Shale players must adapt a new norm

CHANGING PRICE ENVIRONMENT IS FORCING MANY TO STREAMLINE, INVEST IN IT, AND BECOME MORE EFFICIENT

HERVE WILCZYNSKI, ERNST & YOUNG LLP, HOUSTON

JENNIFER BLAESER, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BOOTH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, CHICAGO

THOMAS THAYYIL, ERNST & YOUNG LLP, HOUSTON

THE SHIFT from oil scarcity to abundance is happening at a unique time in the history of the oil and gas industry. For the first time in over 100 years, market forces are truly setting the oil prices, in the process dashing any hope for a traditional V-shaped recovery. In this post-Seven Sisters and OPEC era, shale players find themselves in the role of short-cycle producers. Superior operating performance and ability to rapidly ramp production up and down are becoming key differentiators. So how can shale players of all sizes adapt to this new norm?

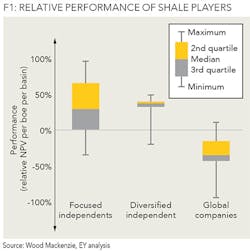

Some companies already have a head start. EY recently looked at the relative performance of the top 100 US shale players and identified the ones that manage to best realize the potential of their reservoirs. Three distinct groups emerge (see Figure 1). The companies operating in one or two basins define the top quartile performance of the industry. Larger, diversified independents achieve a more consistent level of performance but fail to reach the top level set by some of their smaller peers. Global companies still have a lot of work to do to adapt to the fast-moving environment that characterizes the exploitation of unconventional resources.

The difference between small and larger organizations is actually not that surprising. Cross-industry examples show how smaller players can become successful but eventually start to experience some of the challenges of their larger competitors. For example, Frederic Laloux, in his book Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness, argues that large organizations often converge toward centralized, top-down governance models with heavy reliance on formal processes. This "mutation" too often results in loss of employee engagement and corporate inertia. In contrast, innovative models based on concepts such as self-management and distributed structures help preserve the focus of the front line on innovation, performance and agility. These help large organizations put some spring back in their step and achieve superior business performance.

These learnings from complex organizations across industries are quite relevant for large US independents. The sector experienced spectacular growth after the late-'90s wave of mega-mergers. Each company built its success around a set of critical capabilities. These varied across organizations. Some were very good at making deals and growing via acquisitions or aggressive land moves. Others used technology and superior geoscience capabilities to identify better rocks.

All of these companies shared common business themes: they made decisions quickly, were not afraid to take technical and business risks, and had a "can do" attitude. As they grew in size and complexity, many of the organizations implemented more formal processes, built central functions, and deployed more robust IT systems to increase consistency of execution and capture economies of scale. As a result, the larger independents became slower at entering new basins, reducing development costs, and optimizing production when developing new plays. In other words, smaller players made better decisions, faster.

Could the solution be to reverse this trend and go back to purely asset-based organizations? Probably not, as the data in Figure 1 show that a group of assets operating independently typically experiences a higher variability in terms of performance. Moving away from the binary debate between centralization and decentralization, some players are emulating some of the cross-industry innovators to rebuild the fast-paced, innovative frontline dynamics that fueled the growth of the sector. These innovative ideas impact multiple aspects of a business model:

The unconventional way of doing things: Efficient processes to execute routine new development activities have become table stakes for shale operators. Extensive lean programs have helped reduce costs and compress cycle times, making shale plays extremely resilient to the current volatile market conditions. However, stark differences emerge between companies on the management of non-routine activities such as application of new technologies, adjustments to the drilling plan when subsurface conditions evolve, or investment in new acreage. Being able to make fast decisions in a rapidly changing environment is a hallmark of unconventional plays, and this is not a strong suit of the oil and gas industry. In fact, large investments in conventional plays usually benefit from lengthy decision cycles to avoid rushing into uncertain situations, typically done by central organizations. The capital planning process is an example where the "unconventional way" pushes the tactical decisions down to the assets to increase agility, with the proper escalation mechanisms to address major changes in a field development plan. The process is supported by an integrated IT infrastructure that enables effective cross-functional planning and provides a quasi-real-time view on actual performance. In this model, asset teams have full latitude to change the drilling program within the boundary of an AFE, experiment with various technologies, choose well designs, decide on well interventions, manage suppliers and make recommendations for modification to the capital investment program. These teams are also accountable for their performance and assessed against a set of metrics that provide the right incentive to not only increase production and reduce cost, but also improve the deployment of capital across various assets.

