Managing risk in offshore rig construction: An equipment supplier’s perspective

Harold Conway & Edward E. Will, Cameron - Houston

We have witnessed a dramatic shift in the offshore drilling construction and equipment sector in the last 12 to 15 months. As recently as the spring of 2005, the major players in the sector, including several of the largest offshore drillers, still publicly doubted that rig construction economics had reached the turning point needed to stimulate a robust cycle of rig building akin to the 1980s.

To be fair, nothing will probably ever compare to the heyday of rig construction and offshore rig fleet growth seen in the early 1980s, but the current market is certainly a strong runner up. Both rig builders and critical component suppliers are now almost universally near or at capacity, pushing lead times for floaters into the 2008 to 2010 timeframe.

The appearance of a number of new entrants into the offshore rig owner ranks has accelerated the consumption of global capacity in 2005 and 2006, and promises to continue to do so.

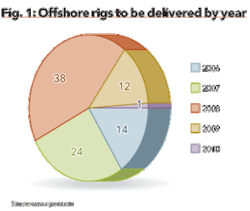

Figure 1 reveals that from 2007 to 2009, a total of 70 new offshore drilling rigs are scheduled for delivery. Figure 2 illustrates the historical delivery volume of new offshore drilling rigs over the last 10 years along with their cost.

Cameron’s Drilling Systems business supplies much of the key equipment for these rigs, including subsea blowout preventers and control systems, choke and kill manifold systems, and deepwater drilling riser and tensioner systems. These components perform critical pressure control functions and form the backbone of safe rig operations.

As such, many are engineered to specifically meet the design capabilities of the drilling unit. Because of their size, weight, and complexity, these systems require unique competencies to manufacture, deliver, and install and may involve 2 or 3 years to complete.

As drilling contractors add drilling rig capacity by building new rigs and refitting existing rigs with new technology to extend their use in deeper waters (or higher pressures and temperatures), the demand for sophisticated drilling systems has increased significantly. With delivery lead times growing, rig owners are looking for greater assurance that their equipment needs will be met. Most require long-term agreements with component suppliers prior to committing to the large investment in new offshore rigs.

The challenge for equipment suppliers is directly related to that of rig builders and rig owners - bridging the gap between the current environment and the likely rig delivery date three or four years hence. In essence, there is a certain level of inherent risk and uncertainty in executing a contract today that extends through the next year or two. That risk and uncertainty is greatly magnified when the critical event - rig construction and delivery - is not accomplished for 3 or 4 years.

Long Term Agreements (LTAs) are not new in the drilling equipment and services market. The cyclical nature of the E&P sector has taught us that these agreements can smooth the bumps in the road when events take an unexpected turn.

Unfortunately, most drillers have lived through several cycles in which some customer commitments wound up as empty promises. Traditionally, equipment suppliers have relied on LTAs to help negotiate with vendors for the purchase of items such as raw materials.

In today’s environment, contracting for the supply of equipment is much more complicated and, we believe, much riskier. Not only are traditional factors such as inflation, currency rates, and liability exposure present, but so too are new market challenges such as the rising cost of raw materials, energy, and changing regulatory requirements. All must be addressed to develop viable agreements for rig construction and delivery.

Execution risks

Agreements to supply equipment to offshore drilling rigs routinely involve multiple milestones for various component packages. These are generally procurement, buyer approval, build, delivery, final approval, and acceptance. These packages also typically require significant engineering and project management work by the supplier.

Both buyers and sellers need to identify the risks that may arise during project execution and after commissioning. These risks have a financial impact that can make the difference between delivering a project on time and profitably, versus late and at a huge loss.

Risks need to be handled up front during contract negotiations and the terms agreed to between the parties. The issues generally can be categorized into three groups - profitability, cash, and liabilities. These issues require buyers and sellers to answer a variety of questions that may arise during the execution phase or after commissioning.

The following examples are not exhaustive, but typical of the issues that, from a supplier’s perspective, may arise in connection with component purchases for offshore rig construction projects. Most of the supplier issues have important implications for buyers and end users as well.

Profitability

•Since these contracts have deliveries over a longer period, how do I protect myself from increases in prices from my vendors and from increasing labor costs?

•Similar to the above, how do I price for options (i.e. possible additional purchases) in the contract?

•What will happen if the customer (end user) cancels the drilling contract? Given that a number of rigs are currently being built on speculation, this has the potential to be a key problem for buyers.

•What if I am late on delivery on one of the packages?

•How should I manage scope creep or change during the execution phase?

•How do I manage the impact of currency fluctuations on profitability?

Cash

• Since many investors are financing rig building, how do I protect myself for the credit worthiness of the contracting party?

• Because these projects require significant investment of cash for purchasing inventory, how do I keep myself cash neutral during the project execution phase?

Liabilities

• How much exposure should my company have to consequential damages?

• How should I protect myself from pollution/reservoir damages?

• How much should I be held liable for non-performance for circumstances beyond my company¿s control?

• How should I manage exposure to injury or damage?

• What should my warranty terms be?

