If carbon legislation passes, what will the future hold for US petroleum industry?

Aileen M. Hooks,Baker Botts LLP, Austin

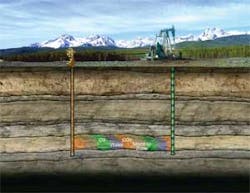

For many years, carbon dioxide (CO2) has been injected into oil and gas formations to extract oil and gas that remains after primary recovery operations, a process known as enhanced oil recovery or EOR. While some amount of the CO2 injected for EOR may remain permanently trapped in the underground formation, this is an incidental result.

By contrast, the current focus on carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a climate change mitigation tool would involve the injection of large quantities of anthropogenic CO2 into appropriate underground geologic formations, including depleted oil and gas reservoirs, for the purpose of long-term storage. The purpose of this carbon sequestration would be to mitigate climate change by preventing the CO2 from being released into the atmosphere.

Repurposing depleted oil and gas reservoirs

CO2 associated with the use of fossil fuel is a primary target for curbing the growth of the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases widely believed to be responsible for climate change. In the long term, it may be possible to reduce the world's reliance on fossil fuels through increased development and deployment of renewable and low carbon sources of energy and thereby to reduce CO2 emissions.

Reduced reliance on fossil fuels as an energy source has been estimated to be at least 50 years away. As a result, in the nearer term, there is a great deal of focus on technological solutions that would avoid CO2 emissions from major emitters, most notably coal-fired power plants, and secure the CO2 that is generated and that would have been emitted through injection and permanent underground storage, or sequestration. This is commonly referred to as carbon capture and storage or carbon capture and sequestration.

CCS involves separating the CO2 component of exhaust gases from an emitting facility, compressing the CO2 so that it can be transported by pipeline to an injection site, and injecting the CO2 into suitable underground formations for storage. The voids or pore space created following oil and gas extraction make depleted oil and gas reservoirs good candidates for carbon sequestration.

CCS is widely viewed as an integral component of an effective climate change mitigation portfolio for the 21st Century. In its 2005 Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that CCS has the potential to contribute between 15% and 55% of cumulative global climate change mitigation effort this century.

Currently, only four commercial scale CCS projects, located in Algeria, Canada (Alberta), Norway and the Norwegian Sea, are in operation worldwide. The annual injection rates for these projects range from 0 .7 to 1.2MtCO2. To realize the potential suggested by the IPCC, several hundreds to several thousands of CCS systems, each capturing 1-5 MtCO2 annually may need to be installed. Sequestered CO2 will need to be stored and not reenter the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years for CCS to be an effective climate change mitigation tool.

In the United States, considerable effort and funding, including stimulus funding, is being applied to the development of CCS technology and CCS demonstration projects. The states having the greatest potential capacity for CO2 storage potential in oil and gas reservoirs in are Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and California, in that order, with Texas having an estimated capacity in the range of 47 billion metric tons, nearly eight times the projected capacity as New Mexico, the state with the second largest estimated oil and gas reservoir capacity. The offshore US oil and gas reservoir CO2 storage capacity is estimated to be about twice that of New Mexico.

CCS legislative framework lacking

To provide the complete concrete and predictable legal framework needed to support CCS project development at a commercial scale in the Unites States, numerous legal and regulatory uncertainties concerning the laws and rules that will apply to CCS, including geologic carbon sequestration, must be resolved. The manner in which these issues are resolved can have a significant impact on current and future oil and gas exploration and production activities.

Various state and federal initiatives are underway. In addition to development of the regulatory framework that will govern siting, permitting, operation, and closure of geologic carbon sequestration facilities, the critical pieces of the CCS legal framework that need to come into focus to foster commercial scale deployment of CCS in the United States relate to property rights and liability issues. This article focuses on storage/sequestration aspects of CCS. However, in addition to rules governing the injection and storage of CO2 in the geologic storage facility, there must be rules governing the capture of the CO2 and the siting and operation of the CO2 pipeline system that will be needed to transport the captured CO2 from the generator's plant to the injection site. It has been projected that the magnitude of the CO2 pipeline infrastructure will match that of the natural gas pipeline system.

Some progress establishing the contours of the legal framework for carbon sequestration has been made, but many unanswered questions remain. A number of states, including Montana, Texas, and Wyoming, have adopted or proposed legislation intended to develop the legal rules for CCS. In Texas, for example, two bills designed to promote carbon sequestration were passed in the 2009 legislative session. One bill, S.B. 1387, which addresses carbon sequestration in oil and gas reservoirs and overlying and underlying saline formations, is focused on on-shore carbon storage facilities and the relationship of such formations to enhanced oil recovery. The second bill, H.B. 1796, promotes the establishment of an offshore carbon dioxide storage repository on state lands.

In July 2009, US Senators Mike Enzi (R-Wyo.) and Robert P. Casey (D-Pa.) introduced the Carbon Storage Stewardship Trust Fund Act of 2009 in the US Senate. The legislation would address long-term liability issues by having the Department of Energy serve as the long-term steward for CCS storage sites that have been issued certificates of closure.

The US EPA has proposed regulations under the Safe Drinking Water Act for permitting of underground injection control wells for carbon injection. However, none of these initiatives provides a comprehensive solution that addresses the full array of the liability and property rights concerns associated with geologic carbon sequestration nor do they adequately consider consequences to the oil and gas industry. Of particular note, the measures to date fall short in harmonizing mineral exploration and production activities with permanent carbon storage activities in oil and gas reservoirs.

Whose space is it, anyway?

Among the most vexing legal issues associated with carbon sequestration are those related to real property laws. From the threshold questions of what property rights are needed to inject carbon into subsurface formations and who has those rights to the process for and cost of securing and protecting the necessary rights, the property issues and associated financial implication relating to CCS are complicated and largely unsettled. These questions have a number of facets, including:

- Who owns the geologic formation (depleted oil and gas fields, saline aquifers, coal seams) into which the carbon will be injected for storage?

- How will oil and gas reservoirs transition to permanent carbon storage formations? When will an oil and gas reservoir be considered "depleted" and ready for carbon storage? Will there be any consequences for injected produced waters?

- Who owns the injected CO2?

- What costs will be associated with acquiring pore space rights and what other compensation and indemnity rights and obligations will be created?

- How will a CCS project developer be able to secure needed property rights from recalcitrant property rights owners? Beyond contractual agreements what mechanisms will be available to acquire pore space rights?

- What property rights holders will be required to be given notice of and/or consent to a proposed carbon storage facility?

- What surface interests will a CCS operator be required to secure?

- What role, if any, will potentially impacted water users have?

- How will competing rights and interests of mineral interest holders and those holding the right to sequester carbon in mineral formations be reconciled?

- What restrictions will be imposed on activities that could negatively impact mineral interests?

- What restrictions will be imposed on future surface/subsurface uses and activities that could impact sequestered carbon?

At this point, it is safe to say that there are far more questions than answers concerning the property rights aspects of geologic carbon sequestration. For sequestration that occurs under state and federal lands, the property rights issues presumably will be far more straightforward.

It has been said that a landowner interest in his property extends from the surface to "the center of the Earth," which would be over 3,900 miles. Whether the "center of the Earth" theory is binding law or hyperbole remains to be seen. There have been increasing suggestions that much like the US Supreme Court put a bound on a property owner's airspace rights "up to the heavens" to make way for aviation, there should be a bound to the depth of subsurface ownership rights based on reasonable expectations to make way for carbon sequestration. However, treating deep underground pore space as a public resource rather than a private property interest is likely to draw opposition and claims of regulatory taking. While the approach may have some appeal from the standpoint of promoting carbon sequestration as a matter of public policy, one potential problem with this approach is the well-established body of law concerning subsurface mineral interest rights, which are found at the same depths that would be used for carbon storage.

It might be possible to make a distinction between formations with extractable minerals and those that will be used for carbon storage. While expected to draw criticism, treating deep underground formations as a public resource akin to air space would entail a reconciliation of technological developments and the public interest with reasonable expectation concerning scope of private property ownership, including the expectations and rights of mineral interest holders.

Subsurface property ownership rights are generally a matter of state law. The states that have passed geologic carbon sequestration legislation and addressed the property rights issues have provided that, absent an express written agreement to the contrary, the surface owner is the owner of pore space in the candidate formations for carbon sequestration. Wyoming Bill No. 89, passed in early 2009, is one of the few if not the only current legislation that expressly addresses geologic sequestration property rights issues beyond imposing a property owner consent requirement. The statute provides that "[t]he ownership of all pore space in all strata below the surface lands and waters of this state is declared to be vested in the several owners of the surface above the strata."

While seemingly settling the pore space ownership question, the Wyoming law creates a framework that would require consent of multiple real property interest holders with open issues on how and whether the consent requirement would be satisfied for large scale projects. While there appears to be a prevailing view that, absent express documentation to the contract, the surface owner owns the pore space, this is not a foregone conclusion. There are arguments that the mineral interest owner either on its own or together with the surface owner own the pore space as well as arguments in favor of the treatment of the space as a public resource.

Beyond the question of pore space ownership, the size of the carbon "plume" on a commercial scale project calls into question the application of traditional property right concepts to geologic sequestration, which would suggest that the CCS operator would need to secure comprehensive property rights. Potentially affected property interest holders include surface owners, mineral rights interests, and water users. Considerations include the time, expense, and uncertainty associated with consent process; condemnation rights and compensation, taking into account impact on mineral interest holder rights; and the potential to use a unitization approach as Wyoming legislation does to facilitate property rights acquisition. If consents will be required, it is expected that the resolution of liability issue of property interest holders will affect willingness of the interest holders to provide consent.

CCS Reg Project, which is a collaborative policy development effort funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and led by Carnegie Mellon University's Engineering and Public Policy Department, calls for adaptive management of project risks and a dynamic approach to the development of the regulatory infrastructure so that the lessons of the pilot projects and the projects that initially deploy CCS at the commercial scale can be used to inform the ultimate regulatory framework.

While it would be ideal to take the two-step approach CCS Reg Project promotes, there is also an inherent and real risk that the legislative and rulemaking processes will be too slow to respond in time for wide-spread commercial deployment to effectively implement CCS in the needed time frame. The legal uncertainties engender financial uncertainties. Prolonged uncertainty concerning the details of the regulatory framework and the associated compliance costs and liability risks could have a chilling effect on investment in expensive CCS projects.

Moreover, in order to avoid an inconsistent state-by-state patchwork of laws, the time has come for legislative and regulatory action that will provide much-needed certainty to foster commercial scale deployment of CCS in the United States.

About the author

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles