The Islamization of project finance in the Gulf states

Justin Dargin, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

The sub-prime crisis raging throughout the developed and developing world as of yet shows no sign of abating. This crisis provoked a fearful flight from the more boutique asset classes, such as the highly collateralized debt obligations that precipitated the financial storm. While Islamic financial instruments currently make up a small proportion of global finance, they actually experienced an annual 15% growth from 2005 to 2008 (Fig. 1), with the energy-producing Gulf nations in the Middle East responsible for much of the increase.

Several factors spur this intensification: the escape from the more esoteric highly-leveraged financial assets, and the rise in per-capita wealth of the Gulf and Asian Islamic nations. The spectacular growth by many of the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) nations promoted the sukuk, the Islamic bonds that have been the fastest-growing element of the Islamic financial market. The highly coveted sukuk market reached $97.3 billion in 2007, with the Gulf states and Malaysia being the largest regional investors.

The Gulf countries, with their massive potential liquidity, tied up in approximately $3 trillion of sovereign wealth funds, are the logical next stage towards Islamic financing of major regional projects. The use of Islamic finance to underwrite large-scale energy projects in the Gulf is a fairly new phenomenon, and has few precedents. International lenders utilizing traditional financial instruments have historically dominated the big energy infrastructure projects in the Gulf region. GCC governments selected US, European, and Japanese banks for a multitude of reasons, most notably:

- Lower transaction costs related to their in-depth expertise of project structuring.

- The ability to provide the billions of dollars necessary for these scale projects.

- Western financial institutions had political leverage with their own governments, which empowered the banks to act as the intermediaries between large Western oil and gas companies and the GCC host states.

In the face of this entrenched influence, Gulf banks were, for decades, treated dismissively or plainly ignored in mega-billion dollar energy investment deals. Gulf banks, therefore, found solace with the “crumbs” of the large-scale transactions, such as short-term finance deals and bridge loans. However, that environment has changed qualitatively, to the point that Islamic loans now take a larger allocation of local energy projects, alongside the more active regional banks.

However, to understand why Islamic finance holds an attraction in the Gulf region, a few basic points must be clarified. The term “Islamic finance” refers to transactions under Islamic legal (or Shari’ah) principles, based on the Muslim holy book, the Qu’ran, and the Sunna, the sayings and attributes of the Prophet Muhammad. The core of Islamic finance is the prohibition and shunning of usury (Arabic-Riba) and speculative enterprises. The Gulf region, which is dominated by the Sunni branch of Islam, naturally gravitates towards financial structures that accord with their ancient beliefs.

Dolphin Project

The Dolphin Natural Gas Pipeline Project (Dolphin), which exports natural gas from Qatar’s enormous Northfield to the ravenous, energy-starved economies of the United Arab Emirates and Oman, established a precedent for regional bank participation and Islamic financing of energy projects. Dolphin proved that regional banks are able to be involved quite significantly in multi-structured tranches and project development from the beginning.

The primary company behind Dolphin, Dolphin Energy Ltd. (DEL) structured the financing as a cocktail of traditional and Islamic instruments. A consortium of 25 banks provided conventional and Islamic project financing, which altogether totaled $3.45 billion. Of this, a $1 billion tranche was comprised of Islamic instruments, specifically Istisna’a — led by an amalgam of five international banks and two regional financial institutions. The Dolphin project broke the trepidation that held that large-scale Islamic finance could not succeed for a project of this scope; bankers had been skeptical about whether DEL had the ability (and credibility) to raise the necessary capital, while Shari’ah scholars initially questioned whether an advanced rental payment could be linked to a floating rate, instead of a fixed one. The scholars eventually concluded that a floating rate could be used in a manner consistent with Qu’ranic injunctions.

In general, financing may be Shari’ah compliant if it is either Istisna’a—a forward lease of assets not yet in service—or Ijara, essentially the sale and leaseback of operational assets. Dolphin has the distinction of being the first utilization of Islamic financing for the upstream portion of project funding, which has traditionally been the most difficult to justify in the Shari’ah context.

