China, Japan clash over East China Sea

ASIA'S LARGEST ENERGY CONSUMERS IN DISPUTE OVER HYDROCARBON RESERVES

MUHAMMAD WAQAS, MECHANICAL ENGINEER, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

CHINA AND JAPAN have had a long-standing dispute over territorial boundaries in the East China Sea, which separates China and southern Japan. The disagreement is mainly over hydrocarbon reserves in the sea and has been exacerbated by the energy crunch both countries are facing.

This article is intended to shed some light on the intractable position each disputant has adopted, which has become an obstacle to resolving the issue peacefully and amicably. It will further examine the ramifications of UNCLOS on this dispute. And, finally, we will discuss the benefits both nations can reap by exploiting the oil and gas reserves jointly in the disputed areas.

CHINA'S OIL AND GAS NEEDS

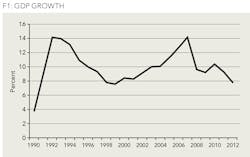

China, the most populous country in the world, is also one of the biggest consumers of energy in the world. As food is to humans, energy is to a country's economy, and this is true for China. China's massive energy costs are driven by a dynamic and vibrant economy that averaged double-digit growth during the first decade of this century (See Figure 1). Although growth has slowed in recent years, the Chinese people have remained upbeat. Such growth would not have been possible without the availability of energy to fuel China's economic engines.

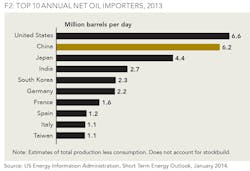

The extent of China's energy consumption during this period of rapid economic growth can be understood from the fact that it was the second largest net consumer of oil. It imported an average of 6.2 million barrels of oil per day in 2013 (Figure 2). A year later, in 2014, it eclipsed the United States as the top importer of oil. However, this is partly due to the emergence of shale oil in America and the recovery of much of the world from a recession.

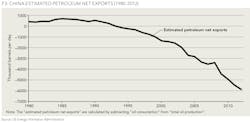

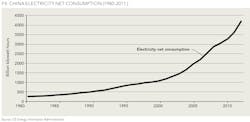

At one time, China was a net exporter of petroleum products (See Figure 3), but its rapid economic growth propelled by the extravagant consumption of energy has turned China into a net importer of hydrocarbons. In just three decades, China's total energy consumption increased five times the level it was in 1980 (See Figure 4).

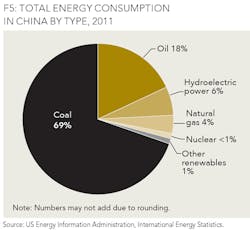

The energy make-up of China is dominated by coal consumption. China is currently producing about 69% of its energy requirements from its vast coal reserves. However, by exploiting its coal reserves, China has largely escaped the lengthy oil and gas bill but that has come at the expense of carbon emissions, which has contributed significantly to the country's pollution problems. In order to curb emissions and keep a tap on its pollutants, China has developed a short-term plan to decrease its coal dependency to 65% of current levels by 2017 (See Figure 5).

By lowering its dependency on coal, China is stretching its non-coal energy resources, especially other hydrocarbons, to make up the shortfall from coal energy.

Currently, nearly 81% of Chinese hydrocarbon production capacity is located onshore, while the remaining 19% of production is contributed by shallow offshore reserves. China has also opened doors to IOCs to explore and produce oil and gas in offshore and challenging hydrocarbon fields. In 2013, China invested $13 billion on exploration to help compensate for its reduced reliance on coal as a fuel.

All these factors have squeezed China and have resulted in China pushing its borders to look for oil and gas in areas like the East China Sea and South China Sea, both of which have resulted in territorial disputes with neighboring countries, including Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

JAPAN'S ENERGY REQUIREMENT

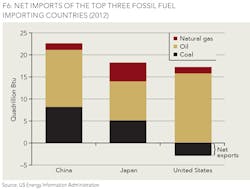

Japan is the third-largest net importer of oil after China and the USA, is the second-largest importer of coal, and is the largest importer of LNG products. Japan is an economic powerhouse and needs massive amounts of energy imports to sustain its economy because it has very few domestic sources of energy - at least none that are being widely exploited. Japan produces less than 15% of its energy requirements from within its borders, making the nation almost entirely dependent on imports (Figure 6).

