Is Iran worth the risk?

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT THE IPC AND THE 2016 LICENSING ROUND

SYD NEJAD, NAFT ENERGY INC., CALGARY

MORE THAN 80% of known hydrocarbon reserves worldwide are controlled by state oil companies. To satisfy shareholders and keep the reserves life index (RLI) high, international oil companies (IOCs) and independents have to diversify their portfolios with unconventional assets, which naturally demands bringing in a mix of barrels with higher capital intensity, finding and development costs (F&D), and operational expenditures.

Iran's low capital expenditures (Capex) and operational expenditures (Opex) barrels are deemed to be a relief in the current low price environment for those who dare the above-surface risk of the country.

IRANIAN OIL & GAS FIELDS

Today more than 70% of Iran's crude production comes from fields with 50 years and more life. Major investment is needed to offset the 8% to 10% decline in Iran's 3.2 million barrel crude production per day and turn the curve upward.

The National Iranian Oil Company's (NIOC's) estimation of the cost of Iran's barrels is about $8 to $10 per barrel. Our analysis suggests that F&D plus Opex of Iranian fields can have a range of $8.0 to $16.0 per barrel of reserve.

A quick review of Iranian projects developed from 1995 to 2005 indicates that the capital-intensity of greenfield onshore projects in Iran was around $10,000 to $15,000 per flowing-barrel. Accounting for 3% annual inflation between 2000 and 2015, this is about a third of the same for unconventional fields in North America.

IRAN PETROLEUM CONTRACT (IPC)

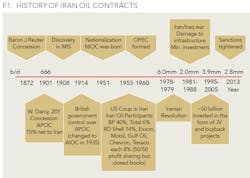

Iran has a long history of oil contracts (Figure 1). First oil started in 1901 under a concession that later turned into a production sharing contract (PSC) in 1951. The latter went through revisions until the Iranian revolution in 1978 when the right of producing and owning natural resources, including oil and gas, was given to the new Iranian government on behalf of Iranians. Booking reserves by IOCs is still one of the red-lines set by the Iranian constitution.

Lately, Generation Three of her technical contracts (famous in Iran as buy-back contracts) attracted about $50 billion between1995 and 2005 until nearly all investors flew away when the sanction pressures increased between 2010 and 2014.

Under the buy-back contracts a joint master development plan (MDP) was prepared, parties agreed on a ceiling of Capex investment, a cost-recovery period was negotiated, and a fixed ROR was agreed upon. IOCs provided all the Capex and developed the field. The spent Capex was treated as a loan to the state, which then produced annuity payments from the onset of production (or the achievement of the production target) until the end of the contract term. Through payments, the IOCs recovered their capital expenditures, operating expenditures, and bank charges accrued during the development phase. The IOCs could be paid in kind. The development phase usually was two to four years, and the production phase was about five to 10 years.

Although NIOC's buy-back format was not the best of technical-service contracts, but the 15% to 18% rate of return on investment was attractive enough to engage several IOCs in the 1990s and the first few years of the new century.

The Iran Petroleum Contract (IPC) is the latest product of NIOC and is being promoted as a hybrid oil contract, as it is not a PSC but tries to include some of its advantages. Booking of reserves will still be a red-line but several shortfalls of the buy-backs seem to have been addressed (See Table 1).

At the 2016 IPC licensing round, IOCs will bid coefficients for different aspects of the development plan, including but not limited to minimum contractual work commitment, production plateau, unit Opex, fee per barrel, and the speed of cost recovery. A matrix will calculate each bidder's score. Other factors that come into the play are the complexity factor (e.g. development vs. EOR), and geological possibility of success (POS) in the case of exploration blocks. Sounds complicated, but with the transparency that NIOC has promised not a mission impossible.

Technology transfer and building local capacities are among the strategic objectives of the IPC. To serve this purpose, the IPC has a tiered base remuneration system that allows increase of the fees to the IOC on each produced barrel if the target is overachieved. The model is designed to encourage IOCs to deploy the latest technological advancements in the domain of reservoir management, optimization, and production.

