The perplexing paralysis of private equity

Cameron O. Smith,The Rodman Energy Group, New York

A survey of the Rodman Private Capital Energy Index reveals that, through the first half of 2009, private capital invested a mere $2.9 billion, relative to the $7.6 billion for the second half of 2008 and an average of $6.6 billion per each six-month period during 2008 and 2007. Furthermore, only $600 million of this $2.9 billion in the first half of 2009, in fact, was invested in new portfolio companies or projects, with the remainder going in support of existing commitments.

What's going on, here? The author sets out in the following article his take on the state of energy-focused private capital at mid-year 2009 and expands in an addendum some of the reactions a draft of this article elicited, when circulated to several of energy's leading private equity funds in mid-September.

History

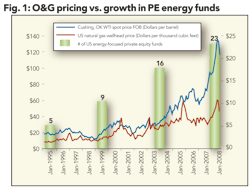

The last time there was a downturn in prices comparable to the fall of 2008 was the winter of 1997, when oil prices dropped from the mid $20s to $12 and below, with a similar decline in gas prices. Not until 2000 did these prices recover materially, but thereafter, for both commodities, they rose steadily until they crested during the first half of 2008 (see accompanying graph). This means that any energy investments made by private capital in funds formed from roughly 1998 until 2005 or 2006 saw nothing but rising commodity markets and extremely favorable exit circumstances.

As it happens, this period also witnessed a proliferation of private capital funds and managers focused exclusively on energy, with only First Reserve, EnCap, Natural Gas Partners, HM Capital, and Yorktown established prior to 1997. This means that the founders of the 20-plus energy-focused private capital fund managers that have been created since then, let alone their lieutenants and associates, have never as a principal investor in their current funds witnessed a downturn before these past 12 months.

Furthermore, as the steady rise of petroleum prices through the first decade of this century and the increasingly robust public energy markets made exits all the more lucrative, and energy-focused private capital managers returned ever greater profits to their investors, the latter placed ever greater pressure on the managers, themselves, to create new and ever larger funds to facilitate their continued investment in the sector.

The result, as indicated in the PEIR Survey over the past several years, was that the total aggregate capital committed to these funds burgeoned during 2006 and 2007, and, then, particularly in the first half of 2008. This forced or induced fund managers to add more and more staff to handle the greater volume of commitments, just as the costs associated with the industry spiraled out of control and the commodity price cycle cracked and then collapsed.

To complete the picture, the preferred business plan of this period emphasized capture and testing of unconventional reservoirs, which, with expenditure of minimal capital, could imply the presence of vast resources, which others in the public market, driven to show huge inventories of drill sites, could hardly resist.

The problem with this plan in a falling commodity market is that, below a certain price, all these drill sites become uneconomical, exits disappear, and management is left with the challenges of actually operating their properties, drilling efficiently, forcing down costs, and establishing production.

This, unfortunately, has revealed three other further, potentially fatal deficiencies: 1) the very talents that comprised attractive management teams under the first scenario—geologists to identify the right rocks and landmen to capture the related geography—are not those required by the new circumstances, which now emphasize operational engineers and accountants; 2) the teams assembled by fund managers during the past decade were selected to review investments, not to manage them; and 3) particularly with respect to those investments made three or more years ago (2005/6), fund managers were timing their investment to exhaust the capital by 2008, when they had targeted exit. They were consciously reserving little or no "dry powder" in order to create an efficient liquidation for the benefit of that fund's investors.

The result, however, has been to leave the related portfolio company high and dry, with no new equity on which to draw. As a consequence of these factors, as the business plans of the past half-decade entered the commercial rip-tides of the past 12 months, both sets of managements—portfolio companies' and fund managers'—were blind-sided, their lifeboats tipped over, and their oars and provisions swept away.

"EnCap invested more than $900MM in 2009, most of it in existing portfolio companies."– Doug Swanson, EnCap Investments

A script run dry

No wonder, then, that, at least as to investment in new portfolio companies, private capital has been paralyzed over the past 12 months. Fund managers, not used to it, are being forced to perform triage on the companies in their portfolios, trying to ascertain which of their managers can navigate the surf, which require and deserve a lifeline, and which, cruelly, but necessarily, must be jettisoned overboard.

The problem with this is that these snafus within the portfolios are monopolizing the attention of each fund's most senior and experienced managers. A great, though extreme, example of this is the appointment in March 2009 of Alan Smith, a managing director of Quantum Energy Partners, as president and CEO of Quantum Resource Management, effectively placing him in charge of the operational management of one of Quantum's portfolio companies and removing him from his line responsibilities at the fund, itself.

These, in fact, are the more subtle damage and insidious danger that face private capital in the current crisis: Without their most experienced managers available to review new investment opportunities, many funds are delegating this function to the new generation of managers who not only have never seen a downturn, but act as if they have been handed a script dictating what to look for, and, if any detail strays, however fractionally, off-course, the best solution is to send the candidate sailing.

So, what is the current script for new teams seeking financial backing? Private capital is currently looking to place growth capital with going-concerns, which, themselves, have a complete, operationally savvy, fully invested management and a boat-load of PDP reserves, and whose intended course is set to capture additional such reserves from financially strapped sellers with whom management has relationships sufficiently close to ensure a negotiated (non-competitive) purchase. Unfortunately, this script also calls for the fund to apply these same expectations to the value of the assets and securities it expects to purchase from these prospective portfolio candidates, thus relegating them to the same class of fictitious distressed seller scripted for future transactions.

If the prospective portfolio company managers are, indeed, savvy, they will have seen the values that the public market, not to mention the property market, itself, is already once again assigning reserves and find this attitude somewhere between insulting and ludicrous. They will know anecdotally, even if not equipped with hard data from the Rodman Energy Index Survey, that there is currently more capital committed to private capital, seeking to acquire reserves, than at any time in the past 10 years, let alone the funds allocated by the public and retail markets and industry, itself.

Savvy managements are not targeting acquisition of PDP reserves; they never do. They are figuring out ways to capture them through drilling or other technological means that, with far greater certainty than competing in auctions, deliver low finding and development costs. Savvy operators know better than to stay on script. And savvy entrepreneurs know their own self-worth far too well to deliver themselves to bondage at fire-sale prices.

Conclusion

So, what could be the result? Unless the managers of the private capital funds wake up soon and pay attention to new business, the risk is that they and their current investors will miss out on this generation of true value creators, the managements that are best equipped, both with imagination and experience, to take advantage of the current crisis.

The irony is that those funds best situated to flourish during this transition are those that 1) have been away from energy for the recent few years, like Morgan Stanley's Private Equity Fund, 2) are relatively new, like Pine Brook Road Capital, or, 3) like EnCap Investments, monetized an extraordinary number of their portfolio companies prior to mid 2008.

Whatever the circumstances, history tells us that the absolute best-performing funds are those that invest during periods of low prices and distress. Experience also teaches us that the best investment always is in people. If it takes paying up to become associated with the best and to have them serve as your pilots through the roiled waters of uncertain times, what better investment can you make? The alternative is to stay in harbor, miss the tide, and rot away at anchor.

Private equity's response (in alphabetical order)

Asked to comment on the topic of this article, here is what several leading private capital providers had to say:

EnCap Investments LP: Doug Swanson wrote, "Well thought out and fairly accurate." Regarding the EnCap realizations in 2008, Marty Phillips commented, "To be fair, we didn't see the downturn in prices, but we saw opportunities to monetize and took chips off the table when available." Swanson added that EnCap had managed to invest over $900MM in 2009, although he admitted it was primarily in existing portfolio companies.

Kayne Anderson Energy Funds: Danny Weingeist took little issue with the article's analysis, instead pointing out that in 2007 and 2008, Kayne simply saw "very little opportunity in which to invest." He stated that, while Kayne probably reviewed some 50 opportunities a year during this period, it only closed on 5 to 10 per year, showing how oversold the industry was. Weingeist went on to say that through August, Kayne had closed six deals in 2009 – "about the same run-rate as in years past, but with far fewer reviewed, suggesting better quality opportunities currently available." Most of Kayne's deals, he added, were and are conventional – not resource plays, and this year he's emphasizing conventional oil acquisitions and "shaley" gas joint ventures.

