New methane regulations

EVEN WITH HIGHER COSTS, EPA CLAIMS AN ECONOMIC BENEFIT FROM NEW RULES

LARRY W. NETTLES, VINSON & ELKINS LLP, HOUSTON

CORINNE V. SNOW, VINSON & ELKINS LLP, NEW YORK

THE US Environmental Protection Agency's first-ever rule to directly regulate methane emissions from the oil and gas sector went into effect on August 2. At a time when the industry is already feeling the pinch from low oil and gas prices, this rule adds yet another financial burden on upstream and midstream operations. Indeed, EPA now estimates the costs of complying with the rule, known as Subpart OOOOa, or Quad Oa, to be significantly higher than its initial estimates in the fall of 2015.

Despite these increased costs, EPA has concluded that the rule will have a net economic benefit. To reach this result, EPA used an economic metric to assign a high-priced financial benefit for every ton of methane emissions that the rule will prevent.

MarkWest photo

COST ESTIMATES

EPA's new rule expands air regulations that previously applied to natural gas well sites and processing plants to cover additional equipment and operations, including at certain oil well sites and midstream compressor stations. The new rule has two main parts: (1) requiring that certain control devices or practices be used to reduce methane and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from regulated equipment and during well completions, and (2) implementing leak detection and repair (LDAR) programs to prevent natural gas leaks at well sites and compressor stations. The rule only applies to well sites, compressor stations, natural gas processing plants, and certain equipment that is new or has been "modified" or "reconstructed" since Sept. 18, 2015.

When EPA proposed Quad Oa in September 2015, the agency stated that the rule would cost the oil and gas industry between $170 to $180 million in 2020 and between $280 to $330 million in 2025. When it released the final rule, EPA raised its estimates of these total industry-wide capital compliance cost of significantly. EPA now estimates the total capital cost of the final rule will be $250 million in 2020 and $360 million in 2025. EPA also raised its estimates for the annualized engineering costs associated with the rule, from an estimated $180 to $200 million in 2020 and $370 to 500 million in 2025, to $390 million in 2020 and $640 million in 2020.

The rule will grow more expensive with time because all well sites, compressor stations, gas processing plants, and regulated equipment that the industry adds from here on out will be subject to these regulations. Likewise, as operators make certain changes to their existing equipment and facilities, those facilities will also be subject to the new rule.

When broken down further, EPA's analysis indicates that the rule's costs will be felt more heavily by the upstream segment of the industry. EPA estimates that the largest portion of capital costs will result from companies meeting the rule's new well completion requirements. For certain wells, Quad Oa requires owners and/or operators to use reduced emission completions (also referred to as "RECs" or "green completions") to reduce methane and VOC emissions. These RECs must be used in combination with a combustion device-such as a flare or combustion control device-to prevent emissions. During certain phases of flowback, operators must route all salable gas from a separator to a flow line or collection system, re-injected it into the well or another well, use it as an onsite fuel source, or use it for "another useful purpose that a purchased fuel or raw material would serve."

For requirements such as these well completion rules, which force companies to capture natural gas that would have otherwise been vented to the atmosphere, EPA assumed that companies will be able to sell the recovered gas. EPA then reduced its estimated compliance costs by the revenues that EPA estimates operators will receive from selling this recovered natural gas. In total, EPA estimates that operators will recover about 16,000,000 million cubic feet of natural gas in 2020 and 27,000,000 mcf in 2025 as a result of Quad Oa.

Despite the fact that natural gas prices have remained below $3/mcf for more than a year, EPA assumed a wellhead natural gas price of $4/mcf for the sake of its revenue calculations. EPA acknowledged that there is geographic variability in wellhead prices, which can influence estimated engineering costs. In fact, by EPA's own calculations, a $1/mcf change in the wellhead price would change its estimated engineering compliance costs by about $16 million in 2020 and $27 million in 2025.

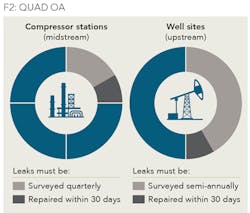

The second greatest cost associated with Quad Oa comes from implementing the rule's LDAR program and making the changes required for pneumatic pumps. The LDAR program is also expected to account for the largest portion of the engineering costs. Under the LDAR requirements, operators at new, modified, or reconstructed compressor stations must conduct quarterly surveys using one of two leak detection methods and then make repairs to any leaks within 30 days. Operators have an additional 30 days from the time of repair to verify that the leak has been fixed. The LDAR requirements for well sites are almost identical to those for compressor stations, except that the surveys only need to be conducted semi-annually, as opposed to quarterly.

Finding qualified employees or contractors to carry out these programs will be no easy task, particularly for upstream operators whose well sites are in remote locations and dispersed over large geographic areas. By 2020, EPA anticipates that the Quad Oa well completion requirements will affect nearly 13,000 oil wells, and the LDAR requirements will affect 94,000 well pads. In contrast, the LDAR requirements are only expected to impact a few hundred compressor stations.

