Accelerating revenue and margin growth

Pradeep Anand, Seeta Resources,Houston

There are only four factors that contribute to growth in top-line revenue:

1) Market Drivers - factors that drive market demand for your and your competitors’ products and services. 2) Market Share - your share or slice of the pie. 3) Pricing - your ability to capture a share of the value that you deliver to your customers. 4) Product/Service Portfolio - the sum of the revenues contributed by the addition of new products and dropping old products from your portfolio.

These are the only four factors to consider when you want to accelerate year-to-year top line revenue growth. Doing nothing different, and going with the flow is the easiest to execute, since the current rising tide (of oil prices) will raise most boats. Alternatively, firms can take advantage of industry market drivers, expend effort in increasing market share, rationalize their product portfolio to refocus their organizational resources, and develop effective, real-time pricing strategies and tactics to accelerate growth.

In the near term, the avenues for growing revenues and margins are:

1) taking advantage of positive trends in market drivers;

2) rationalizing the product/service portfolio;

3) improving pricing tactics; and

4) increasing market share.

Experience has shown that these factors are not independent of each other but, in fact, when executed in a holistic manner, they have multiplicative effects, yielding surprisingly explosive results.

Take advantage of market drivers

Technological, political, environmental, regulatory, cultural, demographic, economic, and other factors have far-reaching consequences on the marketplace. Detecting, monitoring, and analyzing these reveal nuggets of trends and discontinuities that, in turn, create opportunities or threats to a firm. Early detection of trends and discontinuities create dramatic competitive advantages.

For example, in the upstream business, the trend in the price of oil is one of the important drivers to consider. When prices have an upward trend, the market is driven by greed, and oilfield service (OFS) companies show growth because of oil companies’ need and demand for greater capacity.

When prices have a downward trend, fear sets in, and oil companies are driven by the need to change business models and designs that assure profitability in declining environments. OFS companies that grow in this environment are those that contribute value through new “faster, better, cheaper” models of exploring and producing oil and gas. Experience has shown us that the current upward trend is a double-edged sword.

One edge of this sword is the higher oil price-driven spike in E&P activity - with the price hovering well in excess of $40/bbl and expectations of staying in $20 to $30 range in the planning horizons at oil companies, many projects that were considered marginal a few years ago have crept up into the zone of positive and acceptable return on investment.

The overall economics of the industry are positive, but some areas are more positive than others. For example, a recent study by Douglas-Westwood forecasts that over the next five years, nearly 4,500 exploratory wells will be drilled offshore, costing $75 billion, and 10,500 development wells costing $114 billion. Drilling and completion expenditure for deepwater offshore wells is expected to increase to $56 billion in 2008 from the current $36 billion, and this creates revenue momentum for a few firms.

While these economic drivers will create much-needed wind in the sails, increasing utilization in segments of the offshore rig industry and other traditional segments, they will also catalyze and accelerate the growth of those specialty technologies that have had a long history of successes, and fit into oil companies’ E&P processes.

For example, every exploration decision is gigantic in magnitude and fraught with uncertainties, thereby increasing the value at risk. Consequently, specialty technology firms and people in “exploration modeling” or “petroleum systems modeling” - those who have the ability to reduce the value at risk by integrating information from multiple disciplines and methodically estimating charge, trap, and reservoir risks - are reaching the tipping point, where demand for services will far exceed supply.

Their presence is not yet a panacea in the industry but thanks to the growing exploration risk in the industry, 3D exploration modeling and petroleum systems modeling are today where 3D seismic interpretation was in the late 1980s. Firms such as Integrated Exploration Systems (www.ies.de) and basin modeling professionals, who have been operating in the core of E&P processes at leading-edge oil companies, are well positioned for the future.

The other edge of this sword is that accompanying these high prices there is increased reluctance to try new products and services. Financial results are assured with the current economic environment and the risk of trying something new far outweighs the returns.

Recent history shows us that the greatest shift in new technology acceptance in the industry came after 1986 when oil prices were severely depressed. The then-current business and operating models at oil companies and service companies were grossly inadequate and had to be changed. The industry’s mantra of technology being the vehicle for change was actually turned into action, and the then-nascent 3D seismic, LWD/MWD, horizontal drilling, and other technologies found rapid acceptance. The rotten economic environment was the perfect crucible for innovations to permeate through the industry.