Lime Rock Partners LLC: Jonathan Farber wrote simply that he ascribed the "lack of PE activity over the last nine months…to the fact that overall North American activity is down approximately 90% year/year." This point was echoed by J McLane in a far longer response, ascribing private equity's inactivity to "enormous bid/ask spreads in private market transactions over the past 18 months." He pointed out that valuations in the public markets over this period have been far more favorable and that Lime Rock had, in fact, made several investments in public field service businesses so far in 2009. J also suggested a better measure of private equity's contributions to financial activity would be to review the ratio or change in PE activity relative to overall M&A activity. "I'm not sure of the answer," he admitted, "but my guess is that PE [has been] slightly more active, especially since a lot of capital continues to go into good, but existing teams to capitalize on the downturn, rather than new relationships."

Natural Gas Partners: Billy Quinn was more than gracious: "Overall, not bad," he extolled. To elaborate, "I think you completely miss a few critical points... For starters, some of the lack of activity has to do with the property market. What was once a $75 billion North American market is on a $7 billion to $8 billion run rate." He went on to point out that both LPs and GPs now want to see a much slower rate of investment—"spread over 3 or 4 years, not 1 or 2." He also thought the article's comments about the founders being less active were certainly unfair to NGP and he assured me that all the senior partners at NGP are "busting their butts" looking at new deals, but "we're not going to act for the sake of activity" (I assume no matter what I write!).

SBE Partners: John Cleveland wrote: "Good article. I think you tell the story pretty well, here." He did want to make a couple points: "Many of the managers that started new funds came out of other parts of the energy industry, many from the finance side, who did in fact experience the cycles of the 1980s and 1990s." "Not everyone was a newbie," he asserted. His other point was that many management teams, in fact, do have operating expertise and are "up to the challenge of drilling, completing, and operating wells." Those, he acknowledged, are likely to be survivors; those that don't, he acknowledged, are challenged in this environment.

Quantum Energy Partners: Wil VanLoh didn't hold back: "I think you have significantly mischaracterized Quantum in your paper," he wrote. It turns out that he was upset about my characterization of Alan Smith's departure from QEP to head up Quantum Resources. Alan, he asserted, had always been slated to go back as a principal to head a new portfolio company, but when QR had its "bobble," it was a great opportunity for Alan. Wil then quoted figures to suggest, in fact, that QR is in fine fiscal shape. He went on to say that, while it was true that Quantum had been very quiet the past 18 months, it was because he felt the "script was unwritten, not run dry!" Much of the past year, Quantum, in fact, had been "studying and thinking and plotting." He then said that was over, and he expected to be "very active" over the next year. Investments, he thought, were likely to be larger: 6 to 7 per fund, rather than the previous 15 to 18, because to be successful, companies had to achieve greater scale and probably exit through the public option. He's cool to unconventional plays: "90%," he claimed, "are uneconomical." But he is high on midstream and gas storage and certain renewables, as well as conventional E&P.

Wil VanLoh is "cool" to unconventional plays and says 90% are uneconomical. But he is high on midstream and gas storage and certain renewables, as well as conventional E&P.

Yorktown Energy: Peter Leidel was kind: "Good article. I agree with most of what you have said." He then went on to assert that, despite the fact that "there aren't many high quality assets available at attractive prices," Yorktown 8, which was closed in September 2008 with over $1 billion, is experiencing "the fastest investment pace we have ever had." He also pointed out that Yorktown over the past year had made a "big effort to distribute more than it called down in new capital," which obviously has been appreciated by its investors, "many of which have their own liquidity issues."

General comments

Many of the respondents took specific issue with the inferences they drew from the article regarding the good stewardship or fortune of certain of their peers, while, of course defending their own performances. Chalk it up to "EnCap Envy."

As to the other overarching theme—that the lack of a transaction market is the fundamental reason that PE has in the main remained on the sidelines—speaks volumes regarding the current bias of PE against drill-bit driven business plans. Virtually none of the respondents mentioned lower drilling and completion costs or the extraordinary opportunities to farm-in or drill to earn low risk PUD or non-proved reserves, for example.

Overall, however, this was a fascinating exercise and confirms that private equity and its managers are nothing if not nimble in dealing with adversity and assiduous in pursuit of opportunity.

About the author

Cameron O. Smith is senior managing director of Rodman & Renshaw and head of The Rodman Energy Group.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com