CALCULATING BENEFITS

Despite these high industry-wide costs, EPA concludes that Quad Oa will have a net economic benefit. Important to this conclusion is the fact that EPA is regulating methane as a greenhouse gas (GHG). In the past, EPA's GHG regulations have focused on cabon dioxide (CO2), but EPA considers methane to be a far more potent GHG, and explains in the preamble to Quad Oa that methane has a 100-year global warming potential that is 28-36 times greater than CO2.

Global warming potential is a measure of how much additional energy the earth will absorb over 100 years as a result of emissions of a given gas, and is measured in CO2-equivalency. EPA's logic is essentially this: by reducing costly future climate impacts, this rule results in a long-term economic benefit that outstrips the costs to the industry. However, unlike CO2, which can persist as a GHG in the atmosphere for more than 100 years, methane released into the atmosphere is converted to non-GHG gases within 12 years.

EPA estimates that Quad Oa will reduce methane emissions by the equivalent of 6.9 million metric tons of CO2 in 2020, and the equivalent of 11 million metric tons of CO2 in 2025. EPA then used a model known as the Social Cost of Methane to determine that every ton of methane emissions that this rule prevents was worth $1,100 in present dollars. As a result, EPA estimate that the methane-related monetized climate benefits of the rule will be $360 million in 2020 and $690 million in 2025 using a 3% discount rate. EPA estimates that the majority of these emissions come from repairs to gas leaks in equipment under the LDAR program, followed by reductions from oil well completions and recompletions.

For several decades, economists have been trying to develop a model that can accurately place a present-dollar value on projected future benefits to the climate from reducing GHG emissions. In theory, such a model could capture all of the changes, both positive and negative, that each additional unit of GHGs would have on various regions of the globe and result in a single monetary value for the impact of a unit of emissions.

In the past, EPA and other federal agencies have used a similar model called the Social Cost of Carbon to value reductions in CO2. While the Social Cost of Carbon metric has faced plenty of criticism of its own, it is still far more established than the Social Cost of Methane metric. As EPA explained in the proposed rule, the federal interagency working group that developed the Social Cost of Carbon model has not yet issued figures or guidance on how to value methane emissions. As noted above, methane and CO2 also act differently once they are released into the atmosphere, and economists who work with these metrics have noted that these differences make it difficult to accurately translate impacts of methane based on their "CO2-equivalents" in an economic analysis.

Critics of these models argue that it is very hard to accurately determine what impacts will occur hundreds of years in the future, and that it is difficult to determine the appropriate discount rate when trying to consider such impact in present-dollar terms. The idea of discounting is based in economics: we assume that people put more value on a benefit they receive today, than an identical benefit that they will not receive until the distant future. Guidance from the Office of Management and Budget instructs federal agencies to discount "[a]ll future benefits and costs, including non-monetized benefits and costs."

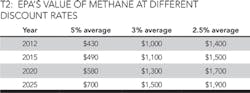

EPA employed a 3% discount rate to calculate the benefits of Quad Oa using the Social Cost of Methane, while simultaneously using a seven-percent discount rate to calculate the costs of complying with the rule. Because climate models like the Social Cost of Methane predict impacts far into the future, a small change in the discount rate can result in large increases or decreases in the estimated value of reducing a unit of GHGs today.

Table 2 shows the Social Costs of Methane values used by EPA at different discount rates, and demonstrates how greatly the value placed on a single ton of methane can change by slightly altering the discount rate. According to estimates in a presentation by the American Enterprise Institute, the present value of reducing a ton of CO2 emissions at a 7% discount rate becomes small or even negative. While EPA did not include a calculation of the Social Cost of Methane at a 7% discount rate, one group estimated that at the 7% percent rate, a ton of methane would only be valued at $212.

By placing such a high price on each ton of methane emissions that the rule reduced, EPA was able to calculate an economic benefit from Quad Oa that dwarfs the high compliance costs that the industry will face.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Larry W. Nettles is a partner in Vinson & Elkins' Houston office. As head of V&E's Environmental and Natural Resources Practice Group, Nettles advises clients facing multifaceted environmental problems, such as those frequently encountered in large business transactions. He has extensive experience with counseling, permitting, and civil and criminal litigation. Nettles serves as co-chair of the firm's Energy and Infrastructure practice group and as chair of V&E's Shale and Hydraulic Fracturing Task Force. He is also a member of the firm's Climate Change practice group.

Corinne V. Snow is an associate in Vinson & Elkins' New York office. Snow's principal area of practice is environmental law, with an emphasis on transactional environmental issues, regulatory compliance, and enforcement defense. Her other practice areas include climate change, environmental litigation, and emergency response to environmental accidents.

This article is intended for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or services. These materials represent the views of and summaries by the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Vinson & Elkins LLP or of any of its other attorneys or clients.