Refracking the shale plays

EXAMINING THE COMMERCIALITY OF RECOMPLETION

PER MAGNUS NYSVEEN AND LESLIE WEI, RYSTAD ENERGY

Refracturing of shale wells is a popular topic since operators can apply the latest technology to older wells, thereby increasing production without incurring all the costs of a new well. Well results indicate that the resources per well have doubled since 2012 for the main plays (See "Eagle Ford, Bakken, Permian," December 2015 OGFJ), making refracturing of shale wells a logical development. Operators are optimistically discussing the possibility of refracked wells in several different plays, but how have the results compared to expectations so far?

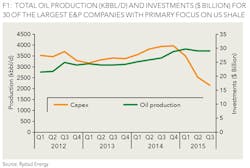

To refrac a well an operator goes into an old well, or underperforming well, stops the production and recompletes the well with new hydraulic stimulation. While this is not a new technique, its application to horizontal shale wells is still in the initial phase. As of August 2015, less than 1% of the total ~100,000 horizontal wells in the United States have been refracked. Figure 1 shows the number of USwells refracked each year split by play. Currently, the 2015 value is incomplete due to delays from state reporting, and the dotted line indicates the full year expected number. Compared to the overall drilling activity that decreased 40% in 2015, there is a clear interest in refrac opportunities as indicated by the concurrent 30% increase. There have been targeted refracks in almost all the plays, but the majority of the activity has been in Bakken, Barnett, and Eagle Ford. Furthermore, the chart only includes horizontal refrac jobs; there has also been a significant refrac campaign for vertical wells, Devon Energy, for example, refracked 150 vertical Barnett wells in 2015, where they report an average production increase of 700%.

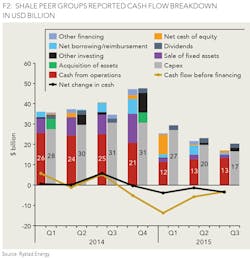

In theory, the cost of a refracked well should be similar to the cost of completing the well. On average, about 1/3 of the development cost of a horizontal shale well goes to drilling, while the remaining 2/3 is allocated to completion. This means, by refracking an older well, an operator can save the cost to drill the well. Currently, the Bakken is the play with the largest number of refracked horizontal wells. By examining the performance of the roughly 300 refracked wells, it is possible to quantify the success so far. Figure 2 shows the development of the production for the average Bakken well, one year before and one year after recompletion. The x-axis shows the cumulative months from re-frac, with month 0 representing the first month of production. On average, the process increases the production by more than four times after the new stimulation, with higher production throughout the entire first year.

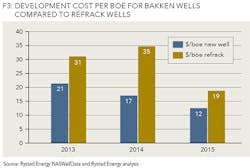

By comparing the additional production from refracs to the additional costs, it is possible to determine which method is more profitable. Figure 3 shows the development cost per barrel (EUR) for each well type. The values are based on the average capex per well, where the refrac wells incur 2/3 of the total well cost. State data and operator specific decline curves are used to determine the EUR. Since 2013, the average cost has decreased for both categories with the gap closing in 2015. If the trend continues, then refracks may become a more profitable approach for operators. It is also interesting to note that there is not one specific operator leading in the number of wells refracked, rather, approximately 30 operators are testing the method.

Refracking older wells definitely increases the recovery of the well, but given current results, it is generally more profitable for operators to drill a new well. Recompletion is still an immature recovery technique but once better results are replicable, refracked wells could hold potential for low cost production.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Per Magnus Nysveen is senior partner and head of analysis for Rystad Energy. He joined the company in 2004. He is responsible for valuation analysis of unconventional activities and is in charge of North American shale analysis. Nysveen has developed comprehensive models for production profile estimations and financial modeling for oil and gas fields. He has 20 years of experience within risk management and financial analysis, primarily from DNV. He holds an MSc degree from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and an MBA from INSEAD in France.

Leslie Wei is an analyst at Rystad Energy. Her main responsibility is analysis of unconventional activities in North America. She holds an MA in economics from the UC Santa Barbara and a BA in economics from the Pennsylvania State University.