Besides the economic conditions, demographics played a critical role in improving industry economics. 1986 also initiated a changing of the guard, with the torch being handed over to the new generation in the industry. This greatly helped new technology penetration. This generation did not carry with it the baggage of the earlier one of “this is how we do things” and charted new paths, with great results. However, today this generation has become the risk-averse old guard that inhibits and hinders penetration of new technologies.

It is counter-intuitive but when the good times roll, the beneficiaries are proven technologies - even nascent ones - and not new, untested ones, at least not in the E&P industry. This has significant implications at oil companies and, more so, at OFS firms, especially in the commercialization of new technologies.

Rationalize the product/service portfolio

Firms in mature industries, including the E&P industry, are like pack-rats, storing away immensely unprofitable products, drawing away resources from potentially higher-value products that could sharpen the firm’s competitive edge, and accelerate revenue and profit streams. It is amazing how often Pareto’s Law (the Eighty-Twenty rule) reveals itself, especially at firms with long histories.

Smart firms monitor the financial underpinnings of every product family on an ongoing basis, so that limited resources can be appropriately directed, in a timely fashion, to the ones that have the highest net present value (NPV). It is a purely financial exercise where internal resources - marketing, product development, R&D, manufacturing, operations, and financial people - work dispassionately in determining the NPV of various products and services at the firm, deriving probabilities-based expected value of every product line - dropping old ones and adding new ones.

Firms have hidden assets that are valuable to customers and these have a tendency to emerge during this process. If executed poorly, the product portfolio exercise can be a painful process that bruises egos and enrages turf battles. This can be avoided if the product portfolio team collaborates at the outset and has a consensus on rules of engagement and decision criteria.

Because of this rationalization process, the force of the entire organization - its value chain - is now focused on the selected few rather than being spread thin across many. This has significant implications on short-term and long-term results. Of the four thrusts, rationalizing the product/service portfolio is the most controllable, and has the highest ratio of impact on revenues and profits to resources needed.

Improve price effectiveness

First, a definition: what is pricing? Pricing is your firm’s ability to create profits by capturing and extracting some (or all) the value that your firm delivers to its customers.

The profitability of your firm can be substantially increased with a disciplined approach of breaking down pricing processes into manageable components, and tying then all together with the right people working on the right details at the right time. The methodology is focused on creating profits, driven by extracting the value that your firm delivers to its customers.

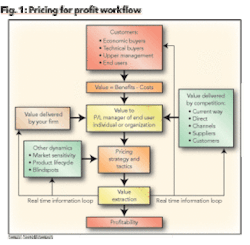

Fig. 1 shows a workflow for improving your firm’s profitability through pricing. However, this workflow to improve pricing effectiveness takes time and discipline to execute.

At a minimum, during the next fiscal year, your firm should be focused on value extraction and execution with the right people focusing on the right details at the right time.

Right People: The pricing organization cuts across traditional structures, going across all departments that touch the economic value delivered by your firm. However, the key people in the pricing decision process have two significant skills:

1) the ability to gather, process and synthesize diverse information in a dynamic environment, for decisions and actions; and

2) the ability to negotiate, to obtain what your firm is entitled to, in a fair and principled manner.

Pricing is everybody’s business. Every individual or group in an enterprise is a reservoir of internal and external information, relevant to pricing decisions. Harnessing these untapped reservoirs create further opportunities to increase your firm’s profitability.

Right Time: Pricing is a real-rime activity. Forget about price lists that are valid for specified periods. These are valid only if you are the sole player in the market, which for the majority is unlikely.

While the benefits delivered can stay static over time, a customer’s alternatives - your competition - will be active, making this a dynamic, real-time situation requiring real-time responses. Timely and accurate pricing decisions can only be accomplished when decision-makers have access to real-time information, from all domains - customers, markets, competition, value, your firm, and your business goals.

The greater the span and distribution of your firm’s resources, the greater is the challenge in synthesizing relevant information in relevant time.

Right Details: To spotlight the right details, factors that are internal and external to your firm come into play. Internal clarity in business goals combined with clarity in external forces expose the high priority details that need to be worked on. A simple rule of thumb: start on the outside and then turn inwards.

To improve the effectiveness of your firm’s pricing process is to change your firm’s pricing perspective - from being vendor-driven to being customer-driven. A vendor-driven pricing mentality creates some major blind spots. The most important and devastating of these is that your firm will fall into the trap of cost-based pricing, which will limit your firm’s profitability. Repeatedly, customer value-driven pricing has delivered more profitability.

