Special Report: Canadian royalty trusts provide high yields, affect transaction pricing

US firms doing business in Canada should have a thorough understanding of the tax advantages and other benefits of the uniquely Canadian income trusts.

Barry Munro, Warren Pashkowich, Ernst & Young, Calgary

Canadian income trusts have garnered both international headlines and investor interest because of their impact on transaction pricing (especially in Canada) and, not insignificantly, because of their often high-performing yields. And for any American firm operating in Canada, a thorough understanding of the unique Canadian income trust phenomenon is crucial if that firm wants to be successful in growing its Canadian business operations.

The proliferation and tax-advantageous nature of income trusts in Canada sparked a review by the Canadian government in the fall of 2005 of its tax policy toward trusts. And, while similar investment vehicles have existed globally, it is the acceptance by Canadian investors and the Canadian government’s tepid acceptance that income trusts are a fiscally responsible and legitimate means to conduct business that sets the Canadian trust model apart from its international counterparts.

Definition

A royalty trust is an income trust that derives substantially all of its income from the royalties earned on the net-profits of its subsidiaries’ production of oil and gas, and from the interest on high-yield debt with such subsidiaries. Unlike shareholders of corporations that are taxed on the distributed, after-tax profits of the corporation, a royalty trust “flows through” its income to its unit-holders so that it is taxed only at the unit-holder level (as ordinary income, dividends, or capital gains).

Generally, no tax is paid by the royalty trust on income it has distributed to its unit-holders. For non-Canadian resident unit-holders, income distributions from royalty trusts are subject to a 25% withholding tax, which may be reduced to 15% as a result of Canada’s tax treaties. As well, capital distributions are subjected to a 15% withholding tax.

As a result of the tax structure, Canadian taxable trust unit-holders avoid double taxation, Canadian tax exempt entities avoid tax completely, and US resident investors pay tax at a rate of 15%.

Origins

The first major royalty trust, which has evolved into the present day Enerplus Resources Fund, was established in 1985 and initially was anything but popular with the investment community. For one thing, by the spring of 1986, the price for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) had fallen to $11/bbl, dramatically reducing the amount of cash flowing from producing oil and gas properties.

There was also considerable skepticism among investors about the legitimacy of trusts, to the point that they were often thought of as sham vehicles. It was not until the mid-1990s that a significant proliferation of royalty trusts occurred, and in 1995 the first conversion of a corporation into a royalty trust was completed.

By the mid-1990s the perfect environment allowing for the proliferation of royalty trusts in the Canadian market was forming. Among the major factors supporting trust development was the maturation of the western Canadian sedimentary basin. The basin was ripe with long-term, stable, producing properties with little need for expensive exploration programs.

The large integrated producers saw limited upside in Canada and more attractive opportunities globally, so they began to exit or significantly reduce their investment in the basin. As part of the exodus, these companies sold their mature producing properties, and royalty trusts won substantially all of the property and corporate deals.

Royalty trusts, with their tax-favorable structure and support from the capital markets-and operating in an environment in which interest rates were declining significantly while trusts were paying cash on cash yields to unit-holders in the 15 to 20% range-were ideally structured to be aggressive and successful acquirers.

The dot-com bust in 2001, an historic low interest rate environment for several years, a sustained bullish market in commodity prices, and the tax effective structure of the trusts meant that oil and gas royalty trusts had become mainstream.

Current status

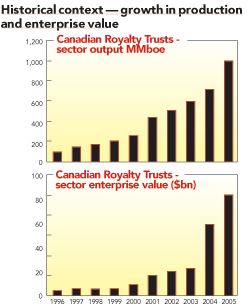

Today, Canadian oil and gas royalty trusts have a combined market capitalization exceeding $70 billion and in aggregate produce approximately one million boe per day-which is about one-sixth of total Canadian production. For many observers, it would be difficult to discern the difference between a conventional oil and gas company and a progressive royalty trust-except that the trusts would not typically re-invest 100% of their free cash flows into exploration and development activities and trusts are aggressive acquirers of existing producing properties using their strong equity as currency.

Most of the Canadian intermediate oil and gas sector is currently dominated by royalty trusts. Several of the senior trusts trade on the New York Stock Exchange (e.g., Enerplus, Enterra, Canetic, Pengrowth, Harvest, Baytex, PrimeWest, PennWest, and Provident) and trusts such as Canadian Oil Sands Trust and PennWest (following its proposed merger with Petrofund) have market capitalizations exceeding $10 billion.

Bluntly, oil and gas royalty trusts make the Canadian oil and gas business work. Junior exploration and production companies are well supported by the capital markets and are able to focus on higher growth opportunities. Trusts bring financial and operating discipline to the sector and thrive on mature properties. Trusts also provide an attractive exit option for the junior producers once they have achieved their growth objectives.

Impact on US firms

In the past two years, trusts have also provided attractive exits for US-owned enterprises operating in Canada. For example, both Kaiser Energy and Dominion Resources have liquidated a portion of their portfolios by way of sales to Canadian trusts.