Other high-profile projects

After the noted success of Dolphin, several other high-profile, Islamic-backed energy deals were concluded. In July of 2006, Saudi Basic Industries Corp. (SABIC) announced a sukuk issuance totaling approximately $800 million. Although demonstrating a clear preference for Western financial institutions, Saudi officials announced that HSBC Group would be the lead manager and book runner for the issuance. The SABIC sukuk issuance established a domestic benchmark of sorts, as it was the first to take place under the Kingdom’s fairly new Capital Markets Law (promulgated 2006), which codified and clarified the legal status of Islamic finance. It was also Saudi Arabia’s first public sukuk issuance.

However, due in part to the financial viability of the high-profile Dolphin Project, Islamic finance has escaped from its consumer- and commodity-oriented market niche in the Kingdom and migrated to the heavy industry sector of oil and gas, petrochemicals, and manufacturing. SABIC’s chief financial officer, Mutlaq Hamad Al-Morished, reiterated SABIC’s intention to promote Islamic financing and its commitment to funding diversification.

He explained that, “The issuance in a sukuk format demonstrates SABIC’s continuing commitment to promote and lead Islamic financing.” Deutsche Bank also contributed to this diversification through a $10 billion murabaha (Shari’ah compliant sale) to finance the Kingdom’s expansion and future investments program. SABIC, in accordance with its stated goal to promote Islamic finance in the energy sector, assumed Islamic debt packages that equaled approximately 23% of its $21 billion debt package.

However, Kayan, a SABIC-affiliated Saudi petrochemical company, broke all records to date on May 30, 2008, when it announced a comprehensive funding package worth $6 billion, based on a $1.67 billion Shari’ah-compliant tranche structured for a multi-sourced greenfield (new project) project financing. The Kayan Islamic financial tranche exceeds the Yansab Petrochemical Company’s $846.8 million Islamic tranche, PetroRabigh’s $600 million, and the $1 billion Dolphin project financing agreement.

Trend towards Islamization

There have been larger Islamic finance dealings outside of project finance, but the specified transactions represent a clear trend towards the Islamization of loans in the sector. A clear preference for the expertise of Western financial firms is shown by the fact that just two of the 20-bank consortium that provided funding were regional, Islamic banks. These were Al Rajhi Banking and Investment Corporation and Bank Al Jazira.

As further evidence of more energy companies taking interest in the diverse funding opportunities available, Saudi oil giant Aramco, which manages one of the world’s largest tanker fleets, accessed Islamic financing for a portion of that fleet. In another pioneering move, in 2006 ABC International structured and co-underwrote the $26 million Al Safeena Ijara sukuk (ownership of equal shares of a rented property) that offered for the Venus reasons for its absence. First and foremost, the most prominent energy Glory VLCC (an outsized crude carrier), which is an Aramco Pacific Star subsidiary.

The Abu-Dhabi National Energy Company, TAQA, has reaffirmed its plans to foster a congenial environment for Islamic finance in the Gulf energy sector. Peter Barker Homek, CEO of TAQA explained that, “TAQA fully supports Islamic project finance because we believe that it is structurally sound borrowing, in addition to being appropriate to our region’s beliefs and traditions.” To further buttress its goals, TAQA launched a $1.13 billion sukuk to fund its enormous acquisition activities, which reached $6 billion in 2007.

These transactions may evidence a flight from the endlessly leveraged financial products that brought about the economic crisis to what is actually a more orthodox set of asset-backed and asset-based products, integral to Islamic finance.

The absence of Islamic finance in the Middle Eastern oil, gas, and petrochemical sector is nonetheless striking, even though there are salient reasons for its absence. First and foremost, the most prominent energy and financial corporations suffer a knowledge gap as to the workings of Islamic financial instruments. This is ironic in light of the fact that one of the reasons Western financial entities gained a sector foothold was through such competitive advantages as political influence and more adroit market information and distribution programs.

However, as evidence of a further shift of the lucrative Islamic finance market away from Western firms, the Central Bank of Bahrain granted a license to the region’s first bank, incorporated as the First Energy Bank — devoted solely to financing large-scale oil and gas infrastructure projects. The development of First Energy bank also heralds the gradual shift away from Western financial institutions funding GCC oil and gas projects, to local banks taking up the slack, particularly in the tight credit market.

Another reason for the glaring absence is the void of legal regulation and standardization in this sector. While Saudi Arabia is an exception due in large measure to its 2006 Capital Markets Law, most GCC countries lack specialized sukuk laws and laws relating to special purpose vehicles used in sukuk structures. Many financial bodies stayed away from such products because of the legal regulatory risks, the fundamental uncertainty being a pioneer, and the costs of being the first mover in such a field.

The on-going economic reform in Saudi Arabia spread awareness that such specialized instruments are ideally suited for a variety of applications in the area of project finance in the energy sector. Further, the lack of a clear regulatory structure, in particular with sukuks created in Western capitols, but nevertheless involving assets in the Gulf, becomes compelling during bankruptcy proceedings, in which the controlling legal jurisdiction becomes contested. Due to the lack of clarity in bankruptcy proceedings, Moody’s takes a somewhat controversial view that such Islamic loans are unsecured.

However, Saudi King Abdullah’s $400 billion energy stimulus plan, designed to pre-empt possible Saudi economic stagnation resulting from the global credit crunch, will almost certainly use Islamic financial instruments. Western energy companies, once shy about unorthodox financing options, now embraced sukuk issuances. Moreover, Dana Gas, which issued a convertible sukuk on Oct. 4, 2007, experienced such a strong market response, as to increase it twice, until it finally reached $1 billion. Further, Swiss Renewable energy company, EnergyMixx, issued a sukuk to fund expansion for its European-based renewable energy plants. The EnergyMixx sukuk is a first, because it funds a renewable energy project sited in continental Europe.

Even American energy firms are incorporating Shari’ah-based financial instruments. The Texas-based, oil group East Cameron Partners, sold a $166 million sukuk in July 2006, which is actually the first Islamic securitization of note in the US. The aforementioned financing agreements demonstrate a clear trend, in which Western companies utilize Islamic debt to gain access to vast GCC oil wealth and GCC Arab firms are turning to Islamic financing to speed up European energy acquisitions.

Nonetheless, many of the more grandiose sukuk offerings have already become victim to the international financial tsunami. Doha Bank sukuk, which initially planned to issue a $1 billion sukuk to finance investment in renewable energy, with a portion to set up a greenhouse gas trading center, is delayed. Doha Bank CEO Raghavan Seetharaman stated that due to the market turmoil, he would hold the sukuk “perhaps until next year.”

The supporters of Islamic finance argue that despite the lack of standardization, excellent reasons exist to support Islamic finance over traditional Western financial instruments. They state that Islamic finance offers greater transparency and accountability and — in the Enron age — may allow greater insight into a company’s financial straits. Islamic finance further places constraints on the debt levels that a company can undertake, and mandates that financing is based on tangible assets, not cash flow.

Advocates for Islamic financing point to the fact that the lender is also a participant and that the creditor has a vested interest in seeing the project succeed during the life of the transaction. This contention should be taken in light of the sub-prime crisis, which was based on the securitization of risky mortgages and debts. The argument is that this type of funding would be virtually impossible to structure under the Islamic model, at least in its current manifestation. Islamic finance also tends to avoid overly speculative loans, which may provide investors with merely theoretical safeguards, as for example, “credit swaps.”

However, despite the efforts of its proponents, the sukuk market has been slowing down. Until quite recently, the sukuk market nearly doubled in size every year from 2004, when it peaked at around $90 billion this year. In illustration of the importance of the sukuk market over the past years, the UK has virtually removed all of the legal and tax obstacles for sukuk issuance. The government even debated the possibility of its first ever sovereign sukuk; however, the market downturn caused a hasty retreat, with the UK treasury stating that a sukuk issuance under current market conditions is currently not “value for money.”

As a further gauge of the financial crisis on the sukuk market, Standard & Poor’s reported that, during the first eight months of 2008, sukuk issuance reached $14 billion, compared to $23 billion over the same period last year.

Actually, reasonable persons may disagree as to whether the sukuk slowdown resulted from the global financial crisis or the observation offered by prominent Islamic cleric, Muhammad Taqi Usmani, who declared in February 2008, that he found the definition of “risk” so mutilated that there is no functional difference between conventional interest (Riba) bearing bonds and sukuk.

There could be cause for even greater alarm, since the board that Mr. Usmani directs, the Bahrain-based Accounting & Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), concluded that as many as 85% of current sukuks may be “unIslamic.” The AAOIFI’s board of scholars issued rules that, essentially reaffirmed, that issuers of sukuks must legally transfer ownership of tangible assets to bondholders, as opposed to basing it on cash flow. Since the impact of that ruling is unclear, the current drop may be a slight correction while the sukuk market regains its bearings. sukuks are still being issued, although it is not yet what one would consider a “liquid” market, such as development of a secondary market.

It is clear that despite the credit turmoil, energy firms, from the private sector to the national energy firms, are diversifying their funding options. Islamic finance in the Gulf’s lucrative energy sector will proceed apace, and an increasing amount of business will go to indigenous banks. Much as Dolphin legitimized Islamic financing for Gulf energy projects, a large offering by a highly-regarded GCC government (Saudi Arabia is the preferred country) would add credibility to the market and serve as a benchmark for future investment potential.

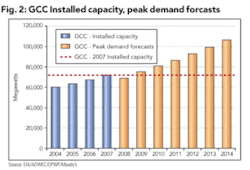

GCC governments want to get involved, from concern that the meteoric growth of the sukuk usage may lead to lapses in Shari’ah compliance and corporate governance, especially in a region which is as under-regulated as the Gulf finance sector. The GCC nations have need furthermore of a multibillion-dollar power sector overhaul. The Gulf countries are going to need to secure billions of dollars in energy investment over the next few years in order to meet their gargantuan energy needs (Fig. 2).

Power shortages have already been experienced in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, with more expected to come. The crux of the power problem is twofold: the demographic increase which put a strain on local utilities and the below-market pricing for gas destined to the domestic market. These two factors combined have put the majority of the Gulf countries in an unenviable position.

According to a Moody’s Investment Services report on the Arabian Gulf electricity industry published on Oct. 7, 2008, the GCC will need as much as $50 billion by 2015 to boost total power generating capacity by 60 gigawatts in order to keep pace with demand growth. Further extensive investments will also be required to modernize and expand power transmission and distribution networks.

With a virtual credit freeze in the West, it is likely that the GCC governments will turn to the regional Islamic finance market to develop the sector. But as the sophistication of Islamic financial products increases, investors from Islamic nations will increasingly migrate to Islamic finance, and eschew the conventional financial instruments for development of their megabillion-dollar energy projects.

At the same time it must be noted, Islamic financial instruments are not a jealous suitor. As many energy companies have demonstrated, traditional finance is always available for diversification purposes.

About the author

Justin Dargin is a research fellow at the Dubai Initiative — Harvard University, where he researches energy policy in the Persian Gulf region. He specializes in carbon trading, oil and gas production in the Gulf, and the legal framework surrounding the Gulf energy sector. During his graduate legal studies, he interned in the legal department at OPEC. Dargin was also a research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies and is working on his second book related to the energy sector. He is fluent in Spanish, English, and Arabic.

London becomes Islamic banking hubIslamic banking is growing in popularity — not only in Muslim nations but in Europe as well, particularly in the United Kingdom. London, which has become a hub of Islamic banking outside the Middle East, is now home to 25 companies offering some form of Islamic financing, according to US News and World Report.

The largest of these institutions is the Bank of London and the Middle East, or BLME, which strictly follows sharia law rather than conventional Western banking practices. sharia-compliant banking calls for alternative structuring of loans and financing since the centuries-old religious laws forbid bank interest and trading and debt.

Kuwaiti-owned BLME is the largest of five wholly sharia-compliant banks operating in Britain. The first, the Islamic Bank of Britain, opened in 2004, and the number is expected to double within five years. Some conventional banks are even offering sharia-compliant products.

One issue is a lack of standardization. Religious scholars are typically put on the boards of directors of the banks, and definitions of what are acceptable banking practices can vary from region to region and from bank to bank. Malaysian banks tend to offer more flexible interpretations of sharia-compliant products than do their conservative counterparts in the Gulf, so there is often a lack of uniformity in banking practices.

The UK has become a focal point of Islamic banking in the West because of its historic links to the Middle East and because of its strong financial talent pool. The London Stock Exchange began listing sukuks, a type of Islamic bond backed by ownership of a tangible asset that produces a financial return, this year, and 18 are now trading on the exchange.

Globally, the Islamic banking sector total assets are estimated at between $500 billion and $1 trillion and growth is between 10% and 15% annually.

Islamic banks have avoided the sub-prime fiasco, according to an executive with BLME, who adds that there are no problems with big write-offs, as is the case with most Western banks, and there is still ample liquidity.