Global shale lagging - here's why

Gas-to-wire modular development model proposed for shale infrastructure in some countries

André Olinto do Valle Silva, Matheus Nogueira, and André Ramos, SBC, Rio de Janeiro

Shale gas development has revolutionized the US energy industry, reversing a trend of rapidly declining domestic production. Between 2000 and 2015, natural gas production from shale rocks increased by 10 Tcf/year, while non-shale production fell by 4 tcf/year - a slump of almost a quarter.

The perennial question is whether the US shale revolution will be replicated elsewhere around the world. The potential is certainly there. The US Energy Information Administration, for example, estimates that more than 90% of the world's technically recoverable resources are outside the US. But this potential has not yet translated into significant production, even 10 years after the start of the US shale-gas boom (Figure 1).

Infrastructure barrier to shale development cycle

One reason for the slow progress is the limited reach of gas pipeline systems in many of the countries that have promising geological potential. Over one-third of prospective shale gas fields in the 10 largest shale gas countries outside the US have no access to gas pipelines. Overall, the gas pipeline density in these 10 countries is 30 times lower than in the US.

The shortage of infrastructure is a barrier to E&P activity in general, both in conventional and unconventional developments. But it is particularly problematic in shale gas projects. Because of the heterogeneous nature of shale formations, reserves must be proved on a well-by-well basis, which requires intense drilling activity and a large number of wells. Indeed, on average, shale deposits require 10 times more wells than conventional deposits in order to prove same amount of reserves (Figure 2).

In conventional E&P, reserves are mostly proved during the exploration phase, after which a final investment decision is made (Figure 3). In shale gas operations, by contrast, resource-evaluation is a continuous, cyclical process (Figure 4). New wells are drilled with two purposes: monetizing production and generating cash flow; and acquiring subsurface data in order to provide a continual assessment of resources in place. The prospect of profitable reserves additions encourages the drilling of new wells and increases the cycle's momentum.

In the US, extensive infrastructure has enabled the immediate monetization of successful wells, encouraging gas companies to drill and strengthening the shale development cycle. Thousands of wells have been drilled every year in several US shale plays, enabling operators continuously to prove up reserves. But this cycle is unlikely to be sustainable in areas with no access to gas pipelines: if there is no immediate means of monetizing production, large drilling campaigns, involving thousands of wells, are unlikely. As a result, no significant amount of reserves will be proved and pipeline investments will remain too risky (Figure 4).

Opportunity for gas-to-wire modular development

In several of the 10 largest shale gas countries outside the US, electricity transmission networks are considerably more extensive and dense than gas pipeline systems. The electricity networks of China and South Africa, for example, are 10 times denser than their respective gas networks.

Examples of prospective shale-gas basins that lack pipeline access but that are served by transmission lines include Paraná in Brazil, Karoo in South Africa, and Songliao in China. Some of these resources are more than 500 kilometers (about 310 miles) away from the nearest gas pipeline.

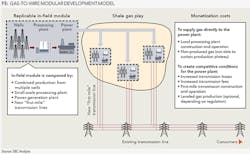

Relatively extensive electricity infrastructure creates opportunities for an alternative, gas-to-wire (GTW) monetization model. This alternative model, which is being proposed in this article, is designed to develop shale-gas reserves in relatively small modules that can be systematically replicated within the field, consisting of a group of wells capable of producing at an expected plateau, connected to in-field gas processing and power generation plants, to generate electricity and send it to consumers through existing transmission lines (Figure 5).

The plant's capacity determines the size of modular reserve required - i.e. the amount of gas needed to supply the power plant over its operating life. As such, this alternative monetization model enables sustainable economic production in regions with no gas infrastructure when only a relatively small amount of gas reserves is proved, which requires a limited number of wells before final investment decision: a 100 MW combustion turbine (CT) would require, over its 20-year operating life, modular reserves of 0.15 tcf, which can be proven by an estimated 30 wells; a 500 MW natural gas combined-cycle (NGCC) power plant, meanwhile, would need 0.6 tcf, or an estimated 120 wells in order to prove reserves.

Several incremental costs, or monetization costs, would need to be factored into the local gas-sale price in order to make the gas-to-wire model successful. These costs falls into two groups: (1) the incremental costs of supplying gas directly to a power plant; and (2) the incremental costs of creating competitive operating conditions for the power plant.

The first group comprises: the costs of constructing and operating an in-field gas-processing plant; and the cost of non-produced gas (the portion of the reserves that will not be able to sustain the expected production plateau, due to combined well declines).

The second group comprises: costs related to increased transmission losses; higher transmission fees; the construction and operation of first-mile transmission (i.e. connection between the in-field power plant and the nearest transmission line); and the incremental cost of producing gas with little variability from the expected production plateau, which will be necessary in case regulation or commercial terms impose the need for a constant supply of electricity.

Attractive economics

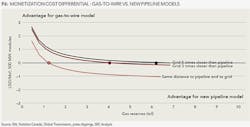

Since electricity-transmission networks in the 10 largest shale gas countries outside the US are up to 10 times denser than gas-pipeline systems, distances from prospective areas to the grid are likely to be shorter than distances to the nearest available gas pipeline. The ratio between these distances is a fundamental factor in determining the relative economic attractiveness of modular gas-to-wire model and the pipeline-transportation model.

The proposed model tends to be the better alternative the greater the ratio becomes or the smaller the gas reserves being considered for development. When the distance to the grid is the same as the distance to a gas pipeline - a ratio of 1:1 - gas-to-wire is an attractive alternative for plays with reserves of up to 1 tcf. This rule-of-thumb (ratio of 1:1) is often used to model the economics of gas-to-wire systems but, in some regions, the 1 tcf figure is too conservative and caps the attractiveness of GTW model at too low a level (Figure 6).

However, the cap on the size of reserves increases in relation to the relative proximity of available transmission lines. For example, the proposed model remains attractive for reserves as large as 3 tcf or 6 tcf if the distance to the grid is three or five times shorter than the distance to pipelines, respectively.

The modular gas-to-wire model is expected to be a competitive economic solution for monetizing a shale play 500 km from gas pipeline infrastructure but five times closer to the grid - i.e. 100 km. With modular sizes of 500 MW or 100 MW, this model can add $1.4 to $1.5 per Mcf respectively, as costs of monetizing the gas, respectively. This cost is comparable to the estimated $1.2 per Mcf cost of monetizing gas produced in an area with access to gas pipeline infrastructure and 500 km distant from the gas delivery point.

In case of non-existing gas infrastructure, constructing a new pipeline to monetize gas to a delivery point situated 500 km away from producing area would only be an attractive option if the reserves exceeded 6 tcf. But proving up this amount of gas would require the drilling of more than 1,200 wells. However, constructing a pipeline before proved reserves reached 6 tcf could result in extremely high monetization costs if exploration fell short of expectations. For example, if 0.5 tcf or 1 tcf of gas were discovered for a pipeline that had been built to monetize over 6 tcf of gas, monetization costs would reach $4.8 or $3 per Mcf, respectively.

The biggest sources of monetization costs of the proposed gas-to-wire 500 MW modular development model are: $0.6 per Mcf for constructing and operating an in-field gas processing plant; $0.3 per Mcf for constructing and operating the first-mile transmission line; and $0.3 per Mcf for increased transmission fees, assuming distance-sensitive tariff for transmission. However, the distance-sensitive tariff method is a conservative assumption in view of other tariff structures (e.g.: the classic postage stamp electricity tariff model).

Depending on the regulatory framework of local power generation markets and commercial terms with consumers, power output might need to remain flat, with no variability throughout the plant's operating life. This would require a similar gas-production profile. Additionally, power-plant operations can be adversely impacted by variations in gas-supply volumes, which could also force the operator to adopt production-variability reduction measures.

In order to minimize this problem and ensure gas supply stability, a production buffer can be created by anticipating drilling campaigns. In such a situation, production could be controlled by choking back wells during periods of surplus.

Measures such as this can ensure virtually stable production - a 95% chance of achieving gas production variability of less than 1%. This would increase the cost of gas at the wellhead by a factor of ~10%. For example, monetization costs would increase by $0.3 per Mcf if producing costs were $ 3.00 per Mcf. If variability-reduction measures were not adopted, probabilistic Monte Carlo simulations indicate, with a confidence of 95%, that gas output would typically vary ± 20% from the expected production plateau. Cost and variability parameters would vary according to several factors, such as the initial production rate from wells and plateau production volume.

Promising alternative

The gas-to-wire modular development model is a promising alternative for shale plays in underexplored basins with no access to gas pipeline infrastructure, but with reasonable access to electricity transmission networks. In order for plays fitting this description to be commercial, the cost of gas at the wellhead must be lower than the traded price at the city gate, discounting the cost of monetization.

The model's attractiveness is further strengthened when the required investments are taken into consideration. This is because the proposed model drastically limits the number of wells required to prove up the reserves needed to justify capital expenditure on monetization infrastructure (either pipelines or GTW-related investments).

About the authors

André Olinto do Valle Silva is senior vice president and Brazil office manager at the SBC office in Rio de Janeiro, having led that office since 2009. Prior to that, he was a senior partner at McKinsey & Company, where he led the electric power and natural gas practice in Latin America and served clients in the energy and basic materials sectors for more than 14 years. Olinto has an electrical engineering degree from Pontificia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, where he also undertook graduate-level studies in statistics and operations research. He has an MBA summa cum laude from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business with a concentration in finance and accounting.

Matheus Nogueira is a vice president with SBC, based in Rio de Janeiro. He is an experienced oil and gas professional, having worked both as a strategic management consultant and in several managerial roles within Schlumberger. He has broad international experience, having worked in North and South America, Europe, and Africa for a wide range of clients in exploration and field development projects the last 15 years. Nogueira has a degree in mechanical engineering and has developed a patented solution in fluid sampling, which has been adopted by the industry worldwide.

André Ramos is a consultant with SBC, based in Rio de Janeiro. He is a mechanical engineer with a degree from the Instituto Militar de Engenharia. Prior to joining SBC, Ramos was with Shell, where he conducted demand forecast and pricing analysis on fuels and lubricants, both for the maritime segment.