In its simplest form, a trust conversion is structured as a fully leveraged buy-out by a new or existing mutual fund trust of a junior or intermediate producer, often coupled with the spin-out of a new junior oil and gas exploration company. The capital used to acquire the company is either raised through an offering of units by the mutual fund trust, or the company’s own stock is used as the currency to acquire units in the mutual fund trust.

Because there is generally no means by which a corporation can transact with a mutual fund trust on a tax-deferred basis, the conversion transaction is usually fully taxable to the shareholder. The internal leverage created through the conversion transaction is typically deeply subordinated and carries an interest rate typical of high-risk mezzanine financings. As a last step, a 99% net-profits interest royalty is then carved-out of the subsidiary’s producing properties.

The intent of the structuring, which in and of itself may be complex, is to create a cash flow stream from the oil and gas properties which is not subject to tax until ultimately in the hands of the trust unit-holders.

The question is often asked: Are oil and gas royalty trusts sustainable? The answer is, simply and loudly, yes.

The oil and gas business is a cyclical business and interest rates will not always remain at historic low levels. These factors add volatility to the trust sector but the progressive oil and gas royalty trust model is designed around managing the many risks associated with exploration and development activities, and are generally conservatively financed from a debt-leverage perspective.

Speaking to their stability, it is important to note that Canadian oil and gas royalty trusts enjoy wide-market acceptance and are strongly supported in the capital markets.

Recent trends

Most recently there has been a flurry of consolidation in the royalty trust sector with, for example, Starpoint/Acclaim; Harvest/Viking; PennWest/Petrofund; and Daylight/Sequoia all having announced mergers in just the past four months.

Another recent trend that appears to be gaining traction has Canadian oil and gas royalty trusts pursuing acquisition opportunities outside of Canada. Two of the best known examples are Vermillion Energy Trust with its oil and gas operations in France, and Provident Energy Trust with its operations in the US.

While Canadian trusts enjoy no tax advantage in completing on international transactions, they may enjoy a capital markets advantage given the strong valuations of their equity. In addition, the pursuit of foreign deals by Canadian trusts is also reflective of the acquisition metrics for, and availability of, deals at home.

At present, there is a very limited supply of acquisition opportunities in Canada and reserve acquisition metrics-on a per-barrel equivalent basis for both reserves and daily production in Canada-are among the highest on the planet. A collateral effect of the recent trust consolidation activity may well be an increased focus internationally given the increased size of Canadian trusts.

Increased scrutiny

Crucial to the continuing health of the trust environment is the question as to whether the Canadian government will eliminate the perceived tax advantages of income trusts. For much of their existence, income trusts have largely remained under the radar of Canada’s Department of Finance, but with success and rapid growth came scrutiny. However, to date, despite considerable political rhetoric, there has been no new policy pronouncement by Canada’s parliament concerning income trusts.

In late 2005, Canada’s Department of Finance did announce its concern with the tax leakage created by the trust structure and in response initiated a consultation process to review the issue. The government raised several questions-1) about whether traditional corporate structures would result in a lack of investment and a non-competitive business environment because trusts are in a position to outbid on deals using pre-tax valuations; and 2) about tax exempt entities and non-residents owning trust units and thus effectively paying no tax in the case of tax exempts, and just 15% in the case of non-residents, rather than the average federal and provincial tax rate of 46%.

In addition, proponents of trusts point out that the government’s current tax rules, which result in double taxation of corporate profits distributed to shareholders, have created the inefficient system and as such is really the model that requires refinement.

The taxation of income trusts remains an important tax policy and political issue, but one unlikely to be dealt with in the near term, given that a minority government holds power federally in Canada. It will take significant, sometimes controversial changes to the tax system to alter the perceived benefits trusts now enjoy, but, there appears to be no political will in a minority parliament to even broach the topic at this time.

The future of trusts

The number of income/royalty trusts traded on Canadian stock exchanges has grown dramatically over the past six years-from 57 trusts with an aggregate market capitalization of approximately $20 billion in 2000 to more than 240 trusts with an aggregate market capitalization of more than $170 billion today. As well, the trust model is now being successfully utilized in every possible business sector in Canada.

In the oil and gas sector, it is difficult to imagine a scenario where the trusts won’t continue to be an integral and dominant part of the industry. The trusts now establish many of the key benchmarks, such as valuations for existing producers and for acquisitions. And they now generally determine the growth and exit strategies for both junior companies and US-owned companies operating in Canada.

What about the future of trusts - will the model continue to evolve? Given the changing face of trusts over the past 15 years, it is a near certainty that the evolution of trust structures will continue to shift and adapt to new realities.

One other thing also remains clear: for US participants in the Canadian market - and increasingly for US companies trying to boost growth in their own backyards and secure US investor support - a thorough understanding of the structure and strategic drivers of Canadian oil and gas royalty trusts is essential if the benefits of these trusts are to be realized. OGFJ

The authors

Barry Munro[[email protected]] is an Ernst & Young Energy Center leader based in Calgary. Munro is office managing partner and leads Ernst & Young’s oil and gas practice in Canada.

Warren Pashkowich [[email protected]] is also an Ernst & Young Energy Center leader based in Calgary. He is a partner in the transaction tax practice and provides a particular focus on taxation as it affects deals in the oil and gas sector, including trust mergers, conversions, and reorganizations.