WHAT WILL BE THE IPC'S FOCUS?

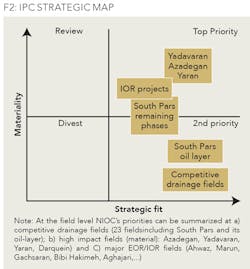

Iran's goal is to attract $180 billion to its upstream oil and gas industry and boost crude production to 5.7 MMb/d by 2020. NIOC is aiming for about 1.0 MMb/d production boost through the upcoming 2016 IPC licensing round, of which 150,000 b/d is expected to come from competitive drainage fields (23 onshore and offshore fields), about 300,000 from improved oil recovery projects (IOR), and about 550,000 b/d from major fields discovered over past two decades (Figure 2). The final list of the projects is expected to be announced at a summit in London in February 2016. The first IPC licensing round is expected to start in the second quarter of 2016.

In view of the volume of the work that NIOC needs to handle in a short period of time, the IPC licensing bid is likely to be held in two or three rounds. With regard to the country's need for cash-flow, most of the exploration blocks are expected to be postponed while IOR projects of major fields, which were not in the initial lists (distributed by NIOC in 2014), are expected to show up in the first round.

The technology goals of the NIOC are summarized as follows:

- IOR/EOR-related technology: high-tech basin and reservoir modeling, hi-res seismic interpretation, reservoir characterization, waterflood schemes, gas injection, hydraulic fracturing, reservoir management, and optimization;

- Sour gas handling know-how and hardware, particularly for the South Pars field;

- Small-scale LNG and GTL technologies;

- Exploration for gas and gas monetization onshore to support growing domestic demand and serve/expand regional export contracts; and

- Exploration in the Persian Gulf - a low priority, but needed as the NOC lacks extensive exploration expertise, especially offshore.

The deepwater Caspian Sea and regional shale are unlikely to be in the short to medium scope of the NIOC.

IRAN'S RISK PROFILE

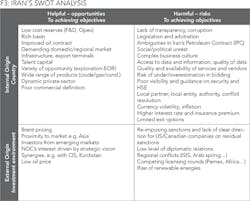

The Middle East in general is not an investment heaven, and Iran is no exception. Ongoing conflicts with Saudi Arabia and Israel and anti-west political views of the leadership drags Iran's investment score down. Business Monitor International (BMI) research awarded a score of 28.1 out of 100 for Iran's Trade and Investment Risk. This places it in the fourth-highest risk position regionally out of 18 countries. Higher country risk translates into higher insurance rates and higher costs of capital, and this while the country carries a dual-exchange rate system and a double-digit inflation rate. Legislations and jurisdictions are well defined and documented, but at the time of execution one notices how interpretive they can be (Figure 3).

The business community and private sector in Iran have a long history of trade with international companies, but mostly in the agency and dealership format. Long-lasting, win-win business relationships through JVs and partnerships have not been common.

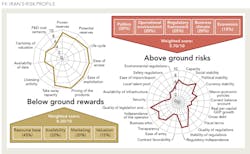

Our analysis rates Iran's above-ground risk at 5.7 (in a zero to 10 scale where the higher score means higher risk), and the country's below-ground rewards at 8.2 point basis, where the higher number means higher reward (Figure 4).

MARKET IMPACT

Iran's petroleum minister repeatedly has emphasized that Iran will open up despite the current low-price environment. Thanks to the low-cost barrels that enable the country and the investors to make reasonable margins even at $40 to $50 per barrel crude prices. Some market analysts believe that the current low-price environment already takes into account the negative psychology of Iranian crude hitting the market in the first quarter of 2016, post implementation of the JCPOA, however it is hard to estimate the extent of the impact this will have on pricing.

Historically, OPEC has internally absorbed the production boost of its members and has committed to its overall budget. However, the cartel's recent strategy to secure market share may suggest that Iran's production boost would not be absorbed by its members, but used as a stronger push against further development of unconventional resources.

WHO MIGHT BID?

Majors and super-majors offer a package deal. They will bring Iran the technology, financial strength, political stability, and organizational capacities. Majors also have higher tolerance and more experience with risk profiles in markets such as Iran. Total, Eni, Shell, Lukoil, OMV, Petronas, and ONGC are already in conversations with NIOC. We do not expect US-based E&Ps to participate in IPC licensing rounds, at least not in the first round. The next milestone for US oil and gas companies is the November 2016 presidential election.

Mid-cap E&P companies were engaged at the time of buy-backs and are expected to show up again. They may not bring a heavyweight political tie with their respective governments, but if they demonstrate their competitive advantage and target a niche, they would have a good chance in securing below 50,000 b/d assets (of which there are many on the IPC project list).

There are a few small- to medium-sized E&Ps with success stories in places such as Kurdistan and Oman that could expand on synergies in the region by participating in the licensing rounds. Maersk has an operation on the Qatari side of the South Pars, and DNO's experience in Kurdistan and Oman are good examples. Mid-caps with prior experience in emerging markets have fewer concerns with Iran's risk profile.

Start-ups will not meet NIOC's prequalification cut-offs. However, juniors may have a chance if they start early and build the relationship, showcase unique competencies, and target a field that is a good fit. The success CCED' has seen in its exploration program of Oman's Blocks 3 and 4, as well as its ability to set up the early-production system nine months after its discovery is a bright regional example.

We have observed the successful execution of start-ups and small-cap E&P operators into emerging markets such as Oman, Kurdistan, Angola, Kenya, and Mozambique in the past decade. Crafting of an entry strategy, diligent planning, and early engagement are keys to a successful engagement into the 2016 IPC licensing round, in particular for small-cap companies.

In addition to E&Ps, oilfield service companies have a chance for success in the upcoming IPC round. After all, technical-service contracts fit them the best. We expect Schlumberger to participate given the company's extensive data and information from Iranian fields and the operational footprint SLB already has in Iran. Other major oilfield service companies may pick a safer entry strategy and choose to sell products and services at first, at least until the US presidential election is over.

HOW TO ENGAGE

Investors targeting emerging markets expect higher rates of return, but should also mind higher risk of such markets. Often oil and gas is the only (or major) source of income for the state, so the native industry is usually highly political, which adds to the risk and complexity of entry, and later, on running the business.

Participation in the 2016 IPC licensing round should not be treated similar to bidding for a license in the Norwegian Continental Shelf or the Gulf of Mexico. One cannot afford to show up right at the opening, purchase the bid packages, bid, and hope for the best. Understanding the business culture in Iran and learning and appreciating local values is a good place to start. Furthermore, IOCs should get to know NIOC, its concerns, objectives, and goals.

A thorough planning, meeting with stakeholders, and understanding of market dynamics, coupled with the development of an engagement plan is vital. Creditors and shareholders will have a higher appreciation if IOCs do their homework and have an entry strategy and risk mitigation plan in place before taking part in the bid round.

CONCLUSION

Iran's oil and gas renaissance might be bad news for E&Ps in general, but not necessarily for the ones taking advantage of the opportunity and attempting to balance portfolios by adding in some low-cost barrels. Like entering into any emerging market, crafting an entry strategy and proper risk mitigation plan is a must.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Syd Nejad is CEO and managing partner of Calgary-based NAFT Energy Inc. He has a wealth of international experience in upstream projects in such markets as Oman, Pakistan, Iran, the UAE, Yemen, and Tunisia. He has worked in a variety of roles, including strategy and corporate planning, acquisition and divestiture, portfolio optimization, asset management, production/field operations, and reserves and reservoir/exploitation engineering. At NAFT, Nejad leads investment and engagement in oil and gas projects in emerging markets. Prior to NAFT, Nejad worked for Statoil Canada, Husky Energy, Weatherford, Baker Hughes, and Schlumberger.