Using contracts to manage the risks

Managing risks contractually usually requires a joint effort by buyers and sellers to get similar terms with end-use customers (i.e., operators) - alignment of risk and responsibility is key.

For example, with long-duration deliveries, it is difficult to get firm prices from critical vendors in time to pass on a firm quote to the buyer. Additionally, there is frequently a time lag during negotiation of the contract to define technical specifications before placement of the purchase orders for long lead time materials on the vendors or subcontractors.

The result: Buyers need to build in expected inflation in material and labor in the price being submitted to the end-use customers for long duration deliveries. This has always happened to some degree. It needs to be rigorously pursued today.

Having a material escalation clause in the contract solves the problem. Such a clause protects against increases in price from vendors from time of quotation to time when the purchase order is launched on the vendor. Unless the buyer has a similar clause with the end-user/operator, it is difficult for buyers to agree to such terms with equipment suppliers.

Escalating rig rental rates must take account of this eventually. In a tight capacity market, it is nearly impossible to guarantee prices on equipment deliveries more than one year out. The only way to give a “firm” price is to subject it to such a clause.

Next, buyers and sellers need to identify the basis for the material escalation clause. It is not easy to find a public index that can be used as a proxy for material prices, unlike labor costs that can be tied to government labor indices.

For instance, over the years, Cameron has bought numerous steel forgings and has seen prices increase dramatically. The drivers behind those increases are both worldwide steel prices and the basic economics of supply and demand in a tight forgings market. In this instance, one solution is to identify a “basket of materials” in the contract along with their contractual price.

Similarly, one can price for options to purchase additional items using today’s market prices plus an inflationary factor for labor and material. These options should also be subjected to the same material escalation clause to be realistic.

Another unpleasant, but necessary, issue to address is termination, something that the drilling industry is all too familiar with due to cyclical downturns. When a customer terminates for convenience, the contract should provide for compensation for work performed to date and for reasonable costs incurred due to early termination.

Again, the pass thru to the end user is critical. Repetition of the unfortunate events of the late 1990s involving cancellation of rig contracts is not acceptable today.

A related issue involves liquidated damages (LDs) as the sole provision for damages due to delay. Since delay of key equipment can hold up a rig delivery, negotiating the amount of LDs upfront is significant.

On the same note, however, there should be a “no harm/no foul” clause if the lateness does not cause the buyer to incur any penalties. Needless punitive provisions add risk and uncertainty to a process that already has enough unavoidable uncertainty and cost built into it.

The inherent nature of offshore projects often results in scope changes during execution. The problem is usually solved by having mutually agreed-upon “design freeze” dates in the contract, along with a checklist of other information that requires mutual agreement along with due dates for those specific items. Changes outside the scope or after the design freeze should be subject to variation orders.

Other key contractual risk factors involve the currency market and the collection of cash. Hedging of currency of receipt to match with the currency in which costs are incurred is another key financial risk issue negotiated by buyer and seller.

Collection risks are accentuated because the current market has attracted several relatively new players and large value contracts expose the value chain to significant collection risks especially if there are sudden downturns. The use of parent company guarantees or bank guarantees minimizes these risks and potential surprises. In addition, collection of progress milestone payments helps minimize the risk of credit failure to suppliers.

Finally, liabilities need to be allocated between parties fairly and reasonably. The basic theme is that these liabilities must be capped. There is too much at stake for a company not to limit these costs. Events such as loss of production, loss of profit, and reservoir damage can alter the economics of the entire drilling program.

Similarly, unanticipated force majeure events such as hurricanes, war, terrorism, etc. need to be recognized in the context of contractual relief for non-performance. “Knock-for-knock” indemnity provisions for injury or property damages represent another discussion item between buyers and sellers. Where appropriate, warranty should cover only the repair or replacement of the defective equipment supplied and not ancillary costs.

Summary

Dealing with the above risks as early as possible during the contract negotiation phase is time consuming and difficult for both parties. Successful treatment of these risks can save a lot of trouble down the road during project execution if both parties have agreed upon risk allocation.

Operators and drilling contractors need to be flexible during contract negotiations to identify and allocate risks appropriately. Since they sit at the top of the value chain, flexibility on their part on contract terms ripples down the chain ensuring stability among equipment suppliers. The industry is much more interdependent now than at any time in its history and sound financial principles need to guide commitments and responsibilities between buyers, sellers, and end-users of critical drilling assets.

The authors

Harold Conway has served as president, drilling systems for the Cameron division of Cooper Cameron Corp. in Houston since October 2005. Previously, he was vice president and general manager, eastern hemisphere, based in London. Conway has been with Cooper Cameron companies since 1974 and has held various management positions with Cooper Industries, Joy Manufacturing, and ACF Industries. He holds a BBA degree from the University of Notre Dame.

Edward E. Will has been vice president, marketing for Cameron since April 2001. He was previously vice president, surface and subsea business and also served as vice president, business development. Will came to Cameron from Weatherford. Prior to that he served as president of the international division of the Western Company of North America and as vice president for several divisions of NL Industries/Baroid Corp. Will has an MBA from The Harvard Business School.