The type of expertise and its deployment: The profile of the petro technical staff is also a key factor that impacts the speed and quality of technical decisions. Different strategies around the development of technical talent exist. The first, based on developing specialists with intimate knowledge of a reservoir or specific technologies, tends to exist in smaller organizations. Other strategies, based on the development of multi-skilled staff, are usually preferred in larger organizations where needs and opportunities are more diverse than in smaller companies. With the second approach, it can take up to an average of seven years to develop an experienced petro-technical person, two to three years longer than the specialist model can accomplish. Leading independents tend to mix the two models by focusing highly experienced staff, potentially external hires, with specific basin knowledge while implementing a very structured mentoring program to accelerate the development of less experienced employees. This approach, similar to what the health care industry has adopted, is a key enabler for the model previously discussed where tactical decisions are made quickly in the assets. This raises the question: what is the role of the central functions and, therefore, what needs to be centralized? Some companies are taking a reservoir back view and identifying the critical skills that need to be close to the asset. These capabilities include roles such as permitting, land management, reservoir engineering, completion engineering, drilling, production management, HSE and supplier management. Central functions typically focus more on assurance tasks (e.g., reserve reporting, audit), scale-sensitive activities (e.g., financials) as well as the acceleration of learning across assets. For example, drilling operations typically follow a set of well-established processes that the asset teams execute. In short, the industry is moving toward a distributed model, as an alternative to the asset vs. centralized ones, to bring deep expertise as close as possible to the assets, while focusing the role of central function to cross-assets learning acceleration or assurance roles.

The end game is to preserve the culture: Work practices, technical expertise and organizational structures are all transferable from company to company. What is not transferable is the culture, and this is what usually makes the difference between good and great operators. Large US independents need to preserve what made them successful. It will vary by company, but in general the sector became successful by taking risks, knowing how to quickly learn from mistakes and having a shared desire to succeed within an organization. These traits can be eroded as organizations become larger, more process-based and less reliant on interpersonal connections. This is where the role of senior management becomes critical to set the right tone and culture. For example, few companies successfully made the switch from natural gas to oil production when indication of oversupply started to loom after 2005. This was a bold move at the time, but successful organizations saw an opportunity based on their technical capabilities ahead of the competition and stayed the course, entering at steep discounts the "oily" basins that would drive the resurgence of US onshore oil production. Fast moves do not always pay off, and being able to fail quickly is also a very important cultural aspect of leading independents. For example, rapid qualification is how new technology is introduced in support of the operations. Technology drove the scaling-up of shale plays, and they continue to play a very important role. Subsurface characterization, completion design and water usage are all examples of active research areas. The traditional centrally managed R&D processes structured around decision gates are ill-equipped to deal with the need to deploy technology fast. New models focused on achieving concrete improvements are emerging to rapidly evaluate new technologies. These models work only when the failure of a technical solution is viewed as a source of learning instead of a wasted opportunity. Here again, the role of the assets as an innovative engine is critical.

The majority of shale players have made significant progress over the years by streamlining efficient frontline processes, building central technical capabilities, and investing in IT infrastructure and data management capabilities. The integration of these various elements to form a high-performance business model can be a challenge in larger organizations. The changing pricing environment is a strong catalyst for companies to further integrate the different parts of their business model to achieve the next level of operational excellence.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Herve Wilczynski is a principal at Ernst & Young LLP. He has over 20 years of experience across the oil and gas value chain and has held senior management positions with global oilfield service companies and general management consulting firms. He is experienced in broad strategic and operational issues in the energy sector.

Jennifer Blaeser is a senior associate director at The University of Chicago, Booth School of Business. She has held senior-level positions with Fortune 500 companies and blue-chip consulting organizations, and consults with executives across a variety of industries on organizational effectiveness issues.

Thomas Thayyil, senior manager at Ernst & Young LLP, also contributed to this article.

The views reflected in this article are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organization or its member firms.