and bridging risk. Ultralight ceramsite may prevent premature bridging, but its reduced packing density risks long-term stability. The optimal density range was identified as 1.28-1.78 g/cc (Fig. 9).

The report also examined the interaction of gravel density with other parameters such as fluid viscosity, pump rate, and gravel concentration. High-density gravel improved packing density significantly but reduced packing ratio and safety. When combined with high viscosity, packing density increased further, but safety declined sharply, underscoring the need for balanced operating conditions.

These results suggest that while certain combinations may enhance long-term stability, they require robust wellbore pressure containment to be viable. The study emphasized that enhancing one performance aspect often leads to trade-offs in others. For example, increasing viscosity and pump rate improved packing ratio but reduced safety substantially, highlighting the importance of achieving holistic optimization rather than focusing on individual parameters.

Bibliography

ExxonMobil third-quarter 2025 earnings call, Oct. 31, 2025.

Grubac, G., Gullickson, G., Bonneville, A., Brand, P, Goloshchapova, D., Dunham, E.M., Khan, M., Cuthill, D., Shokanov, T.A., Gibson, C., Palisch, T., Hopp, C., and Nakata, N., “Enhanced Geothermal System Propped Stimulation >300°C: From Design to Implementation Phase I,” SPE–228078–MS, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, Tex., Oct. 20–22, 2025.

Jacobs, T., “Is ExxonMobil’s Proprietary Proppant a One-Off Advantage, or Can the Rest of the Unconventional Sector Follow?,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, Dec. 1, 2025.

Liu, C., Dong, C., Zhang, Y., Zhan, X., Yuan, Z., and Li, S., “Gravel Packing in Long Horizontal Well: New Insights into Dune Migration Patterns and Packing Parameter Optimization,” SPE–230318–PA, SPE Journal, Oct. 17, 2025, pp. 1–20.

Raz Haydar, R. and Fakher, S., “Developing Fly Ash Based Proppants and Evaluating Their Load Bearing Capacity for Hydraulic Fracturing,” SPE–225632–MS, SPE Europe Energy Conference and Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, June 10–12, 2025.

Shirley, R., Spiecker, P.M., Brown, J.S., Benish, T., Jin, X., Kulkarni, M.G., Kao C-S., Gordon, P.A., Moffett, T.J., Kumar, S., and Staus, G., “Development of a Novel, Patented Fracturing Technology Based on Low-Cost Petroleum Coke Light Weight Proppant from Lab-Scale Evaluation to Field-Scale Pilots: Case Studies in the Midland and Delaware Basins,” URTeC: 4264319, Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Houston, Tex., June 9–11, 2025.

About the Author

Alex Procyk

Upstream Editor

Alex Procyk is Upstream Editor at Oil & Gas Journal. He has also served as a principal technical professional at Halliburton and as a completion engineer at ConocoPhillips. He holds a BS in chemistry (1987) from Kent State University and a PhD in chemistry (1992) from Carnegie Mellon University. He is a member of the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE).