The industry takes a hit

THE MIDSTREAM SEGMENT HAD THE SMALLEST DROP IN EQUITY VALUE, WHILE THE UPSTREAM AND OFS SEGMENTS FOLLOWED THE PRICE OF CRUDE CLOSELY

SEENU AKUNURI AND TIM STUHLREYER, PWC, HOUSTON

AT THE END OF 2014, US domestic energy companies had approximately $120 billion in goodwill and over $1.7 trillion in property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), and reserves on their balance sheets. The goodwill and other asset balances were the result of a vibrant transaction environment over the previous several years.

For those not familiar with the term goodwill, it is the residual amount of the purchase price after allocation to working capital, tangible assets, and identifiable intangible assets. The existence of goodwill is not necessarily an indication that buyers overpaid in these transactions, rather that the value paid in the transactions containing goodwill exceeded the value of identifiable tangible and intangible assets as of the closing date.

In many cases, goodwill is the result of differing commodity prices between what was used in the deal model to price the transaction versus what is used in the purchase price allocation; buyer-specific synergies or the growth expectations from new customers being acquired subsequent to a transaction from planned expansion, new service offerings, etc.

Driving the transaction activity mentioned previously were annual average Cushing WTI prices of $79 in 2010, $95 in 2011, $94 in 2012, and $98 in 2013. Even 2014, the year when prices began their steep decline, maintained a yearly average of $93. However, beginning in the second half of that year, the decline in oil prices led to the beginning of difficult times for the industry. The 2015 average Cushing WTI price was approximately $49 per barrel, representing a decline of $44 per barrel versus the 2014 average price. At production rates indicated by the EIA of 9.4 million boe per day in 2015, the $44 reduction in revenue per boe resulted in an overall loss of revenue of approximately $150 billion for the supply produced domestically, excluding the impact of any hedged production.

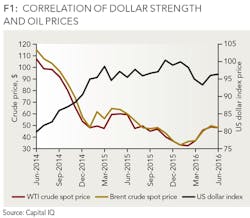

While the supply/demand imbalance is generally blamed for most of the decline in crude prices, the stronger US dollar also had an impact. As shown in Figure 1, the increase in value of the USD in 2014 coincided with the significant decline in oil prices.

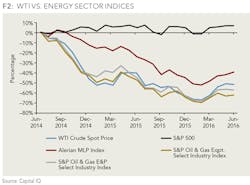

How has the downturn manifested itself in the equity markets? As illustrated in Figure 2, the stock price performance of these segments mirrored the performance of commodity prices over the observed time horizon. The midstream segment saw the smallest drop in equity value, as can be expected, while the upstream and services segments followed the price of crude extremely closely.

COST OF CAPITAL

While the impact of pricing alone was significant enough to drive impairments, another headwind for the industry was the impact to borrowing costs the distressed environment created. Many companies took advantage of rising prices during 2011 - 2014 by taking on significant debt to fund their operations. During 2015, when cash flow from operations was becoming insufficient to cover operations, companies requiring additional capital had trouble going to the equity markets due to depressed stock prices (see Figure 2) or the bond markets, which required significantly higher yields.

In December 2013, a BBB-rated energy company paid a yield on its debt of approximately 6.5%. However, by June of 2016, the same company would potentially have suffered multiple ratings downgrades leading to costs of new debt being substantially higher. Even considering a scenario where the company's rating was not downgraded, BBB yields reached as high as 9.6% in the first quarter of 2016. This meant that the same company was paying almost 50% more for new debt than in 2013. This coupled with the additional $200 billion in debt added to the balance sheets for these energy companies between December 2013 and June 2016 certainly served to exacerbate the problems for the industry.

GOODWILL AND ASSET IMPAIRMENTS

While many energy companies reacted quickly to the price adjustments by attempting to remove excess costs from operations, this significant decline in revenue contributed to asset/goodwill impairments for the industry. The decline in commodity prices has a direct impact on upstream companies. However, the impact is not confined to those companies, rather it flows through the industry.

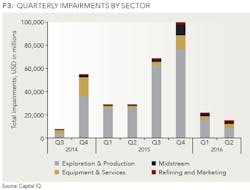

As can be seen in Figure 3, the most significant impairments took place in Q3 and Q4 of 2015. Multiple factors contributed to this, chief among them are the reduction in hedges for upstream companies as there was reluctance to hedge at prices that appeared to be depressed; the fact that many full-cost companies were testing for impairment in previous quarters with SEC pricing that still reflected higher 2014 prices until Q2 of 2015; and the fact that Q3 and Q4 of 2015 represented significantly reduced quarterly average prices for crude oil.

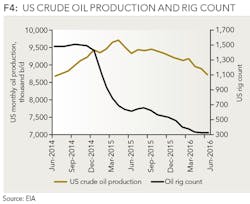

The reduction in prices caused upstream companies to reduce capital budgets that directly impacted equipment and services companies as rigs became idled. Enhancing this problem was the seemingly positive development of improvements in well productivity, illustrated in Figure 4. This meant that even as drilling was curtailed and less new wells began producing, production levels were able to be maintained continuing the supply pressure placed on prices. This trend has begun to reverse itself as continual declines in production ultimately lead to rigs being brought back online to maintain or increase production.

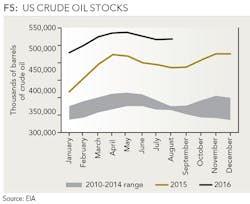

As illustrated in Figure 5, the historic production levels have created crude oil stocks significantly higher than those seen in the years 2010 to 2015. These inventory levels have also contributed to the pressure on crude prices.

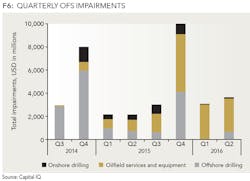

DRILLING IMPAIRMENTS

We note that while upstream companies were impacted the most, next in line were the services and equipment companies. Within this segment, offshore drillers were impacted the most, as evidenced in Figure 6. Primary contributing factors are project length and required capital outlay for offshore projects. As upstream companies "high graded," these types of projects were the first to be eliminated. Consequently, demand for offshore drilling suffered.

Further evidence of the difficult environment offshore drillers have dealt with is the available data related to day-rate declines. Offshore drillers suffered declines of approximately 15% to 20% in day-rates from July to December 2014; and additional 35% to 40% declines from the December 2014 day-rate to December 2015. The overall decline of approximately 45% from July 2014 rates has proven too much to bear for several offshore drillers as multiple companies have sought protection through bankruptcy.

WHAT'S NEXT?

While companies within the energy industry have suffered significant impairments between the recent commodity peak of mid-2014 and trough of early 2016, they still hold substantial goodwill, PP&E, and reserves on their balance sheets. From the peak, year-end highs in 2014 of about $120 billion in goodwill and $1.7 trillion in PP&E and reserves, these values have declined to $96 billion in goodwill and $1.5 trillion in PP&E and reserves as of June 2016. While the declines of $24 billion in goodwill and $200 billion in PP&E and reserves are substantial, they represent approximately 20% of goodwill and 10% of PP&E and reserves. This versus declines of over 50% in commodity prices indicates many of the transactions that led to the goodwill and PP&E and reserve balances occurred at less than the peak market prices.

The substantial balances can be seen as an indication of stability within the industry; however, they also leave the industry potentially exposed to further impairments as WTI averaged around $40 for the first six months of 2016. If prices stay below the $50 mark, it could have a significant impact on the industry. At this price, upstream companies with high leverage and high cost structures will need to consider a course of action including continuing to rationalize their cost structures and possibly divesting assets to improve their balance sheet or meet cash flow requirements.

Oilfield equipment and services companies that have deeply discounted their offerings may see little uptick to a more historical price level in the immediate horizon and will also need to examine their balance sheets and costs structures for sustainability. Additionally, midstream companies may be forced to renegotiate the take or pay terms of their contracts with clients in or contemplating bankruptcy.

Companies already in distress will need to make decisions related to their next steps. The options available to them include: joining the growing number of energy companies that have filed for bankruptcy protection during this downturn, merge or get acquired by a stronger entity, or tighten their belts and continue operating as a standalone company.

Each decision carries with it important steps to ensure success. Prior to filing for bankruptcy, companies should seek the advice of specialists in this area to create a "prepackaged" bankruptcy plan leading to a short time in bankruptcy. Companies seeking to merge or be acquired should also seek qualified assistance in determining the right merger or acquisition partner. Simply having a strong balance sheet should not be all that is required when culture, operating structure, and product line fits, among other variables, are vital to the success of the combined entity.

Finally, the potential for survival while operating as a standalone company can be greatly improved by examining operations and jettisoning non-core operations while also maintaining an eye on the market for opportunistic acquisitions. One thing that can be counted on is that the longer the downturn lasts, the more assets that will become available for those companies with strong enough balance sheets to capitalize on the opportunities.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Seenu Akunuri is a principal in PwC's deals practice and has nearly 20 years of experience in the valuation of businesses and assets focusing on the energy industry. He has consulted with clients on complex valuation issues around structuring, buy-side, sell-side, tax and financial reporting purposes. Akunuri holds an MBA with a concentration in finance and accounting from Tulane University.

Tim Stuhlreyer is a director in PwC's deals practice based in Houston. He has 11 years of experience performing business and asset valuations and focuses his work on the energy industry. Stuhlreyer is a frequent speaker on the topic of energy company valuation and is a vice chair of the Houston CPA Society's Energy Committee. He has an undergraduate degree in industrial engineering from Texas A&M and an MBA from the University of Texas.