Market development in Argentina

Is Vaca Muerta competitive in today's market?

KJETIL SOLBRÆKKE AND BIELENIS VILLANUEVA TRIANA, RYSTAD ENERGY

IT HAS BEEN ACKNOWLEDGED by the oil industry for a long time that Argentina has one of the most promising shale plays in the world - the Vaca Muerta shale play in the Neuquen Basin. It is also the most developed shale play outside of North America. The shale boom that many expected in this play has not yet happened, even though there seems no doubt that the Argentina shale resource will continue to be developed in the years to come.

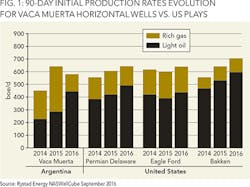

Looking at well productivity of the Vaca Muerta, the initial rates from its horizontal wells are comparable to major shale plays in the US, as depicted in Figure 1. These production rates confirm the competitive deliverability of the Vaca Muerta horizontal wells, even though only approximately 150 of them have been drilled to date. The gas content on Vaca Muerta wells is significant and it varies depending on the hydrocarbon window were they are drilled. In general, these wells have a significant content of rich gas, even in the oil window.

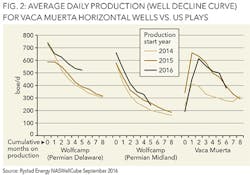

Together with competitive initial rates, Vaca Muerta wells have also shown lower initial decline rates than similar wells in the US, as shown in Figure 2. This figure also shows the choking (restricted flow) performed in the Vaca Muerta wells during the first 1-2 months of production.

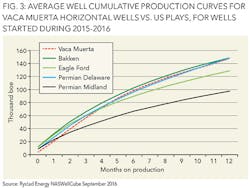

The lower decline experienced in the Vaca Muerta wells eventually leads to higher ultimate recovery, as shown in Figure 3. After 4-5 months on production, a Vaca Muerta well already produces more volumes than a similar well in the Permian Midland or the Eagle Ford. After 12 months on production, a Vaca Muerta well produces similar volumes to a well in the Bakken or the Permian Delaware.

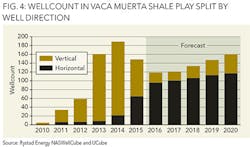

Even though the focus in the Vaca Muerta is currently on horizontal drilling, 82% of all wells drilled to date are vertical after a dedicated drilling program performed by YPF in the play. Future vertical drilling will be limited to pilot and exploratory projects, while development drilling is expected to be done with horizontal wells, as shown in Figure 4. YPF, as the dominant operator in the Vaca Muerta, confirms this with a development plan focused on horizontal wells. Future development will also be encouraged by higher natural gas prices as agreed by the government for all natural gas from "new sources" (mainly tight and offshore development) to 6.5-7.5 USD/kcf, which is similar to the price currently paid for imported gas from Bolivia. This is an important factor because such gas price in Argentina is much higher than what the American shale companies can expect at Henry Hub.

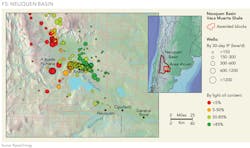

Together with excellent well results and high gas prices, another advantage to shale development in the Neuquen Basin is the topography of the area and accessibility to water. The area consists of dry sandy plains easy to prepare for PAD drilling and is located between to large rivers (Figure 5).

Even though it has several advantages, shale activity in the Vaca Muerta is still limited by high costs. Several local and foreign operators have tried to invest, but ultimately closed down and sold assets-mainly to YPF, which was the case for Oxy, Pioneer, EOG, Apache and Medanito.

When looking at the above ground risk and challenges, one is sand or proppant. Proppant is a key material that is not yet found locally. It must be imported together with equipment such as drilling rigs, pipes, valves, etc. and transported to drilling sites, some of which are located relatively far (2-3 hour drive) from populated areas. All this brings up the first important setback in the area: logistics.

Despite water available in the shale play area, it must be transported to the various drilling sites. Today there are no pipelines or railways to transport water, which means every gallon of water must trucked to the site. It takes approximately 120 trucks to transport sufficient water to frac one well. In addition, sand or proppant must be transported together with equipment and personnel. The logistical challenge is enormous and a plan, including considerations for piped water and railway systems, has to be put in place. Without these investments, activity will be limited by logistical barriers and efficiency will not increase sufficiently because of a lack of economies of scale.

Given these limitations, the costs per well in Neuquen are in the range of 2-3 times the cost of a similar well in the US. For instance, the cost of the pilot horizontal wells currently drilled by operators less experienced than YPF are obviously more costly because of the ambitions of gathering data, coring and increasing the knowledge of the stratigraphy in the area. However, the cost breakdown shows higher costs in all sequences of the operation than what is seen from wells drilled in the US. The lowest cost for horizontal wells in Neuquen was indicated down to approximately US$6 million for the drilling and about US$4 million for the completion. This cost breakdown between drilling and completion is interesting because, for wells in the US, 60% of total cost is linked to completion, and 40% is linked to drilling. The higher drilling costs experienced in Argentina compared to the US are related but not limited to:

- Cost of accessing equipment and materials, which must be imported

- Higher number of crew members needed per rig (as required by local unions)

- Regulations requiring dry locations (no fluid should touch the ground, so mud pools are not allowed, all fluids need to be tanked), and other regulations regarding HSE and psi requirements on the equipment

- Some operators using oil-base mud instead of water-base

- Collapsing of casing

- Presence of some high-pressure formations such as Quintuco which still need to be drilled up before reaching the Vaca Muerta, hence increasing the drilling time per well.

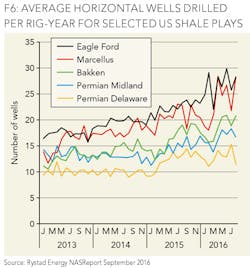

The above observations limit the number of horizontal wells drilled per rig-year to only nine in Argentina, compared to up to 30 wells per rig-year in the Eagle Ford in the US, as shown in Figure 6. The acceleration of pad-drilling use can also increase the drilling time in Argentina. Currently, wells are drilled, completed, and connected one by one instead of using the pad-method, mainly because operators prefer to bring each well to production as soon as possible instead of waiting for several wells to be drilled, completed, and brought online together.

An important factor to shale development in Argentina is politics. This includes federal import taxes, local authorities, labor unions and general relationships between service suppliers and the community. Since a special import tax is currently applied, equipment imported from the US will be at least 20-30% more expensive in Argentina than in the US. Without any changes in the policy regarding importation, the best wells in Neuquen could still end up 50% more expensive than those in the US. Regarding local authorities and labor unions, these regulate the activity quite rigorously. Labor unions require more workers per rig than in the US, so in spite of salaries being lower in Argentina, manpower costs are higher than in the US. Regarding local service suppliers, they represent a significant force behind the activity according to their capability and capacity to supply the operating companies. After meeting personally with some of the key local suppliers, the general impression is that there is a lot of local knowledge and capability, but the capacity needs to increase substantially in order to deliver on an activity increase. Many of the local suppliers lack long-term development commitments from the operators and perhaps certainty for political stability. If the operators and suppliers can demonstrate that projects with larger scale will take place, it is assumed that the unions will become more flexible because many more jobs will be created and a stronger trust sentiment will be created among workers, suppliers, and the community.

Summarizing, the impression on the Neuquen is that there is some capacity in place ready to start the shale revolution in Argentina. Rystad Energy believes that Vaca Muerta has excellent opportunities to become a significant shale play in future. With a total acreage of 30,000 square kilometers, as many as 50,000 wells could be drilled in the area. A portion of the oil and gas produced could potentially be piped to Chile, offering relatively easy access to export markets. The potential for optimization is huge, but so is the need for investments. More rigs are needed, more roads are needed, railway logistics are needed, local pipelines for transportation of water are needed. Most of all, a road map of a grand plan for the development of the resources in Vaca Muerta is needed.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kjetil Solbrække is head of Rystad Energy's Brazil office in Rio de Janeiro. In Brazil, Solbrække has held several management positions, including CEO for Panoro Energy and general manager for Norsk Hydro. Before moving to Rio de Janeiro, Solbrække worked at Norsk Hydro in Oslo as CFO and SVP for International Business Development for 10 years. He started his career at the Ministry of Petroleum in Norway as an economist from the University of Oslo.

Bielenis Villanueva Triana is a senior analyst at Rystad Energy. Her focus is on shale asset valuation. She is a project manager for North American Shale, with five years of experience in forecasting production, reserves and economics of shale assets globally. Bielenis holds a MSc in Petroleum Engineering from the University of Oklahoma, USA, which included two years of experience in simulation of reservoir performance.