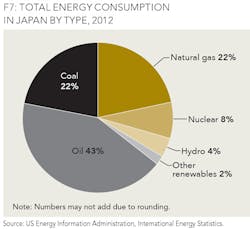

Prior to 2011, nuclear energy contributed nearly 26% of Japan's energy needs. But in March of that year, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake off the northeast coast of Honshu resulted in a tsunami that inundated Japan's shore and triggered the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Post this catastrophe, Japan lost almost all its nuclear energy for a time. However, in recent days, Japan has resumed operations at some of its nuclear power-generation plants (Figure 7).

Japan's energy bill for imported hydrocarbons has swelled to approximately $250 billion, resulting in a trade deficit that is adversely affecting its economy. Energy consumption remains high, but with a major chunk of energy being taken off-grid after the Fukushima tragedy, Japan is desperately searching for available energy in places such as the East China Sea as it watches its energy deficit soar.

EAST CHINA SEA

The East China Sea or Tung Hai (literally meaning Eastern Sea in Chinese) lies in between the coastal states of China and Japan and its limits are defined in the Limit of Oceans and Seas, 3rd Edition, 1953, International Hydrographic Organization.

EAST CHINA SEA HYDROCARBONS

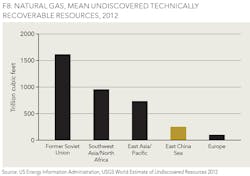

Due to the contentious nature of the dispute over territorial claims in the East China Sea, there has been very limited seismic activity in this region. It has been estimated that East China has reserves from 60 million to 100 million barrels of crude oil. That extent of reserves, though, does not make the East China Sea an attractive investment and thus a point of contention for China and Japan. But it is the gas reserves which have the potential to make one of these super economies virtually independent of costly hydrocarbon imports. There have been an estimated 1 to 2 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas underlying in the East China Sea. That significant volume of gas reserves is enough for any nation to maliciously push its boundary limits and claim sovereignty over the reservoir (See Figure 8).

EAST CHINA SEA DISPUTE

While chalking out the boundaries and determining sovereignty over the disputed territory (See Figure 9 map), three main factors should be noted:

- Treaties

- Historical boundaries (uti possidetis juris)

- Effective control (effectivités)

The main dispute between China and Japan revolves around Daiyou (Chinese Name) or Senkaku (Japanese Name) Island which consist of three barren rocks and five uninhabited islets. Both countries have laid their claim to these islands, which cover roughly 81,000 square miles.

The root cause of the dispute dates back to the nineteenth century Sino-Japan war. China asserts that Daiyou/Senkaku Islands were part of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan while Japan has contested this assertion vigorously. Japan ceded control of Taiwan, which the Japanese called Formosa, to Mainland China after the defeat of the Japanese Empire in World War II but without mentioning anything specific about these islands. Thereafter, no party challenged the sovereignty claim of the other until 1969 when UN CCOP estimated huge hydrocarbon deposits near the Daioyu/Senkaku islands.

China claimed disputed land based on its historic use as navigational assistance. The Chinese government also iterates that Japan ceded this territory to China as part of 1895 Shimonoseki Peace Treaty.

Japan disputes this claim and asserts sovereignty over these islands as vacant territory (terra nullius). Japan also proclaims that it administered these islands as part of Nansei Shoto. This makes administration of these islands separate from Taiwan and the Shimonoseki treaty. Japan further mentions the lack of Chinese demands to this territory prior to 1970 as validation to its claim.

CHINA'S CLAIM TO THE EAST CHINA SEA

China's claim to the East China Sea is based on UNCLOS article 76(1). China asserts that the disputed territory falls within the outer edge of the natural prolongation of its continental shelf. China's foreign ministry has issued a statement saying in part, "The natural prolongation of the continental shelf of China in the East China Sea extends to the Okinawa Trough and beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of China is measured."

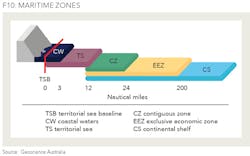

Henceforth, China submitted its evidence of natural prolongation of its continental shelf to the commission on 14th December 2012 as per article 76(8) of UNCLOS (See Figure 10).

JAPAN'S CLAIM TO THE EAST CHINA SEA

Japan, too, has claimed sovereignty over the disputed territory using the same UNCLOS. The government in Tokyo claims that Japan has a sovereign claim over the Daiyou/Senkaku Islands and that disputed areas fall within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), as per Article 57. However, as per Article 121(3), rocks do not extend an EEZ or continental shelf.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

China has disputed the boundaries of the East China Sea ever since the Okinawa Reversion Treaty in 1972. Chinese interest in the disputed area was ignited by the discovery of hydrocarbons in 1969. Since then China and Japan have each accused the other of violating its territorial sovereignty. Beginning in 2004, both economic giants agreed to conduct bilateral talks to resolve the dispute. The Chinese foreign minister said, "We are willing to work with the Japanese side to push forward bilateral relations." However, there was no significant development till 2008, although Japan had intermittently criticized China of exploiting hydrocarbon reserves in the disputed area. Finally, a breakthrough was reached in 2008 when both parties agreed in principle to explore and exploit four East China Sea fields jointly and halt all activities in the contested areas. At the time, this was hailed as a sign of greater cooperation in the long-standing dispute.

Japan's 1996 Law on the EEZ and the Continental Shelf further diffused the situation. Japan said it was open to have an equidistant line separating its territory from China's. However, China refused to recognize the demarcation of the East China Sea, and the previous cooperation between the two parties disintegrated. Increased tension between China and Japan was exacerbated in 2008 when a Taiwanese vessel rammed into a Japanese patrol boat. This event fueled mass discomfort by the Chinese who see Japan as an assailant to Chinese sovereignty.

Both countries are signatories to the United Nations Charter and have an obligation to abide by Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, which they have been ignoring in the dispute. China launched its first aircraft carrier in 2012 "to effectively protect national sovereignty, security, and development interests." While Japan responded with its first increase in defense spending in 11 years. Japan also began providing military aid to some of its regional allies in the area.

China, on the other hand, has declared an Air Defence Identification Zone over the East China Sea. All these events are pointing to a head-on collision between China and Japan and an arms race, which could threaten world peace.

POSSIBLE WAYS TO A PEACEFUL SOLUTION

According to Article 2(3) of the UN Charter, both parties have an obligation to resolve their border disputes peacefully and amicably. The charter further emphasizes in Article 2(4) on refraining from the use of force to resolve disputes and underlines the need for "negotiation, inquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice" as per article 33(1).

History tells us that bilateral talks and negotiations are the best way to resolve border disputes. This usually results in a treaty that becomes a source for boundary demarcation and any potential future disputes. The attractiveness to this method is that both parties reach a solution cordially and thus do not leave a bad taste as neither party feels pushed to the solution. The Sino-Soviet agreement of 1991 and Vertrag von Shimoda, entered into by Japan and Russia in 1895, are examples border disputes being resolved by bilateral talks and agreements by China and Japan with a third party. Unfortunately, negotiations with respect to the East China Sea thus far have not been successful. There has been a general reluctance by both parties to press on with the solution since negotiations began 10 years ago.

Another method has been mediation and conciliation, although this avenue sometimes the mediation body's decision is viewed as forced and parties tend to reject the findings, as was the case in the Maroua Declaration between Cameroon and Nigeria.

The mediation body can be either religious or ethnic, as was the case in Act of Montevideo in 1979, or an independent entity, as in the example of a dispute between Chile and Peru, which was mediated by the United States.

Using mediation or conciliation as an option for the East China Sea dispute does not seem practical because there is little common ground between the disputants. Similarly, an independent entity like the US or the UK cannot be taken as a mediator because of the 1952 Anko Joyaku treaty. China is also a permanent member on UN Security Council and has grown in global political stature in recent times, so there is a high probability that China would reject all kinds of mediation or conciliation.

If a collaborative means of dispute resolution fails, that leaves either arbitration or judicial settlement as the only peaceful resolution to the East China Sea dispute. The Philippines has already adopted this route and has taken China to international arbitration over their demarcation dispute in the South China Sea. However, the case has not progressed because China has declined to participate thus far.

UNCLOS RULING

Japan's claim to the East China Sea indeed has merit. Japan claims the disputed islands of Daioyu/Senkaku and its associated EEZ, which it has administered as part of terra nullius. Japan cites uti possidetis juris and effectivités to assert sovereignty over these uninhabited islands.

The historical context of Japanese administration over the islands can be verified by the fishery permit applied by a resident of Okinawa Prefecture back in 1894. After the defeat of the Japanese Empire in World War II, Japan ceded control of Taiwan to China but did not specifically include mention about the control over the Daioyu/Senkaku islands as part of the Shimonoseki Treaty. Also as per Article 3 of the subsequent 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, these islands fell under the administration of the United States for a time, and later Japan resumed administration over the islands as part of the Nansei Shoto Islands, post Okinawa Reversion Treaty. All these facts reinforce Japan's claim to sovereignty over these five islands.

China, too, claims historical context to these islands and asserts that they were part of China during the Qing and Ming Dynasties and were taken over by Japan after the 1895 Sino-Japan War. As per Article 8 of the Potsdam Declaration, "Japanese sovereignty [was] limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands." China cites this declaration as evidence that the islands were ceded by Japan to China at the end of World War II along with Taiwan. Consequently, China claims sovereignty over the islands and the EEZ as per uti possidetis juris. It further stresses that the disputed area falls within the natural prolongation of its continental shelf, which makes a compelling argument by China.

However, a concrete Chinese claim to these islands dates back only to the Okinawa Reversion Treaty in 1972 when hydrocarbons were discovered in the East China Sea. Previously, China had not expressed any objection either to Japanese control or US control in the years after World War II. This is evidence that China is only interested in the hydrocarbon deposits in the area. The absence of China from the arbitration proceeding with the Philippines over their dispute in the South China Sea tends to reinforce the view that China's interest in the islands is purely economic.

EQUIDISTANCE AND JOINT OPERATIONS

Article 15 of UNCLOS advocates equidistance in the event of two opposite coastal states, as is the case in the East China Sea dispute between China and Japan. It further instructs that such arrangements have to be made effective as per Articles 73 and 84. While equidistance is the initial point for delimitation, there can be a general exception as was the case in the Nicaragua-Honduras and Gulf of Maine cases where a bisector method was used in the absence of baseline identification. Furthermore, UNCLOS 74(3) and 83(3) allow disputants to "make every effort to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature during this transitional period" in order not to stall any economic development in the disputed areas. Joint development agreements are generally a temporary arrangement in such disputes, as was the case in Guyana-Suriname.

Looking at the Japan-China dispute, Japan did propose an equidistance line, which was rejected by China. In 2008, both parties agreed to jointly explore four East China Sea hydrocarbon fields, but that was met with the Minjinyu 5179 Incident that triggered a war of words between the two rivals. Since then, prospects for resolving the dispute have been bleak.

In a situation such as this, where both Japan and China are in a regal tussle not to recognize each other's territorial claims, joint operations are not a viable option. Similar examples are the territorial disputes between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia's Neutral Zone and between Eritrea and Yemen and in controversies involving the North Sea continental shelf. The ICJ ruled that "an equal division of the overlapping areas or by agreements for joint exploitation" will be the best way forward to economically extract the underground riches.

BENEFITS OF JOINT OPERATIONS

There are many benefits for both China and Japan by jointly undertaking the exploitation of East China Sea by either NOCs or IOCs due to:

- The infrastructure required to develop East China Sea reservoirs would be very capital intensive due to the intense logistics and the geography of the area. By undertaking joint operations, both parties would reap the benefits of reduced investment exposure. Japan is already facing a huge trade deficit, and by undertaking development jointly, Japan would reduce its exposure to capital investment.

- The East China Sea has an average depth of 349 meters (about 1145 feet). The exploitation of oil and gas reserves at such depth would require expertise in both sea drilling and pipeline laying. Joint ventures would combine the scientific knowledge and expertise of both countries.

- At present, both countries depend on fuels that are inherently pollutants - coal in the case of China and nuclear in case of Japan. If the two countries were to work together in the East China Sea, both would reduce their dependency on these fuels and diversify their domestic energy consumption.

- China and Japan, as we stated previously, are two of the world's top three oil importers (along with the United States). Resources in the East China Sea could help both nations reduce energy imports and put them on the road to a self-sustaining economy.

- China and Japan have been traditional rivals. Undertaking a joint venture of this magnitude would enable them to reduce defense spending and would provide substantial employment opportunities for both countries. Working together shoulder to shoulder would allow for greater harmony to develop between the Chinese and Japanese populations.

- Finally, China and Japan are both among the world's great economic powerhouses. The trade volume between them is worth billions. Both countries export and import from each other. Mutual trade will grow only if neither country is adversely impacted by not having sufficient domestic energy.

CONCLUSION

China and Japan have locked horns for a long time. Neither is showing any flexibility in their dispute over hydrocarbon assets in the East China Sea. There are compelling arguments on both sides. However, it is crucial that these neighbors settle their argument in order to deescalate the situation and avoid a potential military conflict. It is high time that China and Japan put their legacy differences aside and try to find solution.

With its mammoth reserves, the East China Sea has the potential to reverse the negative impact petroleum imports are having on the fiscal budgets of both countries. These traditional rivals need to show flexibility and strive to find a solution along the same lines as the countries involved did over the North Sea continental shelf demarcation lines. The benefits of such an arrangement would be far reaching.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Muhammad Waqas is a mechanical engineer currently pursuing a degree in energy law. He resides in the United Arab Emirates where he has gained experience in the oil and gas sector. His areas of expertise include energy politics in the Middle East and elsewhere.