Example: A firm is in the business of supplying “commodity” metal alloys for the mining industry. These alloys are abrasion resistant and are used to line earth moving and transportation equipment.

Customers’ purchasing agents and the firm had fallen into the groove of pricing on a unit weight basis, irrespective of performance of the alloys. The firm discovered that changing the perspective from “what the purchasing manager buys” to “what the CEO buys” gave insights for pricing a superior product.

The CEO of the firm was interested in production at the lowest cost with minimum down time. The hypothetical CEO’s expectations were in the length of time that the alloy performed and its cost, not in its weight.

In some instances, where data was available about the “expected value” of a commonly purchased benchmark, pricing was changed from a “per pound basis” to a “per day” basis, with the assurance that the client’s product would surpass the benchmark. This methodology changed the rules of the game in the industry and dramatically increased revenues of this superior product company.

Increase market share

To increase market share firms have to play from positions of strength, choose the right customer arenas, and competitors to confront. Since your firm has limited resources, it is appropriate to focus these on those strength-customer-competition combinations that yield maximum results, at the lowest risk.

To determine the optimum strength-customer-competition combinations revisit the following propositions:

Know Thy Customers: Central to a customer-driven strategy is the question: Who is the customer? Whether it is business-to-business environment (or a consumer), the customer has four dimensions: end user, technical buyer, economic buyer, and upper management, among many others. Errors in judgment in clearly defining your customer will lead to erroneous pricing, and, more important, leaving money on the table.

For all practical purposes, in a business-to-business situation, your customer is the P/L manager of the end-user organization. The rest of the players are influencers, filters, facilitators, and perhaps, resistors. The rubber meets the road and value meets costs in the end-user organization, or individual. Take your sights off this person or group, and you will quickly slip and slide down the slippery surface of declining share and pricing.

Revisit your underlying assumptions about customers. Ask seemingly generic questions to gain insights about the current nature of your customers. Who are your customers, both existing customers and prospects, in served markets and potential markets? Where are your customers? What do they buy from your competition? How do they buy? Why do they buy from you and your competition?

Answers to each question typically reveal a first level of understanding of the current nature of customers, especially about where revenues and margins are and whether they are migrating. However, delving deeper into the responses usually reveals nuggets that are critical for sales success.

Forget market segments - the devil is in the details and the E&P industry is small enough to list every customer, with business potential, and critical elements of the sales cycle, including decision makers, who can help strengthen your position or topple your competition, in your favor.

Know Thyself: Try to understand the secrets behind your successes in an objective manner. This is difficult but not impossible, if seen through customer lenses. Focus on: What do you sell to your customers? What do they buy from you? How do they buy? How do you deliver? Why do they buy from you and your competition? Where do they buy? When do they buy? What are the barriers to entry - for you and the competition?

The customer-lens driven “who, what, how, why, where, and when” of your sales, revenues, margins, and growth rates reveal many unseen, hidden aspects of your strategies. However, that is not enough. Your organization, customer intimacy, culture, assets, and skills in innovation, manufacturing, technology, finance (access to capital), information technology, management, marketing, and customer base (to name a few) are also important to understand your strengths.

While competitive analysis is somewhat objective, done from a distance, with limited information, self-analysis of your firm will be subjective. You will tend to be ultra-critical of your own firm. The challenge is to create an objective framework for self-evaluation. Typically, the criteria developed to critically dissect the competition easily transfers to objective self-analysis.

Know Thy Competition: The first issue is defining competitors in the market space. Your radar screen should be large enough to encompass direct and indirect customers. For example, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, very few firms in the E&P business saw 3D seismic interpretation’s ability to increase success rates and eliminate waste, as a threat to drilling budgets, and hence drilling activity.

There are at least four sources of competition:

1. Your Customer: The current way of doing business - “doing nothing” - is always an alternative to your customer. Moreover, it is not uncommon for customers to integrate backward and eliminate their suppliers. In these cases, a customer believes that there is greater value-add by embarking on producing the solution, under its control. Sometimes, “Not Invented Here!” or NIH raises its ugly head and prevents value recognition, but usually good sense eventually prevails.

2. Direct Competition with similar offerings: This is the most commonly accepted definition of competition. Of course, your solution must be differentiated- perceived by the customer as being different in important ways.

3. Your Channels or Intermediaries: There is only so much available margin in the market, and your distribution channels redirect some of that margin, to their coffers. While from a revenue perspective, a firm can be deluded into thinking that an intermediary is a channel partner. In reality, any entity between you and the end-user is a potential absorber of margin, with potential to increase its advantage with the end-user.

4. Your Supplier: This firm views your firm in the same light as you would your distributor, and could absorb your role. What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, and your supplier with the right leverage, can turn into a competitor.

Try to comprehend the strategic intents behind every one of your competitors and understand the secrets behind their successes, as seen through customer lenses. Like self-analysis focus on: What does each sell to your customers? What do they buy from them? How do they buy? How do they deliver? Why do they buy from your competition? Where do they buy from your competition? When do they buy from your competition?

The customer-lens driven “who, what, how, why, where, and when” of your sales, revenues, margins, and growth rates reveal many unseen, hidden aspects of competitive strategies. However, that again is not enough. Your competition’s organization, customer intimacy, culture, assets, and skills in innovation, manufacturing, technology, finance (access to capital), information technology, management, marketing, and customer base (to name a few) are also important to understand their strengths.

Insightful Synthesis: You cannot be everything to everyone, and the synthesis phase creates that optimum combination of customer-perceived strengths focused on specific customer arenas, with specific competitors - for maximum revenues and margins.

Execution and Implementation: The most challenging phase for an organization is the implementation phase. The process now becomes internally focused, controlled by your organization. The inertia of previous strategic and tactical directions and practices is significant - the more significant the departure from the existing path, the greater the power of resistance of “Not Invented Here” and “This is not the way we do things around here” syndromes.

Your firm’s leadership’s participation and blessing of the process and the results is the biggest catalyst to accelerated growth. It accelerates the ability of organizations to quickly drop old habits and assume new ones.

Example: A 50-year old equipment manufacturer (a client) considered itself to be a small player in a “mature” market. Growth was dependent on the rising tide of market activity. The firm believed that next growth area would be an international market where a significant number of new activities were being planned.

• An investigation of the customer behavior provided many insights:

• A majority of the available “margin” in the market was within the United States

• OEMs controlled this available margin, in the replacement market.

• Further investigation revealed that the incumbents took the replacement business for granted and would not compromise their entire installed base with a price war with a smaller player

• Customers were willing to consider timely alternatives to OEMs.

This firm developed a new initiative on the “replacement” business, developing information technology processes to assure timely delivery. The market demand program was focused on ongoing operations in the United States, with a guarantee - on time or it’s free. With this and several other programs, the firm’s revenues grew over 250% in about two years and margins about 400% during the same period.

Another Example: A firm manufactured process equipment, with applications that spanned several industries. During the investigative phase to determine segments and drivers for each segment, we discovered that the firm, for consistency’s sake, had a uniform pricing methodology, across all segments.

From the firm’s perspective, it was a purveyor of process equipment and it cost the same amount to produce the equipment, irrespective of the value in the industry it was sold. However, customers in different segments valued the “whole” product that the firm sold differently. One market segment placed value only on the core “device” while another market segment valued the device as well as the special services that the firm offered.

However, pricing was the same to both markets. Additionally, the competitive nature of the “commodity” market put extraordinary, downward pressures on pricing, which the firm unconsciously transferred to all other segments, sacrificing margins across all of them.

The firm rectified the situation by focusing on the high margin, specialty businesses and withdrew from unprofitable, low margin ones. Revenues and margins from profitable segments more than compensated the withdrawal from unprofitable ones. Additionally, the firm’s focus helped it immensely in reallocating and focusing scarce resources, and adding more value-added services to its core businesses for substantial competitive advantage and sustained growth, in a weak market.

Conclusion

These four avenues - taking advantage of positive trends in market drivers; rationalizing the product/service portfolio; improving pricing tactics, and increasing market share - catalyze each other, and create optimum conditions for accelerating short-term revenue growth, as well as instilling and setting the right organizational mind-set for long-term growth.OGFJ

The author

Pradeep Anand [[email protected]] is president of Seeta Resources [www.seeta.com]. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the oil and gas, technology, and engineering industries. Before founding Seeta Resources in 1993, he was vice president of marketing for Landmark Graphics, a division of Halliburton. Before that he worked for Sperry-Sun and Baker Hughes. Anand has an MBA from the University of Houston and a BS degree in metallurgical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay, India.